by Dr Jean Barclay

David Paton is a somewhat neglected member of the famous Paton family of artists, sculptors and designers but according to his friend, Dr. Ebenezer Henderson, astronomer and historian of Dunfermline, he was a `great mechanical genius` (1).

David was born in Dunfermline on September 9th 1766 to John Paton, weaver of Damside Street, and his wife Agnes Deans and baptised at the Dunfermline Associate (Secession) Church, Queen Anne Street, a few days later (2). David grew up to become a hand-loom weaver like his father but throughout his long life found additional ways of earning a living.

In 1791, aged 26, David married Margaret Waller at Queen Anne Street Church and they had one daughter Elizabeth, and three sons, John, Joseph and David, who was born in 1800 in Collier Row, now Bruce Street (3). David`s wife, Margaret, died in 1803 or early 1804, aged only 34, leaving four young children, and in December 1804 David married Catherine Nisbet of Carnock, with whom he had two daughters, Mary and Agnes, and a son Neil (4).

David probably did fairly well as a weaver at first as in March 1792 he was able to purchase from the Town a small yard `below the walls` (now Canmore Street). In September 1794 David, aged 28, was admitted into the incorporation of weavers and ten years later, in a time of hardship, he was one of ten weavers to frame a petition to the local MP for the repeal of a recent Corn Bill which had raised duties on corn and hence the price of bread (5).

A financial boost came in January 1809 when the Burgh Council appointed David town drummer and piper in place of George Simpson, deceased. At the outset David was not to be employed as an ordinary town officer `but he shall merely receive the emoluments paid him by those who employ him as Drummer`. However, he was to obey the Magistrates and Council at all times and to act as Officer when required by them, `upon being paid for his Extra Trouble`. Whereas the two town officers wore red coats and vests and cocked hats trimmed with while lace, David was to be issued with a short blue coat with white collar and cuffs, a round hat and a white belt and trimmings. However, he was later named as `town officer and drummer`, a position he held for four years. He was also one of three drummers in the band of the Volunteers who were mustered in the first decade of the 19th century amid fears of a French invasion (6).

In September 1813, the Provost, David Wilson, reported that `David Patton, Drummer and Town Officer, having given cause of offense to the Magistrates by misconduct, had in consequence of their reproof, Resigned his situation`. As we will see, the `reproof` may have arisen through something David had written. Fortunately, he was immediately appointed drummer and piper for the people of Pittencrieff Street and the surrounding area who had formed themselves into a New Town and erected their own tron or trading place north east of the street where they sold various commodities. In Pittencrieff, David had to beat his drum between five and six each morning to rouse the folk to work, and to play his pipe through the street before 10pm as a warning that bedtime had come (7).

David has been described as `one of the race of clever weavers which Dunfermline`s supremacy in the linen trade was breeding at the time` and, apart from `genius on the loom`, he also `had the spark of inventiveness burning in him during his whole long life`. One of the first of David`s inventions was a self-rocking cradle which was supposed to free his wife for winding the pirns or bobbins for his loom, but it proved a mixed blessing. Yes, it worked, but as David ruefully complained `it maks sic a blastit noise that it waukens the bairn` (8).

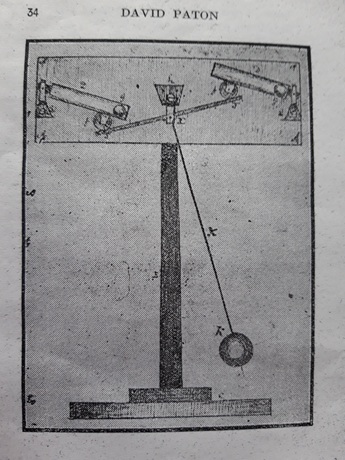

David also constructed a lathe and, as a turner, supplied a variety of items, including pirns for the weavers and peeries for the boys. Dr. Henderson, a practical man himself, spent many leisure hours in his youth in David`s little workshop which was `quite a repository of art and science, being well filled with all kinds of mechanical nick-nacks of his own making, finished and unfinished, such as box camera obscura`s (sic); telescopes and microscopes; a magic lantern made out of an old tea chest, a Franklin harmonicon; wooden clocks, common and astronomical; a planetarium, constructed with wooden wheels, the teeth of which were cut with a knife and finished up with a file, but which, nevertheless, showed very satisfactorily the motion of all the then known planets round the sun` (9). His clocks were sometimes of a curious design; some were musical and `played upon harmoniums – tiny drums and fifes!` He also made kaleidoscopes and mills for twining thread including one with a mouse driving the wheel. In 1823, David constructed a promising `perpetual motion machine` but it only worked for seven and a half minutes. He took such setbacks in his stride and merely observed, like Burns, that `the best-laid schemes o` mice an` men gang aft a-gley` (10)

