Lighting Up Dunfermline

Lighting up Dunfermline and Public Announcements.

by George Robertson, FSAScot.

Once again we turn to Alexander Stewart’s Reminiscences of Dunfermline, this time for information on the early lighting system in Dunfermline and also on how information was relayed to the inhabitants of the town. In this respect, we are lucky as Stewart gives us a first-hand account of life in Dunfermline during the early 19th century, something he personally experienced and obviously closely observed and what follows is in his own words with later comments by this author.

“Fifty-five years ago (circa 1830’s) there was no gas lamp in the town. The streets were lit up with lamps here and there, placed at wide intervals, and they were furnished with train oil and cotton wick. The feeble glimmer they struggled to send forth only served to make the darkness visible. After burning for a few hours in a sickly way, the lamplighter, with his ladder over his shoulder, went his rounds and blew them out. In dwelling-houses and shops, candles, called long sixes or short sixes, long or short eights, tens etc., also oil lamps, or the ancient cruisie, were used at night. The cruisie was a very primitive lamp, having one or perhaps sometimes two wicks; it was fed with train oil, and it gave a dim light and a disagreeable odour to the house.

“Churches, when used in the winter evenings, and places for public meetings, were lit with tallow candles, placed in large uncouth-looking candelabra, which hung from the ceiling by cords attached to pulleys, to enable them to be pulled up or down. The aspect of a congregation or public meeting was dull and gloomy in the extreme. On a Sabbath evening the candles in the churches had to be snuffed during the service; and it happened sometimes, when the beadle was an awkward hand at the business, he would snuff out one, or sometimes two by mistake, or even occasionally knock a burning candle down upon a lady’s bonnet! This would cause quite a titter in the congregation, and disturb the equanimity of the minister. In other cases, if the candles were not of a good quality, or if they were burning where there was a draught, serious damage was often done to those sitting below the candelabra, by the falling of grease over their heads and shoulders. An elderly lady recently told the writer that a very handsome shawl, which had been presented to her, was found one Sabbath morning when she was going to dress for church to be badly stained with grease. As she was not in the habit of going to the church at night, it was discovered that one of the servants in the house where she was staying on a visit had actually gone to the lady’s trunk, taken out the shawl, and worn it at an evening’s service. “Murder will out!”

“There were then no fine Lucifer matches, vestas, and other similar useful conveniences. Tinder-boxes, containing tinder made of burnt linen, along with a steel and flint, were used to light the sulphur “spunks” with which the fires were kindled. The tinder-box was flat, and usually made of tin. With the steel and flint a spark was struck, which, alighting amongst the tinder, caused it to light the sulphur “spunk.” It was a tedious way of making a fire, and bellows were then rarely used. Numerous spunk-vendors used to go from door to door with bundles of “spunks” slung over their shoulders, calling out, “Are ye needin’ ony spunks the day?” This was a great industry even then, requiring little capital and yielding good profits; but as a class of artisans, the spunk makers, like the makers of heather besoms, stood on a very low platform in the community. Mostly every household had a hand lantern for the dark nights of winter, and when those lanterns were seen in the dark flitting along in the dim distance in all directions, they gave the streets a weird-like appearance. The youngsters of the present day will not know what a “save-all” was, but the working-men of the times, who were anxious to economise every inch of their tallow-candles, knew well the use and the value of this little contrivance for saving.

“With all their want of artificial light, the worthy people of those days did not break their hearts over the circumstance, for the simple reason that they neither felt the loss nor knew the benefit of our modern improvements and comforts, and were happy with what they had. A day may likely come when future generations will look back with pity and amazement upon us, for having been able to exist without the benefits of electricity as a light in our dwelling-houses, and more especially as a motive power to drive sewing-machines and washing-machines, and perform many other domestic duties. It has been remarked that “the moderns of that day are the ancients of ours, and we speculate upon them in this present year of grace as our children’s children, a hundred years hence, will give their judgement about us.” If our forefathers had no sewing-machines, garments were made simpler and plainer than at present; and if news did not come so quickly, there was far more leisure to consider and ponder the information that was received. If there were no railway trains and tram-cars, there was in general the ability to walk long distances, and a journey of ten or twenty miles was then thought nothing of. For many of the inconveniences they suffered they were compensated in other ways, and their lives were not quite as dreary as young people of the present day would suppose.

