OLD FASHIONED PHARMACY

by

GEORGE ROBERTSON, FSAScot.

Nowadays, when in need of some form of medication, we make our way to the doctor’s surgery where we are given a prescription for the appropriate tablet or, if we feel confident enough to deal with the matter personally, we visit the local pharmacy, where some appropriate item can be purchased over the counter without prescription. There is no doubt the National Health Service, which commenced in Scotland on 5th July, 1948, under the National Health Service (Scotland) Act, 1947, has been to our great advantage and has helped to improve the health of ourselves – and of the nation. This obviously did not apply during earlier times when people were left very much to their own devices to treat ailments and once again we turn to Alexander Stewart’s book Reminiscences of Dunfermline – Sixty Years Ago, in which we are given an idea of some of the home remedies our forebears were required to use – and a sight of some of the people who administered these remedies.

Stewart recalls the names of medicines that used to be prescribed for ailments and diseases in those early days –

“For pleurisy, take half a drachm (eighth of an ounce) of soot: for nettle rash, rub the parts with parsley; for gout, apply lean raw beef; for a cut, bind on it toasted cheese or pounded grass; for asthma, live for a fortnight on boiled carrots only; for dropsy (watery fluid collecting in the cavities or tissues of the body), use a tea made from broom. When young infants cried, apparently from some inward spasms, we have seen anxious mothers take out of the fire one or two red hot cinders and put them into a cup of water, and give the child a teaspoonful or two of that. For dysentery, a lump of alum (hydrated double sulphate of aluminium and potassium) to be carried in the pocket; bronchitis, goose grease and treacle; smallpox, sheep’s tongue boiled in milk; cramp, the knuckle bone of a leg of mutton to be carried in the pocket; rheumatism, the garters to be worn filled with sulphur. It was not from a superstitious feeling that an old friend of the writer’s (Stewart) carried about with him in his pocket a raw potato; he was firmly convinced that it relieved him from rheumatism, with which he was sometimes afflicted. “Flannel and patience” were also considered of great service in the case of those suffering under this severe ailment. Rubbing with swine’s seam (pigs fat), and also with ointments of fresh butter and soot, was very often recommended.”

After describing the treatment for these various ailments, Stewart then goes on to tell us about some of the people who were considered experts in administering these treatments –

“Some old people, who made pharmacy a speciality or hobby, were reputed to be what was termed very skilly (clever or skilful) in the art of curing diseases, and in almost every town and village such persons were to be found. Some of them became noted for their skill and the cures they performed, and patients would sometimes travel long distances to consult them. Dunfermline had its quota of such amateur professionals – its Mrs M’Gorams and its Sarah Wilsons, with their healing herbs, celebrated “saws” or ointments, to whom many resorted for advice. Even the most enlightened and the best educated medical men of only sixty years ago used to bleed or blister their patients for almost every ailment! If they did not blister or bleed, they were neglecting their duty, and were considered unsafe and unworthy of confidence – in short, unfit for their work. Some country people were in the regular habit of going to some apothecary or other twice a year to be “blooded,” as it was called, in order to prevent trouble coming upon them. They were often bled till they fainted: the usual charge for this was one shilling. Epsom and Glauber salts (used to empty the bowel), aloes, calomel, senna, jalap, Castille soap, magnesia, and cream of tartar were held in high repute and universally recommended.

“Those who usurped the domain of the college bred medical man – and their name was legion – invariably prescribed very homely remedies. Some prescribed the application of “moose wabs” (cobwebs) for sores, and also pills of the same to be taken internally. There was also decoctions of herbs and poultices of horse and cow dung. Marigold tea was usually given to children suffering from the “nirles” (measles); and the holding of a child over the mouth of a coal-pit was resorted to as a change of air for relieving “kingcost” (hooping-cough). For those who were troubled with warts, the rubbing of those excrescences with the fasting spittle – the first thing in the morning – was prescribed; or, what was considered better and more highly recommended was to steal a piece of butcher meat, rub the warts with it, then bury the meat in the ground, all without the knowledge of anyone, and as the meat decayed so would the warts. The writer (Stewart) has frequently seen boys anointing the warts with the white milky juice exuding from the stems of dandelion flowers. No doubt there is acid in this, as well as in the fasting spittle.

“The druggists of those days, such as Charles Macara on the Bridge (Bridge Street), and Dr Cameron, did an extensive business in the way of giving medical advice and in practising surgery in their back shops in cases of illness. It was the practise all over the country for those who kept apothecary shops to do a good deal in simple cases requiring medical and surgical treatment. At a former time the barbers did the bleeding business. There is a story told about one of those druggists in the west part of the country. A poor woman had a sick child, which she took to him for advice. She was recommended by him to put the child into a black sheep-skin newly taken from the animal, and let it remain in that all night! This was faithfully attended to, but the child died before morning. She afterwards told the druggist her sorrowful tale with all minuteness; but he told her she had “used the best means in her power,” and to “go home and get the child buried,” and he would not charge her anything for the cure he gave!

