By Dr Jean Barclay

My Edinburgh City Plan of 1978, like so many plans, maps and atlases, was created by John Bartholomew and Son, Ltd; a family company that loomed large in the business of map-making for some 160 years in the 19th and 20th centuries. The six generations of Bartholomews were closely associated with Edinburgh but for the story of the first of the map-makers we have to turn to George Bartholomew (1784-1871) and his link with Dunfermline.

George Bartholomew`s early road was a rocky one. He was born out of wedlock in Edinburgh on January 9 1784 to Margaret Aitken and John Bartholomew (1). Margaret, a chambermaid, was the daughter of Robert Aitken, wright, at Parkend near Dunbar. John Bartholomew was the laird of Baldridge, Dunfermline, his lands consisting of Wester Baldridge, part of the lands of Clune lying to the west of the Baldridge Burn and a piece of the lands of Pittencrieff. He was the son of George Bartholomew, merchant, and his wife Anna Andrew, who belonged to a prosperous and respected Linlithgow family. As well as managing his estate, John was an inspector of taxes for Scotland (2). George was not John Bartholomew`s first illegitimate child as he was already the father of a baby girl, Isabell, conceived at Baldridge, but born in Linlithgow to Isabell Aitken in February 1782 (3).

Throughout their relationship, Margaret knew that John was `making an honourable address to a Lady in Kendal` and in December 1788 he married Hannah Turnbull, aged 29, daughter of the late Reverend James Turnbull of Denny. John Bartholomew and Hannah had four sons, George in 1791 (who died young), Mathew Ross in 1792, John in 1795 and George in 1799. The couple raised their sons at Baldridge House and it appears that John intended to settle there as he purchased three grave rooms in the Satur Churchyard of the Abbey from the Dunfermline Kirk Session in October 1797 (4).

After his marriage, John Bartholomew tried to wash his hands of Margaret Aitken and George, his first-born son, but Margaret, who had been `much overwhelmed with Grief` when he got married, sued him in the Commissary Court under an action called `Declarator of Marriage` for breach of promise and for the legitimisation and support of his child. The court case, which lasted intermittently from January 1789 to March 1792, takes up 282 pages in the Court Book and is full of interesting details in which the question of class plays a part and the truth is not easy to determine (5).

As the Court case reveals, the six-year affair between John and Margaret began in November 1782 at Cameron`s Inn, Edinburgh, where she was a chambermaid, and continued at Gordon`s `bawdy house` in Forrester`s Wynd, Edinburgh, `where no questions would be asked`. They also stayed together at the Press Inn, an isolated hostelry not far from Margaret`s home in Dunbar, and at various lodgings in Edinburgh. Eventually John set Margaret up at Taylor`s Land, Richmond Street, Pleasance, where on January 9th 1784 their son George was born. George was baptised by Mr. Moyes at the English Chapel, which Bartholomew had chosen because the Church of Scotland to which he belonged would not baptise his natural son without Bartholomew submitting to `a satisfaction to which he was little inclined` (a public reprimand on the stool of repentance). He believed the Episcopalians had more liberal sentiments. Over the next four years the couple stayed together in various Edinburgh lodgings and in Nicolson Street, in December 1787, while John was in London, Margaret gave birth to a second son, who lived for just 12 days (6).

The gist of Margaret`s argument was that Bartholomew had shown her great affection and given her valuable presents, including the gold ring from his finger, had been good to her family and had called their son George after his father in hopes of the boy inheriting the family money. Further he had named her as his wife in front of witnesses and at Forrester`s Wynd had taken up the Presbyterian Confession of Faith and sworn on it that he would keep his promises and vows to her and assured her that this oath was as binding as a regular marriage. It was true that John always addressed her as Margaret Aitken rather than Bartholomew but he had told her that this was only for the time being to avoid offending his father who would not approve of the match. She regarded herself as Bartholomew`s wife but he refused to co-habit with her because of his `fear of God and regard to his Conjugal vows`.

