Amelia Robertson Paton

Dunfermline’s “Famous Lady of Sculpture.”

By George Robertson, FSAScot.

The names of Dunfermline born Sir Joseph Noel Paton (1821-1901) and that of his brother, Waller Hugh Paton (1828-1895), are widely known and their fame as artists cannot be questioned. However, the name of their older sister, Amelia Robertson Paton, is not so well known despite the fact she also was an accomplished artist and sculptor. The fact she is not well known is surprising especially when it is considered she is responsible for a number of well-known statues, including those of David Livingstone, which stands proudly in Princes Street Gardens, Edinburgh, and Robert Burns, erected in Church Place, Dumfries. In view of this and in an effort to bring Amelia to the notice of a wider audience, we will now take a look at the story of her life.

Amelia was born In the Paton family home at Wooer’s Alley, Damside Street, Dunfermline, and the Old Parish Register for Dunfermline records this took place on 15th January, 1821, her name being recorded as Emmilia McDermaid (sic) Paton. (1) She was the eldest in a family of seven children born to Joseph Neil Paton (1797-1874), and his wife Catherine McDiarmid (1792-1853), the other children being named Joseph Noel, Jemima, Archibald, Waller Hugh, Catherine and Alexa. Only four of the children survived into adulthood, Archibald, Catherine and Alexa having died in childhood. Their father, Joseph Neil, who was a pattern designer preparing designs for the local linen factories, was also a Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, elected Fellow in 1846, and was very interested in local and national history. (2) He was a collector of many historical artefacts, including items from Dunfermline Palace and Loch Leven Castle, collected by him over many years, and which he proudly displayed in a museum he set up in one of the rooms of the Wooer’s Alley house. What Catherine thought of the museum being set up in the house is not recorded!

Catherine’s parents were Archibald McDiarmid and Amelia Robertson, she, according to the Ancestry.com website, being born to the couple on 13th July, 1792, at Mill of Invervack, Blair Atholl. This is further confirmed by an examination of the Old Parish Registers for Canongate, Edinburgh for the year 1819, which gives the information that Catherine, on her marriage to Joseph on 23rd September of that year, stated she was the daughter of the late Archibald McDiarmid, Farmer, Parish of Blair Atholl, Perthshire. Catherine was reputed to enjoy relating her Robertson family history to her children, stating she was connected, through her mother Amelia, to the Chiefs of Clan Robertson of Struan. This does appear to be the case as Amelia was the daughter of Robert “Rob Ban” Robertson of Invervack. Nancy Foy Cameron in her booklet Robertsons of Atholl, published in 1993, clearly states that it is from one of Rob Ban’s sons, Duncan, who was Amelia’s half-brother, that the present Chiefs of the Clan have descended.

Having discussed Amelia’s antecedents, let us now look at her early life in Dunfermline and we are fortunate that this was described for us by Amelia in an article written for The Young Woman Journal, published in August, 1895. Under the heading – “A Famous Lady Sculptor” – Amelia gave her interviewer – Sarah A. Tooley – the following description of her early days in the town –

“I lived a very romantic life as a child, near the old city of Dunfermline. Our house, in Wooer’s Alley, was in the midst of lovely scenery, a very retired spot, embowered in trees, situated on the top of the hill, close to the Royal Palace of Dunfermline and the grey ruins of the Abbey. My parents were Quakers, and I and my brothers and sisters were brought up very much alone, and allowed to roam about as we liked. This made us take to dreaming I expect. I was just a wild creature in those early days, climbing trees and playing quoits with my brother. I was passionately fond of outdoor life, of animals and plants. I remember making my first aquarium in an old stone coffin in the garden, one of my father’s antiquarian collection. It was his hobby to collect relics from the old palaces of Scotland, in fact, our home was like a museum. The drawing-room was called the antique room. It had suits of armour, chairs from Loch Leven Castle, and a number of interesting relics. Then we had Queen Mary’s cradle and James the Sixth’s bed.”