“In cases of fever the putting of a patient into a sheep-skin, while the feet were well saturated with new milk, to draw the fever down, was very frequently adopted.

“Pharmacy has made wonderful progress during the last fifty or sixty years. Like all other sciences, it is still making extraordinary advances, which all tend to the alleviation of human suffering. In old times we had no chloroform, with its soothing and blessed influence, in cases of severe surgical operations. We had no infinitesimal, tasteless, homeopathic doses of medicine, but the very reverse; nor had we the stately hydropathic palaces we see on all hands. There were no public analysts to test our food and our drink, such as we have now in our towns and cities. Water in many towns and villages was often very impure and most unwholesome, and was the cause of diseases of which we now hear almost nothing. But then our ears were not dinned (by constant repetition), as they are now, about the deadly germs which are floating in the air around us, in the food we eat, and in the water we drink. It appears that we cannot possibly go where germs are not. They abound everywhere, and much to our discomfort. Little did we know the milk which had got “blinket”, or turned, was in consequence of the pranks of those germs we now hear so much about; but of all this we then lived in blissful ignorance.” (1)

Stewart gives us a wonderful insight into medicines used in Dunfermline during the early part of the 19th century but we are also fortunate in the fact he also mentions some of those by name who were treating the invalids of the town during that time. He makes mention of Mrs M’Goram (see Notes) and Sarah Wilson, but unfortunately nothing further is known of the women. However, this is not the case with the other two he mentions, these being Charles Macara and Doctor Cameron, both of whom are mentioned in the 1835 Dunfermline Almanac and Register, Macara being recorded as a Druggist and Seedsman, with premises at 18 Bridge Street. Macara died, aged 45 years, on 11/11/1839, and is buried in Dunfermline Abbey Churchyard. (2)

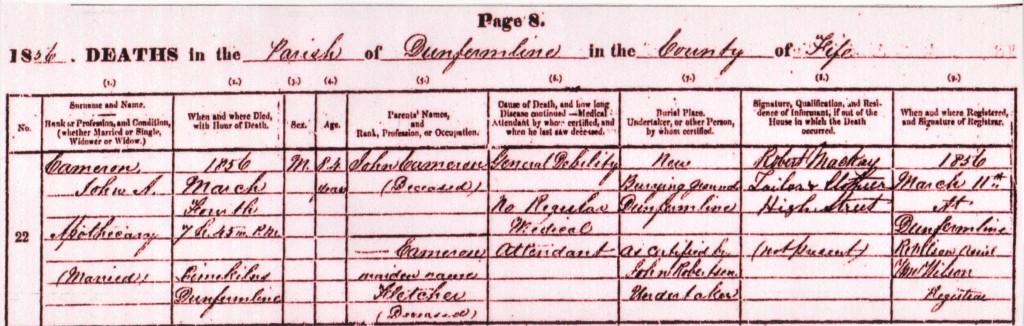

Doctor Cameron is shown in said Almanac and Register to be a Druggist with premises at 21 High Street and he is next found in the 1841 census for Dunfermline, living at High Street, with his wife Elizabeth. He gives his name as John Alexander Cameron, is 58 years of age and gives his occupation as Surgeon. The 1851 census for Dunfermline shows Cameron to be living at 14 High Street with his wife Elizabeth. He is shown to be 67 years of age, born in Inveraray, Argyllshire and still describing himself as a Surgeon. (3)

Once again we turn to Alexander Stewart’s Reminiscences of Dunfermline – Sixty Years Ago, where we find an interesting description of Doctor Cameron. Stewart tells us Cameron was one of the doctors who administered to the people of Dunfermline when cholera struck the town during 1832 and again during 1849. Stewart says Cameron was one of the “characters” of the town where he was familiarly called Doctor “Hollipotts” and goes on to give the following description of him.

“He was an old Highlandman, was kindly and genial in his way, and had seen active service as a surgeon in a Highland regiment. His skull had been fractured by a sabre cut or gunshot wound, and I have seen him show where it had been clasped by a silver clasp. He used often to walk up and down in front of his shop door, always prim and starched, wearing an old-fashioned high ruffled collar, and was always dressed in black suit and white neck-cloth, and had his gold-mounted cane in his hand.” (4)

Yet another description of Dr Cameron is provided by Daniel Thomson in Volume 1 of his Anent Dunfermline, who tells us – “This somewhat notable man was long known in Dunfermline as the ‘Daft Doctor’. He was a native of Argyllshire and proud of his Highland descent. He received elements of his education in the parochial school of Inveraray. He went to college (University of Edinburgh?) – Thomson’s brackets and question mark – and in due time took his Diploma as an M.D. He joined the 79th Regiment and remained in the army for about six years. He commenced business in Dunfermline about 1825 as a Druggist and Chemist having a small, dark and mysterious looking shop at the lower end of the High Street, north side. He was understood to be adept in the cure of sexual diseases and those who had troubles of this sort were always recommended to the ‘Daft Doctor’. He married about 1796, but never had any family. He was a kind husband and an obliging friend but he had a clansman’s bitterness and hatred to those who offended him. He died at Limekilns in 1856. He left a widow of 80, and an old servant, also about 80 years. Contributions in their support were taken in the town by Messrs Stewart, Grocer and Mackay, Tailor, High Street.” (5)