John claimed that he had never held any sort of wedding ceremony with Margaret or named her as his wife but had kept her as a paid mistress. John`s witness to this fact was his friend Henry Wellwood of Garvock, who told the court that one day, when he was joking about the girls in Baldridge, John said he had no connection with them because he had a Girl over in Edinburgh (7).

John`s lawyers claimed that `the Lybell was not proven` and added `It is not a very probable story that a Gentleman possessed of a pretty Considerable fortune and liberally Educated would treat and entertain the Chambermaid of an Inn in so familiar a manner or that he would be so foolish as Choose so amiable a Lady for his wife`.

Margaret claimed that she had marriage lines but the Court decided that this was `completely false` and other parts of her evidence unproven. The final judgement was that she had no case and `it must be held till the contrary is clearly proved that she is endeavouring to make a marriage when none was intended at the time` (8).

When the case of George, aged nearly seven, came up in December 1790, a solicitor William Scot was appointed Tutor to represent him. John Bartholomew had been summoned 12 months earlier but had put it off under various pretences and without any support George was said to be `kept destitute and in a State of Starvation`. In reply to a final summons, John said that he could not appear because his wife was in childbed and he could not leave her until she was out of danger. In evidence he stated that George`s privations could not be attributed to him as he had offered to support the child and pay for his education but this had been refused. The court accepted this and his lawyers asked the court to judge `what must be the situation of the Petitioner a man connected in matrimony with a Gentlewoman persecuted by a woman who had for some time admitted of his visits as a kept woman` (9).

The ten letters from John to his `dearest Peggy` (which Margaret had kept) and one to her father sending a gift of wool for the family, were judged to have clinched the matter in his favour because he never used the words `husband` or `wife` and always addressed her as Margaret Aitken, never Bartholomew. Whatever the judgment, the letters certainly sound husbandly in tone.

On June 3rd 1785 he wrote `I hope you will not be inconstant in my absence, you can never be happy if you are… I beg my dear you`ll take care of yourself and my favourite boy… I beg you will keep a clean handsome house, you know I like everything in that Style. You know how much I like you Dearest Girl, Your real friend, J.B. On June 5th he wrote `be sure you have the chairs properly cleaned and mended, the foot panel to the bed and the curtain properly hung. Let everything be properly cleaned and in the best order`. He asked Margaret to get two more chairs of the same pattern by the time he came to Town and also to have a kitchen chimney sought out and hoped that `In time I shall have all properly furnished to the satisfaction of my Pretty Lass`, who should be `cheerful, affable and gay, sing, laugh and be in good humour`. He said that he was much interested in the prosperity of Margaret and the boy and added that she had to stroke George`s head every night but `not to ruffle his hair but to leave that to your beloved`. He asked her not to write to him at Baldridge as he had an old housekeeper who was liable to carry tales to his father in Linlithgow (10).

In November 1787 he wrote from London sending money and said that he was sorry not to be with her at this time (late into her second pregnancy) but she should be careful of herself and easy in her mind `for this business of mine here will be so much to our advantage as make us all happy forever after`. I beg the favour you will take a walk out every day and be as happy as possible, yours affectionately, J. B. In mid-December 1787 he wrote again `I beg you will bestow all attention on yourself and George, do not vex the boy as he has got a very high spirit. I hope you have well got over your happy day (the birth of their second son), I shall be home to comfort you as soon as possible. On December 22nd when the new baby was obviously sickly he sent half a guinea and wrote that `I am very sorry indeed to hear of your situation. I have all the inclination in the world to fly to you but cannot, however, but have now succeeded in a business that will enable me to make you comfortable. You must get the child baptised yourself if necessary` (11).