Sarah Tooley goes on to tell us Amelia showed her a beautiful miniature painting of her mother, stating – “ It was the first thing I ever drew and I had no previous training beyond the fact that all my life I had been accustomed to see my father sketching, and my brother Noel too. But in those days it was not thought necessary to give girls special training in drawing and painting. It was when I was twelve year old that I determined to try and paint a miniature of my dear mother.”

The miniature painting of Amelia’s mother Catherine impressed Sarah Tooley, who could not believe it had been done by a girl of twelve, especially one who had never been taught to draw. It would seem at this time, Amelia was continually sketching, in particular heads, but soon her attention turned to modelling in clay. She told Sarah Tooley her first tools were an ivory crochet-needle and a knife but eventually she was able to borrow better tools – from a plasterer! These tools must have inspired Amelia to further her new found modelling talent, she explaining to her interviewer –

“The first thing which led me to model was Mrs. Shelley – (Mary Shelley, 1797-1851) – sending my brother Noel a bust of her husband – (Percy Bysshe Shelley, 1792-1822) – which Mrs Leigh Hunt, -(Marianne Leigh Hunt, 1788-1857) – had done from memory, saying that she thought it bore a resemblance to Noel. I had been studying phrenology at the time, and when I saw the bust I said ‘she has not given Shelley a poet’s brain’, and I told Noel I could make a better bust of him than that. ‘I daresay you have audacity enough to try,’ he said, and I determined that I would. A man from Edinburgh came to cast the first bust. He was a little Italian and I remember what an event it was when he arrived at Wooer’s Alley with the stucco on his back. After I had modelled the bust of Noel, he came to cast it, and when he saw the bust, he put up his two hands and said, ‘Dis is quite de Apollo.’” Praise indeed from the little Italian, but, as Noel said, what audacity – from one so young!

Unfortunately, around this time, Amelia became quite ill, suffering from a severe case of bronchitis and this resulted in her being unable to work for some months. However, she slowly improved and began to become interested in her studies but, as Sarah Tooley says, ‘only in a desultory way, for in those days very little encouragement or opportunity was given to girls to enter upon a professional career.’ This of course, is an example of the attitude of the time toward girls and women having a career of their own.

The 1851 census for Dunfermline reveals Amelia was still living in Wooer’s Alley with her parents and brothers. However, two years later Amelia experienced great upheaval in her family circumstances when, on 17th June of that year, her brother Joseph married Margaret Gourlay Ferrier (3), the couple moving to Edinburgh to live. This was followed three weeks later when on 9th July, her beloved mother died. A further change took place some five years later when her father remarried, his bride being Catherine Mitchell, of Dunfermline. The marriage took place on 18th October, 1858. (5) How long Amelia remained in the family home is unclear but the 1861 census for Edinburgh shows she, and her younger brother Waller Hugh, were then living with their brother Joseph and his wife Margaret at 33 George Square, Edinburgh. One of the great advantages of Amelia’s move to Edinburgh was, for the first time, she had a studio of her own which allowed her to begin to work in a serious manner as a sculptor.

Financial security came Amelia’s way during October, 1861 when she became a beneficiary of the will of James Kerr of Middlebank, near Dunfermline, who bequeathed her the sum of £300 – worth around £36,630 today. It is thought this came about due to the fact James Kerr’s wife, Christina Pearson, was sister to Margaret Pearson the wife of Alexander Ferrier, they being the parents of Margaret Gourlay Ferrier, who had married Amelia’s brother Joseph. (6)