With regards, the contributions being sought in Dunfermline for Dr Cameron’s widow and servant, in a later entry in his Anent Dunfermline Thomson tells us this did take place and the sum of £2:10/- was collected and, in addition – “numerous friends contributed their mite in help of the two octogenarians.” (6)

What are we to make of the so called Dr Cameron? He was, to say the least, quite a character but the question is – was he a fully qualified Surgeon or Doctor? The census of 1841 and 1851 record him as a Surgeon and Stewart and Thomson both describe him as a Doctor, but add the nickname of Dr “Hollipotts” and the “Daft Doctor”! We know he had business premises on the High Street, he being described as a Druggist and, on his death certificate, he is recorded as being an Apothecary. However, enquiries at the Royal College of Surgeons, Edinburgh and the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons, Glasgow revealed there is no record of a student named John Alexander Cameron having attended either. It is the view of this writer that until further evidence is forthcoming, it is perhaps the wisest course to assume Cameron was not a qualified Surgeon or Doctor but was in fact a Druggist or an Apothecary.

It is obvious those requiring medical assistance in those days had great faith in the so-called doctors who were prepared to treat their ailments. Treatment and types of medication was, to say the least, basic and very much trial and error. When comparing the standards of health care we enjoy these days to what was experienced or even endured, all those years ago, we might consider ourselves extremely lucky. However, despite great advances, old treatments can still be heard of today. Stewart comments on parsley being rubbed on nettle rash but who remembers being advised to rub the sting with a docken leaf – or perhaps still believes in using this remedy. Stewart also mentions poultices of the horse and cow dung variety but those of us of a certain vintage might remember a poultice being applied to an infected finger although, thankfully, the latter was of the bread poultice variety, not the horse and cow dung version! Another type of poultice still in use today is the mustard poultice or pack, placed on the chest to alleviate the effects of a cold or cough, surely another example of an old treatment still in use today. However, this writer is at a loss to draw modern comparisons with other old treatments such as sulphur being placed in the garter as treatment for rheumatism, or, for asthma, living on boiled carrots – and nothing else – for two weeks and finally, being bled until the patient fainted – and being charged one shilling for the privilege!

References, Notes and Acknowledgements

- Reminiscences of Dunfermline – Sixty Years Ago by Alexander Stewart, pub. 1886 by Scott & Ferguson & J. Menzies & Co., Edinburgh, also by Simpkin, Marshall & Co., London, pp46-49.

- Fife Herald Newspaper, dated 28th November, 1839, p.3

- Census for Dunfermline for 1841 & 1851.

- Reminiscences of Dunfermline – Sixty Years Ago by Alexander Stewart, pub. 1886 by Scott & Ferguson & J. Menzies & Co., Edinburgh, also by Simpkin, Marshall & Co., London, p167.

- Anent Dunfermline by Daniel Thomson, Vol., 1, Item 94.

- Anent Dunfermline by Daniel Thomson, Vol., 1, Item 111.

It will be noted Thomson, in his Anent Dunfermline, states Dr Cameron’s shop was situated at the lower (west) end of the High Street, north side, giving the street number of the shop as 21. This was the numbering system at that time. Today the properties on the north side of High Street are given even numbers whilst those on the south side of the street are given odd numbers, this reversal of numbers taking place during the late 1860’s or early 1870’s.

With regards to the Mrs McGoram mentioned by Stewart in his Reminiscences book, a possible candidate for this person might be Agnes Beveridge or McGoram, (1775-1865), who resided at Brucefield Feus, Dunfermline and is shown in the Dunfermline census’ of 1841, 1851 and 1861, to be a dairy woman. According to Ancestry.co.uk, Agnes married a 48 year old Irishman named Peter McGoram (sometimes McGorum) at Dunfermline on 15th November, 1792, Agnes being 18 years old, the couple going on to have two sons, John and Edward. Since Agnes and Peter appear to be the progenitors of the McGoram name in Dunfermline, it is highly likely Stewart’s Mrs McGoram would be Agnes or perhaps one of the wives of her sons. However, it should be emphasised this identification of Mrs McGoram is mere conjecture on the part of this writer and has not been proved conclusively.

The image of John Alexander Cameron’s death certificate is reproduced here courtesy of the National Records of Scotland, per Statutory Death Records of Dunfermline, Register number 424/2/22.

Alexander Taylor’s photograph of the west end of High Street, showing the soon to be demolished Town House, was taken during 1876, just prior to demolition taking place. Alexander Taylor, full name Alexander Pearson Taylor (1824-1892), operated his photographic studio at that time (1876) from I East Port, Dunfermline, having moved there from an earlier studio in Kirkgate. The photograph is reproduced here courtesy of OnFife Archives (Dunfermline Local Studies) on behalf of Fife Council.

Once again, I am indebted to Sharron McColl of Dunfermline Carnegie Library and Galleries, who was of great assistance to me whilst researching this article.