Then there was the `curious printing press` that David constructed in 1810. He procured some old types for most of his printing but designed his own initial letters and illustrations and painstakingly made woodcuts of them from plane wood, using just a penknife, a small chisel, and awl and sprig bits or brugs. With this press David began printing funeral letters, advertisements, songs and, from 1811, several little book The first of these went into three editions between 1811 and 1815 and is described below (11).

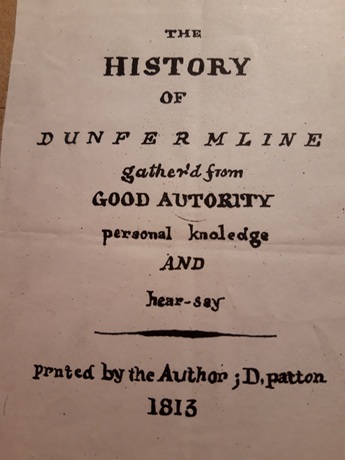

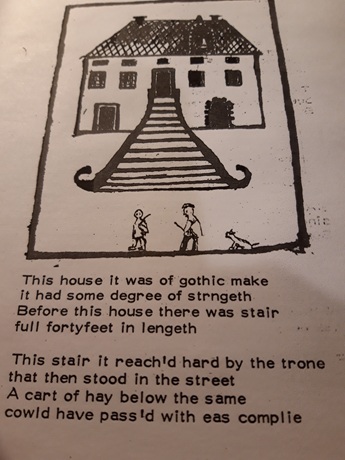

In 1813, wrote and printed `The History of Dunfermline: gathered from Good Authority personal knowledge and hear-say`. The book is 21 pages long, is written in verse, and consists of two parts. In Part 1, David recounts the history of his native town to a stranger while Part 2 is `a modern account`. It includes seven woodcuts of Dunfermline buildings – the tower brig, the old Abbey, the Abbey Church, Chalmers` Bridge, the Guildhall and the Old and New Town Houses. The woodcuts were rough and simple, but as David wrote:

As my materials was not good

I`ve given you`d as I had it

Consider the towels (tools) where with I wrought

Who cou`d have better made it.

David also compared his dress with that of the stranger. He admitted that his `pladden hoes & gunmouth`d breaks`, his `bonnet and coat of gray`, probably looked old-fashioned now, but the modern `short boded gouns and Emeral` and shoe buckles instead of ponts or laces seemed strange to him. Of the weaving industry, David explained that trade used to be `not great` and consisted of `dornicks cowrse and fine` and poor quality diaper, but much fine damask was now woven, sent to London merchants by sea and then all over the world so that `Both Affrica and Indea too has there tables with it dres`d` (12).

In 1813, too, came the `Proceedings of a Craw Club held in Fife on the Fourth of June as reported by Peter the Plowman` printed for a Craw Club, by D. Patton, Dunfermline. The aim of the Craw Club was to rid Fife of crows and its resolutions included the shooting of `the black robbers` by every landowner and a penny being offered for every dead crow. This booklet of 22 pages was very rare and Dr. Henderson believed he had the only one left (13).

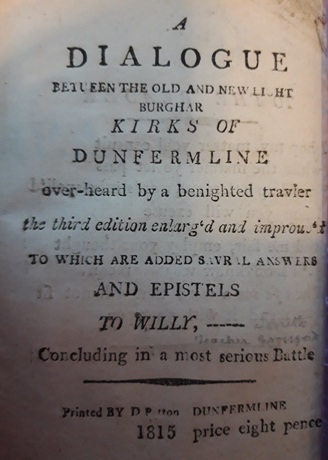

One of David`s publications proved problematic. In the early 19th century the Secession Church had split into Burgher and Anti-Burgher sects, and then into Burgher Old Licht (Light) and New Licht factions, who were bitterly opposed to each other. David originally favoured the Old Lights but found them too dogmatic and veered towards the New. In 1811 he had composed and printed 30 copies of a small book entitled (in transcription) `A Dialogue Betwixt the Old and New Burgher Kirks of Dunfermline overheard by a benighted Traveller, to which is Added An elegy on the Much Lamented death of The Rev. Mr Campbell, AM., 1811`.