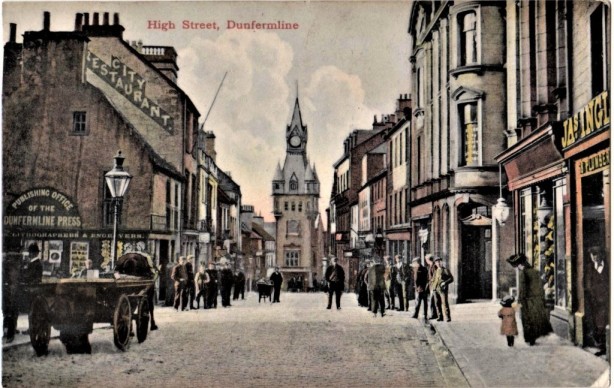

“There was then little or nothing done in Dunfermline in the way of newspaper advertising. No one was in any special haste, and people took things easy. At the same time, while they were never in a hurry, they were never idle, but always industrious. Competition was almost nil, and there was no need for crowing cocks and other startling newspaper illustrations and devices to attract public attention. Public intimations were universally made by the town’s drummer and the bellman. The cost of the drum giving a certain fixed round, was, I think, one shilling, and the bell threepence. Bell Mary flourished about sixty years ago, and Sandy Finlayson and other quaint characters succeeded her. The style of intimation differed very much, as did the different criers themselves. There was often a touch of humour and sometimes pathos in their advertisements. It might be that a lady’s black silk bag had gone missing between the “fit o’ Geelies Wynd (now known as Reid Street) and the Rotten Raw”, (west end of Queen Anne Street, at its junction with Bruce Street), or about “a wee bit bairnie that was lost this mornin’, at the back o’ the dam (north end of Bruce Street, now disappeared under the Tesco superstore); it had a white curly headie, an’ wore a blue chacket daidlie (checked pinafore). It is supposed that the aforesaid little bairnie had wandered after its faither when he gaed till’s wark aboot the aforesaid time. Whoever has found the same, by returning it to me, or its distractit pawrents, will be weel rewardit an’ paid for their pains.” Or it might be that “there had arrived at the Tron (south end of High Street) twa cartload o’ caller haddies (freshly caught haddock) and green skate, twal’ pund (twelve pound) for saxpence, – noo’s the time for your bargains;” or “there can noo be obtained every nicht, between sax and aucht o’clock, het penny pies an’ tippeny ains, at the pie-office, next door to Jenny Barclay’s in the Kirkgate.” (1)

Stewart names three people in his article, Bell Mary, Jenny Barclay and Sandy Finlayson. Of the first two nothing further has been found but there is a reference to Sandy Finlayson, whom Stewart describes as being one of the “quaint characters” of the town, this being found in Daniel Thomson’s Anent Dunfermline. Thomson gives us afulsome description of a Dunfermline man of the same name, presumably the same person. This Sandy Finlayson is described by Thomson as being –

“A character of weak intellect but of smart and clean habits. He had a curious lameness which caused him to twist the foot to half face position when walking. He had a strange defection in a kind of swallowing stutter in his speech and a comical habit of mixing his words and sense in an upside-down kind of way.

“Through good offices of his weaver friends in the south-side he got a small pony and cart by subscription. When he was allowed to stow his little waggon in the half roofless recess of Milton Green Mill (south west side Dunfermline) he harangued the boys who waited on his evening advent in his fearful stuttering fashion on the necessity of respecting the cart saying to the boys it was a subscription cart and “a’ their fathers had carted a shilling to the subscription” – this being an example of Finlayson getting the cart before the subscription!

“When on one occasion he found on his travels a gold ring, he brought it to his lodgings in a highly gleeful manner exclaiming – “A getting fit’s aye gaun” – this being a reversal of the saying – “A gaun fit is aye getting!” (2)

Whether this is the same Sandy Finlayson mentioned by Stewart is unclear but comparing the brief description he gives of his Sandy and the Sandy Thomson described by Thomson, it seems likely this is the case.

It will be noted, Stewart does not give the name of any of the Town’s Drummers. However, two of these men have been traced, the first being James Dow, who on 1st February, 1831, perished in a snow storm whilst returning home after delivering a message to Headwell Farm. He was found dead the next morning, resting on his knees, a few hundred yards from where he had delivered the message. (3) Moving forward sixty years we find yet another named, he being Richard Drysdale of Baldridgeburn, who, during February of 1890, was appointed Town Drummer by Dunfermline Town Council. (4) Drysdale’s name is again noted in 1892 when, during December of that year, he appealed to the Town Council for a new uniform as the one he was in possession of was “inadequate to uphold the honour and dignity of this ancient burgh.” Unfortunately, the appeal fell on deaf ears it being decided since Drysdale had taken on additional employment as bill-poster and coal carrier, which he had found necessary as his duties as Town Drummer no longer provided him with sufficient income, the Council claimed these latter duties were not “calculated to add lustre to the historic town,” and a new uniform would not be provided. (5) It is not known if Drysdale appealed this decision.