On March 7th 1792 John was assoilzied (exonerated) of a declaration of marriage to Margaret and hence of the legitimisation of George, but the Court had something to add about this outcome. If it was not a marriage, it seemed like one, and Bartholomew exhibited such attachment to George as to lead to a conclusion that he must have intended providing for him. The Court suggested that, while George should be left with his mother, William Scot might proceed with a process to insure that his father paid for his lodging, food and education at an academy and entry to an apprenticeship or profession, with an income to enable him to set up in the world (12).

Whether or not Bartholomew supported George is not known but the family history states that Margaret raised her son in humble circumstances in a tenement on the south side of Edinburgh`s Old Town, probably in Richmond Court or Street near the Pleasance, in the Dumbiedykes area. Margaret may have been the M. Aitken, grocer, in Richmond Street or the Mrs. Aitken advertising furnished lodgings in Nicolson Street in 1805-7 (13).

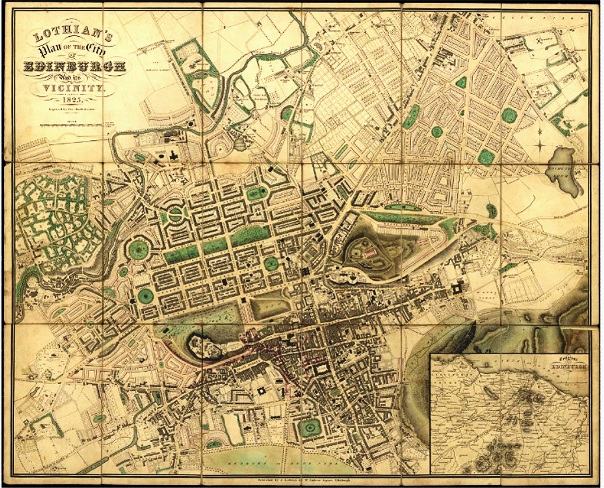

George seems to have had some education because when he was 13, by virtue of the neatness of his copperplate script, he became apprenticed for six years to Daniel Lizars, the well-known engraver at the Parliamentary Backstairs. At Lizars, George learned to do a variety of engraving work, such as book illustrations and stationery, which demonstrated his excellent lettering. In1805, about two years after completing his apprenticeship, he set up as an independent engraver while still undertaking commissions for Daniel Lizars and, after Daniel`s death in1812, for his son William Home Lizars. When Lizars moved to larger premises, George widened his skills to include map engraving on both copper and steel plates and is named as the engraver on Lothian`s Plan of Edinburgh in 1825 and Leith in 1826, and as a contributor to Wood`s town plan of Leith in 1829.

In May 1815, from 33 East Richmond Street, George married Anne McGregor from the same street, and they had ten children, six daughters and four sons, the eldest, John, having being born in 1805, ten years before the marriage (14) Sadly, the couple lost a boy and a girl in infancy and three daughters in their teens or twenties. Of the sons, George, became a Presbyterian minister while John and William followed their father as engravers after apprenticeships at Lizars. Unfortunately, William became mentally ill and from 1849 had to be institutionalised for life (15).

Although George was the first Bartholomew to become involved in map engraving, the founder of the family business was his son John (1805-1861). The story of the Bartholomew firm is well documented on-line and elsewhere and just a short summary will be given here.

The Bartholomews could not have chosen a more timely business to be in as British colonisation and missionary endeavours created a need for maps of new territories while at home cities and towns were growing and changing and people of all classes were moving to new places for work and beginning to go out and about for leisure. Later on the firm published maps to suit travellers by rail, road and air.

John Bartholomew founded the family business of John Bartholomew and Sons in 1826 and from then on it passed from father to son for four more generations. For some years in the 1850s, three generations – George, his son John senior and his grandsons John junior and Henry – worked together at 59 York Place, where they published maps and a variety of printed matter. John senior`s notable work was carried out on the GPO Directory Plan of Edinburgh of 1832, Lizars General Atlas (of the world) of 1835, and Blacks General Atlas of 1846.