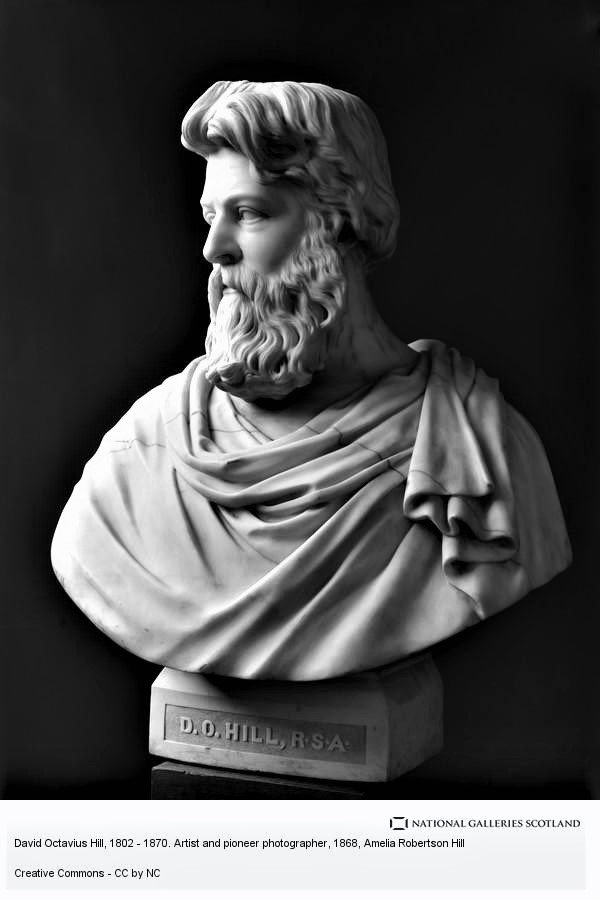

In addition to having two very talented brothers, Amelia married David Octavius Hill (1802-1870) on 18th November, 1862, (7) he being well known as one of the early pioneers of photography and also a talented artist. At the time of her marriage, Amelia was 40 years of age whilst her husband was eighteen years her senior. Amelia was his second wife. Having been surrounded by such talent and no doubt encouragement and, when this is added to her own obvious ability, it is perhaps no surprise she was able to surmount the obstacles which would have come her way during the middle and latter part of the 19th century, at a time when women were not usually encouraged to be successful.

In her interview with Sarah Tooley, Amelia gives us an idea of her early sculptural work when she states this included busts of John Fergus of Kirkcaldy, who was M.P. for Fife for 25 years, the Countess of Elgin and Thomas Carlyle. Amelia revealed many other people sat for her and for a time she devoted herself to modelling busts. However, her husband and her brother Joseph Noel, convinced her she had the ability to “do a statue” and she determined to do just that. One of the first completed was that of David Livingstone, the explorer, which today is considered one of her finest works. Amelia informed Tooley she modelled the Livingstone statue in secrecy, not even telling her brother Joseph Noel she was doing so, which must have been difficult as Livingstone actually sat for Amelia during the modelling, he doing this just prior to leaving the country for his final journey to Africa. In 1869 the completed the model was taken to London where it was displayed in the New Rooms of the Royal Academy, the art critics who viewed it considering it to be the most striking work of art exhibited that year. Today the full size statue can be seen standing in Princes Street Gardens. Edinburgh, alongside the Sir Walter Scott monument, having been unveiled on 15th August, 1876. Coincidently, three of the statues which adorn the Scott Monument were sculpted by Amelia, they being Magnus Troil, Monna Troil and Richard the Lionheart, each a character from Scott’s novels. On page 139 of her book “Genteel Mavericks”, Shannon Hunter Hurtado tells us Amelia travelled to Fontevraud, France, to model the head and crown of Richard from his tomb effigy

In addition to being known as a sculptor, Amelia was also a talented artist and revealed to Tooley that a painting, which her husband had begun twenty five years prior to their marriage, was, at that time, still unfinished. The painting depicted the historic scene when the representatives of the Free Church of Scotland met on 23rd May, 1843, to sign the Act of Separation and Deed of Demission from the Church of Scotland. Amelia states the painting showed over four hundred signees and it was her husband’s intention to show the face of each as accurately as possible. To do this he enlisted the assistance of another early pioneer of photography, Robert Adamson (1821-1848), and between them, the two men produced calotype images of the faces of those ministers involved in the signing. Amelia admits she began to work on the painting by putting in shirt fronts and collars, this being carried out during the early morning before her husband was out of bed. It was not long before she became more adventurous and began to paint in the actual faces and eventually, by working together the painting was at last completed to her husband’s satisfaction. During 1866 it was hung in the Free Presbytery Hall on the Mound in Edinburgh, where it still hangs to this day.