Stewart tells us of the conditions which existed in the homes of the citizens of Dunfermline during the early 19th century were, to say the least, not very nice, describing smelly cruisie lamps, oil lamps and candles, all of which were no doubt dangerous to live with considering the constant risk of fire. He also describes the streets of the town being ill-lit by oil burning street lamps which were obviously inadequate for the purpose. According to Henderson’s Annals of Dunfermline, during June, 1752, the Town Council agreed the first of these lamps, six in number, should be ordered for the streets of the town, each costing twelve shillings sterling. Four Councillors were appointed to ensure the lamps were placed at appropriate places but three months later the Council decided six lamps were not sufficient for the purpose of giving adequate street lighting and a further six lamps were ordered. (6) The following year the Town Council “agreed to give Robert Meldrum and David Chrystie, Ten Pounds Scots betwixt them for lighting the lamps each Year, and for otherways (sic) taking care of the said lamps, and the Council also further agreed to furnish them with three punds (sic) of candle for lighting these lamps” (7) However, the number of lamps purchased was still found to be inadequate and, at various times, further lamps were purchased until by 1813 a total of 115 lamps were lighting the streets of the town. (8)

By 1828 oil street lamps were in the process of becoming redundant as another source of power was about to be brought into use – gas. The change over from oil to gas came about due to Dunfermline Gas-light Company setting up a gas works at the west end of Priory Lane and, on the evening of Wednesday, 28th October, 1829, the Company turned on the gas supply for the houses, shops and other premises in the town. Henderson, in his Annals, tells us “the streets were crowded with town and country people to see the grand sight.” (9) The Priory Lane gasworks remained in use until 1893 at which time the Directors of the Company decided the works was “too small to meet demand for gas from town and country and were then constructing a new gas works on Grange Road.” (10)

In his article, Stewart ponders on a “remark made by another” (see Notes) concerning how “our children’s children, a hundred years hence, will give their judgement about us,” and it could be said he is referring to us as we are the children, grandchildren or great grandchildren of those children. No doubt we each have our own view of life in those far off days, but I am certain we will at least agree it was very different from what we experience today. Maybe we should be asking ourselves what, in another hundred years, the children and grandchildren of our children will be thinking of what we have – or have not – achieved.

References:-

- Reminiscences of Dunfermline- Sixty Years Ago, by Alexander Stewart, published 1886, by Scott Ferguson and J. Menzies & Co., Edinburgh and Simkin, Marshall & Co., London, pp 25-28.

- Anent Dunfermline, by Daniel Thomson, Vol. 2, Item 627.

- Perthshire Courier newspaper dated 17th February, 1831, p.4.

- Fife Journal newspaper dated Thursday, 14th August, 1890, p.5.

- Dundee Courier newspaper dated Wednesday, 14th December, 1892, p.2.

- The Annals of Dunfermline and Vicinity, by Ebenezer Henderson, L.L.D., published 1879, by John Tweed, Glasgow, p.459.

- Ibid, p.465.

- The Scottish Burgh Survey – Historic Dunfermline, Archaeology and Development, by E. Patricia Dennison and Simon Stronach, published 2007, by Dunfermline Burgh Survey; Community Project, p.57.

- The Annals of Dunfermline – as at (6) above, pp 627-628.

- Dundee Evening Telegraph newspaper, dated Saturday 20th May, 1893, p.2.

Notes:-

Stewart’s comment about a “remark made by another” refers to a comment made by William Makepeace Thackeray (1811-1863), which appeared in Chapter 41, entitled “Rakes Progress”, of his book The Virginian – A Tale of the Last Century, which was published in London during 1859.

The image of the Lamplighter is to be found at Plate 29, in the book entitled The Costume of Great Britain, designed, engraved and written by William Henry Pyne, published 1808 by William Miller, London.

The cruisie oil lamp shown in the article can be found on display within the Andrew Carnegie Birthplace and Museum, Dunfermline. My thanks to Beth Cameron for photographing the lamp.

The image of the bell-man appears on page 525 of the Annals of Dunfermline, by Ebenezer Henderson.