Lothian’s plan of the City of Edinburgh of 1825 engraved by George Bartholomew, Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland, Creative Commons Attribution

In 1859 John senior retired and his son, John (1831-93), who had trained in London as a geographical draughtsman and engraver, took over and moved the firm to larger premises at 4a North Bridge. The firm obtained its own printing press and was advertised as a `printing and lithographic establishment`. Adam and Charles Black the publishers occupied the same building and a collaboration began that would last for 40 years. John junior specialised in layer colouring of maps to show heights and depths which were shown to effect in Baddeley`s Guide to the Lake District, Black`s Tourist Map of Scotland and Fullarton`s Royal Illustrated Atlas. In 1869 the business moved to 17 Brown Square and in 1876 to 31 Chambers Street, into which Brown Square had become incorporated.

John junior`s son (and George`s great-grandson) John George (1860-1920) worked alongside his father as a geographer and cartographer and with his father developed the first examples of contour layered coloured maps. In 1884 John George helped found the Royal Scottish Geographical Society and he received several honours for his contribution to geography. When his father retired in 1888, John George took over the company at the age of 28. He formed a partnership with Thomas Nelson the publishers and they moved the business to larger premises in Park Road, Holyrood. Success followed success and in 1910 John George was invited to become geographer and cartographer to the King, an honour the business held until 1962. At Park Road, John George renamed the business `The Edinburgh Geographical Institute`, a title that from 1911 decorated the portico of 12 Duncan Street, Newington, the company`s home until 1995 (16). Among the important projects spearheaded by John George was the Times Atlas of the World, which became Bartholomew`s most famous title.

In 1919 the firm became a private limited company John Bartholomew and Son Ltd and from 1920 was managed by John George`s son John known as Ian (1890-1962). In 1922 Ian completed the work on the Times Atlas begun by his father and in 1955-60 published a mid-century edition in five volumes to satisfy the needs of air travel.

Bartholomews continued as a family business producing maps of all kinds under the management of Ian`s three sons, John, Peter and Robert, the latter dying as late as 2014, until 1980 when it was taken over by Readers Digest and in 1985 by News International. The family maintained some involvement after this but their formal association ended at the end of the 1980s when the business merged with HarperCollins the publishers and in 1995 left Duncan Street for the Collins site at Bishopbriggs, Glasgow. The map side of the business, however, is still called Collins Bartholomew (17).

Returning to George Bartholomew, we find that he advertised as an engraver into old age and it was not until the 1871 census, just before he died, that he was recorded as a `retired engraver`. After the death of his wife Anne in 1849 he shared a home with his unmarried daughters, Margaret and Matilda at 6 Leopold Place and at other addresses around Leith Walk. In about 1865 the family moved to 6 Salisbury Place, Newington, where his son, the Rev. George, now a widower, joined them. George Bartholomew, senior, died in October 1871, aged 87, having outlived his wife by 26 years and his son John by 10. George died a wealthy man and was able to leave each daughter a house, one in Leopold Place and one in Clerk Street, and to make provision for the future care of his son William who would never be able to support himself. George Bartholomew`s death certificate states that his father was John Batholomew and his mother Margaret Bartholomew, maiden surname Aitken. Too late Margaret had the recognition she had craved.

Of the other people in this story, both the women in the life of John Bartholomew of Baldridge, Hannah Turnbull and Margaret Aitken, died in 1808: Margaret died relatively young but had at least lived to see her son launched on a promising career. John Bartholomew sold much of his land to Thomas, Earl of Elgin and Kincardine, in January1788, although he continued to live in Baldridge House with his family until about 1803. He died on September 28 1816 aged 62 at Raeburn Place Edinburgh where he lived with his son Mathew Ross. He seems to have accepted his responsibility for George as a provision of his disposition and settlement was that his legitimate sons ensured that his `natural son George` had £200 and a share of his estate.