Unfortunately, Amelia’s marriage to David proved to be short lived as, having been in poor health for some time, on 17th May, 1870, he died at their home at Newington Lodge, Mayfield Terrace, Edinburgh. His funeral procession to Dean Cemetery, comprised a hearse drawn by four horses, sixteen mourning coaches and about a dozen private coaches. His coffin was mounted in gilt and on a massive plate in the centre of the lid was engraved his name and date of death. A bronze bust of David, sculpted by Amelia, was later placed on his gravestone. (8)

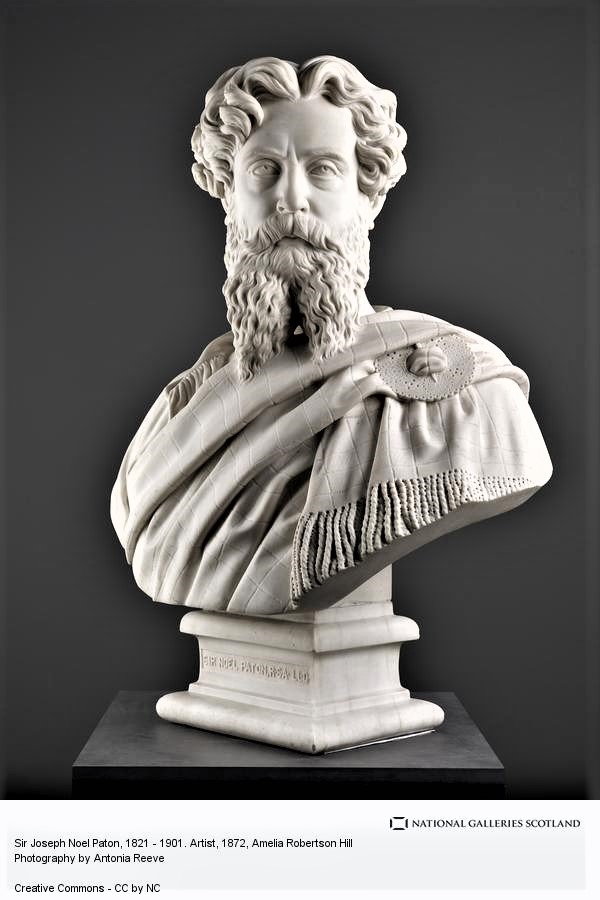

As the 1871 census for Edinburgh shows, Amelia continued to live at Newington Lodge after the death of her husband, the census recording she had living with her a 24 year old housekeeper named Christina McGlashan, who hailed from Blair Atholl. Amelia continued with her sculpting, completing busts of various people including one of her late husband and another of her brother Sir Joseph Noel Paton who, in 1866, had been appointed Limner for Scotland and knighted the following year by Queen Victoria. Another was commissioned by Dunfermline born Andrew Carnegie, who had Amelia create a bust of his mother Margaret Carnegie.

It is worth commenting on the fact that at this stage in her life Amelia is now being recognised as an accomplished sculptor, however, no doubt due to the previously mentioned outdated attitudes of the time she, having applied to become a member of the Royal Scottish Academy, was denied membership. Not to be thwarted, she assisted in the formation of an alternative Arts Society named the Albert Institute. The Society opened its doors to its members during 1877, holding meetings in their premises in Shandwick Place, Edinburgh, where artists were welcomed, regardless of gender.