Written in verse and prose, the Dialogue had 36 pages with 18 woodcuts, while the Elegy added 8 pages and included a portrait of the Rev. Campbell. The elegy of the young minister is moving and begins: `Old burgars nou you`v lost a friend, there`s feu I fear his place will mend, your pulpits toom to you indeed, yon Campbile`s gone who did you feed`.

In the main part of the book, David criticised both the Old and New Lights for their mutual animosity and ended by observing:

For we are all but travellers here

O why at one another laugh and jeer

As we were for som` other where

Than for heaven

Tis the will of God we should be there

I`m pretty certain (14).

A second edition of 50 copies followed with moderate sales, and in 1815, in response to criticism, came a third, enlarged and improved. In his `History of Dunfermline` David apologised for the roughness of his woodcuts, here he hoped that his readers would excuse his `turn`d up letterers and words miss-spelled`, adding:

Read me fair, employ your thought

Ye`ll soon know what I mean,

When ye see a word that will not fit

Pray mend it with your pen.

In a section `to the reader` David explained that a third edition of the Dialogue had become necessary because he had been `attacked in such an odious manner by William Smith, teacher from Crossford and Old Light advocate, in a booklet entitled `A defence of the genuine Burgher Secession principles…the good old way defended`…a poem in answer to a certain poem, lately published by D.P. Drummer..`.

The third edition had eight new woodcuts and 115 pages, including a preface in prose followed by verses setting out, in Old Light and New Light sections, the merits and problems with both churches. This is followed by several small sections, including addresses to the reader and to the press, an address to the Old Light Church, an address to Willy and a post-script.

In describing the churches and their faults, David used dance as a metaphor. For example he wrote of the Old Lights, which had fewer followers than the New:

I think your dance is nearly o`er

For there`s but few upon the floor

When ere the dance is done I`m sure

The fiddle stops

But yet ye think ye`ll gather more

Is still your hopes (15).

In the post-script, David used another extended metaphor in a plea for toleration. Likening the branches of the Kirk to naval squadrons, he wrote that the Old Lichts were like a squadron of `old craz`d ships`…`roaming about on the sea of the reformation alieving (sic) some and terrifying others into their way and inflicting punishment on whomsoever they would`. Willy, himself, wrote David, resembled Don Quixote `being a half witted fellow more forward than wise`, who seeing a windmill with its awkward appearance (the New Light Kirk) resolved upon conquering it. By contrast, the Toleration fleet kept `our squadron in check` with its Admiral `whose name was Moderation going on board of each ship in these squadrons Proclaiming freedom to ALL and none is to be allowed to molest another`. Among Willy`s accusations had been that David `had pilfer`d from Burns` to which David replied that to quote from an author`s work was surely a compliment and `deed Willy I dubt it wid be a while before any quot from yours` (16).

It may have been David`s outspokenness, especially his criticism of the Old Light Kirk, in his first two editions that upset the Council and put paid to his career as the Burgh drummer and he observed ruefully that:

When first I wrot upon this head a man in armer stout I made

He stood in front of Old Light stade in a war-like stile

Little thought I the sword he had would pierce mysell

Indeed it is told me by some

That for this POEM I lost my drum

My life it`s spaired no thanks to some (17).

Between 1820 and 1822, David published `A collection of excellent new songs, and other pieces on different subjects` of 104 pages with 22 woodcuts, but there were only 30 copies and Dr. Henderson again believed that his copy was the only one extant (18).

While being admired for his skill, in later years David became well-known about the town as `Old Davie Paton`, an eccentric figure with a droll sense of humour. In 1830, David joined the newly-formed Unitarian Church but little else is known about his later years (19). With the decline of hand-loom weaving, he probably just made what he could from his wood-turning while carrying on with his inventions. For some years, he lived at Wooers Alley where in 1837 his son Joseph had built a substantial house and he died there in 1844 aged 78. It was said that Dr. Henderson had wanted to write a biography of his old friend but members of his family considered that he had been too humble a man (20). Humble he may have been and probably never wealthy but his imagination and practical skill were handed down to his son Joseph, a gifted pattern designer for the linen trade, and to his grand-children, the sculptress, Amelia Hill, and the painters Sir Noel and Waller Paton. One wonders what the ingenious David Paton might have become had he been born later into an age of opportunity.