George the youngest of three Bartholomew boys born at Baldridge died at Madeira in 1819 aged 20 while he was a midshipman on HMS Leven. John, the middle son, an Edinburgh advocate, died aged 40 in1836 from `decline`, which was probably tuberculosis. John made his half-brother George one of his trustees and included him in his bequests, and the names of John Bartholomew advocate and his infant son appear on George Bartholomew`s family grave in Warriston Cemetery (18).

Mathew Ross Bartholomew, the eldest of the three, moved to London and died there in 1841 aged 48. Although Mathew`s obituary states that he was the only surviving son of John Bartholomew of Baldridge, ignoring the existence of George, he left to `Mr. George Bartholomew, engraver, of Leopold Place, Edinburgh`, insurance policies and the rest of his estate and effects.

George Bartholomew may have had a poor start in life as the illegitimate son of a Dunfermline laird but he lived to a ripe old age and by the time he died had become the patriarch of a talented, successful and prosperous family and had seen the name of Bartholomew on its way to becoming a byword for excellence in the map-making world.

Notes and Sources:

Bartholomew family and company details come from websites, including `Grace`s Guide`, `Bartholomew: A Scottish family history` and `Bartholomew family and firm`, the Bartholomew Archive, National Library of Scotland. Other personal details come from Scotlandspeople website and the National Archives.gov.uk. The original entries in parish records and censuses, particularly regarding ages, were not always accurate).

1. Margaret Aitken (1758-1808), John Bartholomew (1754-1816). Margaret may have been born in 1761 rather than 1758 and I have found no proof of her date of death.

2. John Bartholomew was appointed Inspector of Taxes (a new appointment) in 1780 at a salary of £100 a year. His father, George Bartholomew, built a substantial house in Linlithgow High Street which later became Annet House Museum. The Baldridge family seemed proud of being landowners and John was known as `John Bartholomew of Baldridge` as late as 1848 when his son Mathew died.

3. Linlithgow Kirk Session Minutes, Feb. 24 1782, March 10 1782, April 7 1782 – `Isabel Aitken compeared before the session and declared that she had brought forth a child in uncleanness to John Bartholomew of Wester Baldridge in Dunfermline Parish where the child was begotten about the beginning of June`. Dunfermline Kirk Session Minutes, Volume 9, March 3 1782 (digitalised at the National Records of Scotland). This case led to a heated debate (never properly resolved) between the two kirk sessions about whether responsibility for the case laid with the mother`s parish or that where `the guilt` had taken place. Whether Isobell and Margaret Aitken were related is unclear.

4. Dunfermline Kirk Session Minutes, Oct. 23rd 1797.

5. Commissary Court of Edinburgh (CC), National Records of Scotland, CC8/5/20. Details of the case appear in Leah Leneman, `Wives and mistresses in Eighteenth-Century Scotland`, Women`s History Review, Vol 8, No. 4, 1999, pp. 671-692.

6. The proprietor of Cameron`s Inn was Hugh Cameron, vintner in Edinburgh.

7. CC, passim.

8. CC, p. 947.

9. CC, p. 752.

10. CC, p. 788.

11. CC, p.1004-5.

12. CC, p.1011-3, p.1024.

13. Edinburgh and Leith Directories, 1800-1810.

14. George and Anne probably delayed their marriage for ten years because Anne was only 14 or 15 when their son John was born in 1805.

15. William (1819-1881), who had been a hatter as well as an engraver, spent the rest of his life in asylums in Dumfries and Edinburgh, where he created skilful, sometimes bizarre, works of art. Maureen Park, Art in Madness: Dr. W. A. F. Browne`s Collection of Patient Art at Crichton Royal Hospital, Dumfries, 2010. Kathryn Powell `Out of sight, out of mind: the visual archives of asylum artist-patient William Bartholomew, 1853-1877, MA Thesis, University of British Columbia, 2018.

16. Now Bartholomew House and Mapmakers Townhouse consisting of quality apartments and holiday lets.

17. Collins Bartholomew websites.

18. `Find a grave` website: photograph by John Bartholomew.