Harleys Acres

By Sue Mowat

Among the papers in the Pittencrieff estate deed box in the Local Studies Library is a small notebook containing details of all the feus granted by the Hunts of Pittencrieff on their estate between 1800 and 1837. Most of the street and place names in the list are familiar, like Golfdrum, Whitemire, Woodhead Street (now Chalmers Street) and Pittencrieff Street, but between 1827 and 1830 six feus were granted in an area called ‘Harley’s Acres’. Where on the estate could that have been? The only clue in the notebook to the location of the ‘Acres’ was that all the feus were on the north side of ‘Back Street’, the eastward continuation of Queen Anne Street (now James Street).

Once again the 1771 map of the Pittencrieff estate came to the rescue, showing that the laird owned a large field called ‘Back Acres’ in the north-eastern area of the town, whose southern boundary was the eastern continuation of Queen Anne Street.

Once again the 1771 map of the Pittencrieff estate came to the rescue, showing that the laird owned a large field called ‘Back Acres’ in the north-eastern area of the town, whose southern boundary was the eastern continuation of Queen Anne Street.

This identification was confirmed by an item in the records of the Marquis of Tweeddale’s lands in Fife (which he owned as successor to the Lord of the Regality of Dunfermline). In 1810 William Hunt of Pittencrieff owed the Marquis £5 12/6d cash and 5 poultry as rental of ‘five acres of the Backside, formerly Harley’. The entry in the record was followed by a note that this was part of the lands that owed dues to St Leonard’s Hospital. (The apparent discrepancy between the Tweeddale acreage and the one on the map is owing to the fact that one is Scots acreage and the other is Imperial acreage, a Scots acre being larger than an Imperial acre.)

The 1854 OS map (see below) further confirmed the identification, showing the six feus on the north side of the newly-named James Street, the meeting house shown on the 1771 map having now become a Baptist Chapel. It has been fancifully stated that James Street was named after James VI, but an article published in the Dunfermline Press in 1860 reveals that the ‘James’ in question was James Inglis, a prominent linen manufacturer who was heavily involved in civic affairs and very influential in the town.

So far, so good, but the question remains – who was Harley?

The most likely 18th century candidates were two prominent Dunfermline weavers of that name, John and Archibald Harley, who seem to have been father and son, an Archibald Harley being admitted to the Incorporation of Weavers in 1724 and a John Harley in 1748. Harley was not a common name in Dunfermline at the time and these two are the only Harleys recorded as being of sufficient status to have owned property.

John Harley

John Harley was described as a merchant and manufacturer, meaning that he employed weavers to produce linen which he then sold. In 1751 he married Margaret Chalmers and all of their six children were baptised at the Erskine Church, Archibald Harley being a witness at most of the baptisms. The couple lived in a house that John had built in Shaddows Wynd (Bonnar Street). John was the more civic-minded than Archibald. In 1761 he was elected Burgh Treasurer and by 1765 was a bailie and member of the Dean of Guild Court. Two years later he was Dean of Guild.

By 1769 John Harley’s business was in difficulties and this advertisement appeared in the Caledonian Mercury of 4 September.

Perhaps his problems were caused by failing health because two years later he died. The household goods listed in his inventory suggest that his house was a modest one, with a two-loom shop and kitchen on the ground floor, a couple of living rooms above that and a garret. He had held the leases of Bellyeoman and another farm belonging to the town called Plealands and among his moveable goods were some farming implements, four horses and a cow.

Archibald Harley

Archibald Harley married Isobel Stark in 1740 and the couple lived in a house in East Port (if Archibald was in fact John Harley’s father, Isobel must have been his second wife). Archibald played a small part in civic affairs, being Deacon of the Incorporation of Weavers from 1746 to 1748, which automatically gained him a seat on the Town Council, and in about 1750 he served as Deacon Convener of the Trades of Dunfermline. John Harley seems to have leased his arable land, but Archibald was an owner. In 1745 he applied to the Town Council for a lease of the Holy Blood Acre (near site of the current Police Station) in the backside of the Burgh with the ‘back way’ on its south side. The relevant entry in the minutes of the Town Council states that Archibald Harley owned the land to the east and to the west of the Holy Blood Acre, his western holding being the ‘Back Acres’ shown on the 1771 map.

Archibald Harley died in 1772. He had stood as cautioner for payment of a loan by the Kirk Session to John Harley and Adam French and was liable to pay the outstanding interest of £42. He left no will and the current treasurer of the Kirk Session was appointed his executor for recovery of the interest. Archibald’s moveable assets, which was all the creditor could claim, were few – rents of a barn and barn yard and two dwelling houses amounted to £4 1s. His household goods were rouped (auctioned) and after payment of his funeral expenses just £3 9/2½d was left, so the Kirk gained a total of £7 10/2½d.

As ‘Harley’s Acres’ belonged to the Pittencrieff estate by 1771, Archibald Harley must have sold the field to the laird at some time previously. The land remained undeveloped until the feus were granted by James Hunt of Pittencrieff between 1827 and 1830, as shown in this table:

| 1827 | 1827 | 1827 | 1828 | 1829 | 1830 |

| John Walls carrier | Robert Macara watchmaker | Thomas Williamson horse dealer | Alexander Henderson shoemaker | John Gibson weaver | James Webster upholsterer |

The six feus are shown clearly on the 1854 Ordnance Survey plan of Dunfermline and it is noticeable that John Walls’ feu was a double-width plot.

Developments in the Nineteenth Century

By the time the OS plan was made much had happened in the Back Acres. In 1847 the first sod of a railway line between Stirling and Dunfermline had been cut at Milesmark and the Back Acres had become the site of Dunfermline’s first railway station, which opened in 1849.