NOTES AND SOURCES

(Copyright Declaration: Items marked * are reproduced with the agreement of On Fife Archives (Dunfermline Local Studies) on behalf of Fife Council. In this connection, I acknowledge the help given by the staff in the Reading Room at Dunfermline Carnegie Library and Galleries, DCLG). I also appreciate the support of Cat Berry and Allan Lennie who are descended by many generations from two of David Paton`s sons, Joseph Neil (1797-1874) and John (1794-1876), respectively.

-

Henderson, Dr. Ebenezer, Annals of Dunfermline, Glasgow 1879, p. 652

-

The witnesses at David Paton`s baptism were David Hutton and James Wardlaw, weavers in Dunfermline. The children born to John Paton and Agnes Deans were: Margaret (1765), David (1766), John and Robert, twins (1772), another Robert (1775), Mary 1778 and another John (1783). Some of the children appeared to have died in infancy.

-

Because M and W are often mistaken in old records, Margaret was also known as Miller or Willer. David and Margaret`s children were Elizabeth (Betsy), born April 1772; John, June 1794; Joseph (later Joseph Neil), June 1797, and David, Feb. 1800.

-

David and Catherine`s children were Mary, born April 1814; Agnes, Oct. 1816, and Neil, April 1819.

-

Dunfermline Burgh Council Minutes (Council Minutes), March 10 1792, National Record Office (NRS), Edinburgh, B20/13/13, p. 19. Daniel Thomsen, The Weavers` Craft, Paisley, 1903, pp. 256, 296. Caution is needed when referring to David Paton as there was another weaver of that name in Dunfermline at this time.

-

Council Minutes, NRS, B20/12/15, Jan. 3 1809, April 29 1809, June 7 1809. When he became Town Officer David`s wage was probably about £8 a year. As drummer he got tips at New Year and 1s. for going through the town on other occasions. M. Norgate, `By tuck of drum` (pamphlet), 1973. For the Volunteers, Henderson, op. cit, pp.553-4. The Magistrates were the senior councillors, i.e. the Provost, Bailies and Dean Of Guild

-

Pittencrieff `New Town` in a letter from Thomas Macbean, Dunfermline, to David Birrell, Edinburgh, August 5 1813, in *“Daniel Thomson, `Anent Dunfermline`, Vol. 1, Items 337, 381 (Volume 1 of 9 volumes held at DCLG).

-

W.T. Barr, For a Web Begun, Edinburgh, 1947, pp. 134-5. Alex. Stewart, Reminiscences of Dunfermline Sixty Years Ago, Edinburgh, 1886, pp. 129-30.

-

Henderson, op. cit, pp. 652-3.

-

Ibid. Benjamin Franklin`s mechanical harmonicon played music on glass. J. M. Mackie, `David Paton` in *`Dunfermline Men of Mark`, Vol.7, pp. 30-38, printed from a series in Mackie`s Dunfermline Journal, January 1 1909, p.7.

-

Henderson, op. cit, p. 569.

-

D. Patton, *`The History of Dunfermline`, pp. preface, 9-10, 15-16 and passim.

-

Henderson, op. cit, p.582.

-

D. Patton, *`A Dialogue betuixt the old and New Burgar Kirk of Dunfermline` (`Dialogue`}, 1st edition, 1811`, p. 35, passim. The Rev. John Campbell was ordained to the Old Lichts Kirk, Canmore Street, in September 1806 and died aged 28 in 1810.

-

D. Patton, *`Dialogue`, 3rd edition, preface.

-

Ibid, postscript, pp 80, 83, 89-90, 97-8, 106.

-

Ibid, p. 53.

-

Henderson, op. cit, p.608.

-

*`Anent Dunfermline`, Vol. 2, Item 729, 806.

-

`The Patons`,*`Anent Dunfermline`, Vol. 9, Item 387. The same was apparently the case with a biography of David`s son, Joseph Neil Paton, who died in 1874 (St. Andrews Gazette and Fifeshire News, June 20 1874.