The condition of Dunfermline’s streets was much improved during the first half of the 19th century. Pavements were laid, roadways were surfaced, more effective street lighting was installed and in 1856 a piped sewage system was laid. All these improvements, however, only applied within the Burgh boundary and the dreadful conditions in the suburbs, which included a large part of the Pittencrieff estate, became increasingly obvious in contrast to the amenities within the Burgh and in the early 1860s a strong movement arose in favour of extending the boundaries to include the suburbs. In spite of vigorous opposition by James Alexander Hunt of Pittencrieff, who held up progress for two years through legal actions against the Town Council, finally in 1867 the necessary law was passed and the boundaries were extended. In July of that year the Dunfermline Press reported on the new boundaries, which included the former ‘Harley’s Acres’.

From the south-east corner of the feu on the north side of James Street, belonging to Alexander Roy, cabinetmaker, (originally James Webster) northward along the east boundary wall of the said feu.

From the south-east corner of the feu on the north side of James Street, belonging to Alexander Roy, cabinetmaker, (originally James Webster) northward along the east boundary wall of the said feu.

From the termination of the said wall in a straight line to the hedge or fence separating Pilmuir Park from the park formerly known as Mr Hunt’s Park, now belonging to the North British Railway Company on the north side of their station.

Thence westwards along said hedge or fence and the south boundary walls or fences of the feus on the south side of Campbell St belonging to William Moir, Robert Fisher and George Anderson, to the old west boundary wall of said park, formerly called Mr Hunt’s Park.

Thence southward along the west boundary of said park and a straight line running parallel with the backs of the houses on the east side of South Inglis St, but 18 inches east thereof, to the north enclosing wall of the Baptist Chapel in James Street.

Thence eastwards along the last-mentioned wall and the north boundary walls of the properties of Mr Robert Wilson and Mrs James Aitken.

Thence southward along the east boundary of Mrs Aitken’s property to James Street and from then eastward along the channel or gutter on the north side of said street to the point first described. One result of the extension of the boundaries was that the Town Council was able to enforce the surfacing of the access road to the railway station, which for the past twenty-eight years had been nothing but a muddy track.

The Twentieth Century

In 1890 the station was named ‘Dunfermline Upper’ to distinguish it from the station to the south of the town (now Dunfermline Town) that gave access to the line across the new Forth Railway Bridge.

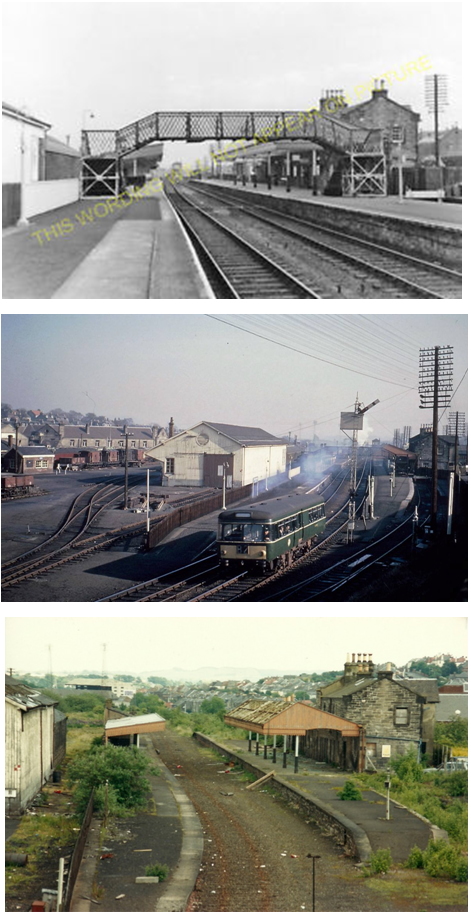

Top -Dunfermline Upper Station in its Heyday. Centre – The Station in Use. Bottom – After Removal of the Footbridge and Track.

After passenger services ceased in 1968 the station became derelict, although freight traffic continued until 1979 when the line finally closed and the track bed was lifted. In 1989 the current retail park was built on the site.

The Feus

Great changes were also happening to the feus on the north side of James Street. In the 1970s a dual carriageway, Carnegie Drive, was constructed to the south of the Upper Station site and in 1984/5, when a multi-storey car park and bus station were built on the south side of Carnegie Drive, the buildings on the north side of James Street were demolished.

The ‘Temporary Car Park’ sign is pointing down Upper Station Road to a car park on the site of the old railway station.

1980s Aerial View Showing the Multi-storey Car Park, the Bus Station, Carnegie Drive

and the Site of the Upper Station

In 2008/9 the bus station itself was demolished to make way for the Debenhams store that was built on the site. A new bus station was established in Pilmuir Street (see the blog ‘Before the Bus Station’).

Conclusion

Perhaps any attempt to ‘conclude’ the development of Harley’s Acres is premature – nothing lasts for ever, especially where Town Planning is concerned, and there are bound to be yet more changes in the future. However, tracing the development of one small area of Dunfermline over two and a half centuries is an instructive exercise. Harley’s Acres lay on the periphery of the original Burgh and the changes that took place on the ground are interesting but not archaeologically crucial. The same could not be said of any future development in the town centre, which is the heart of the twelfth century burgh.

It is a scandal that the Kingsgate Centre was built over a large part of Queen Anne Street, one of the early streets of the Burgh, with no archaeological investigation in advance of construction, in spite of legislation that requires a developer to finance at least an exploratory dig on an historical site. Let us hope that in future Fife Council will be more aware of the importance of the medieval areas of Dunfermline and will not allow such wanton destruction to occur again.