A glance at the1881 census for Edinburgh tells us Amelia is still living at Newington Lodge but her household has greatly increased. Apart from five servants, her sister Jemima Roxburgh is living with her. Jemima, who had been the wife of Andrew Roxburgh, a shawl manufacturer and pattern designer, was now a widow her husband having died at Shipley, Yorkshire, on Friday 10th January, 1868. (9)

To return once more to Sarah Tooley’s interview with Amelia we learn she had been a life-long admirer of Scotland’s national poet Robert Burns. This resulted in her creating a statue of the poet which she submitted for consideration when it was proposed a statue of him should be raised in Dumfries. This was accepted and was used as the model for the statue which still stands today in Dumfries, it having been unveiled by the Earl of Rosebery in the spring of 1882. Tooley states the Burns statue was the last important piece of work executed by Amelia. The model for the statue which was erected in Dumfries, was originally placed in the City Chambers, Dunfermline, (10) but is now on display in Dunfermline’s Carnegie Library.

The 1891 census for Edinburgh, and that of 1901, show Amelia still living at Newington Lodge with her sister Jemima, with the latter’s daughter Josephine – usually referred to by her middle name Maud – also living with the sisters at the Lodge. In both census’ Amelia is recorded as being a retired sculptor, whilst Jemima and Maud are shown to be living on their own means. It is worth noting Maud followed in the footsteps of her Paton uncles and aunt by developing an artistic ability, this amply demonstrated in the book entitled Children’s Wild Flowers, Their Legends and Stories, which was beautifully illustrated by Maud. The book was written by Mrs Miller Maxwell and published in 1904.

When Amelia decided to retire is unclear but as Sarah Tooley tells us, she “has never ceased to model, and may yet be seen sitting at one end of the dining-room, with her tools spread out on a long narrow table, and a piece of wax-cloth put on the floor to catch the bits.”

Amelia died at Newington Lodge on 5th July, 1904 and was buried alongside her husband at Dean Cemetery, Edinburgh. (11) In her will, details of which were reported in the Scotsman newspaper dated 12th July, 1904, Amelia names one of her executors as Andrew Carnegie of New York, this implying a friendship had developed between the two of them, which is not surprising since both originated in Dunfermline and Amelia had already sculpted a bust of Andrew’s mother. Carnegie was also a beneficiary of Amelia’s will, she gifting him an oil painting by her brother Joseph Noel, entitled “Sons of God and the Daughters of Men”. In addition, Amelia bequeathed to the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, to be placed in the Scottish National Museum of Antiquities, Edinburgh, two small cabinets obtained from Loch Leven Castle and three items, believed to be helmets, plus two Etruscan necklaces, claimed to be of great antiquity, which Amelia stated had been brought by her from Rome, this being evidence she had at some time, travelled to Italy. These items are still in the possession of the National Museum, but are currently not on display. A further recipient of the will was the Scottish National Portrait Gallery which was gifted a portrait of her late husband by Robert Scott Lauder, RSA, (1803-1869), plus the busts of her husband and her brother Joseph Noel. (12) The painting and the busts can be viewed in the Portrait Gallery. Amelia’s estate was valued at £541, which, according to the Office of National Statistics, would today be worth around £69,000.

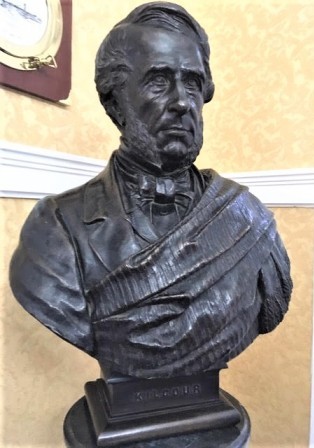

On display in Dunfermline are two works by Amelia, the first a bronze bust of Alexander Kilgour, (1800-1865), is on display in the downstairs chamber/atrium of Dunfermline City Chambers. Kilgour was Town Clerk of Dunfermline from 1849 until his death in 1865, and, in 1881 Amelia was commissioned by a number of local business men to create the bust as a mark of appreciation for the manner in which Kilgour had discharged his public duties whilst Town Clerk. (13)

The second is the previously mentioned bronze statuette of Robert Burns which was presented by Amelia to Dunfermline Town Council during 1881. Originally displayed in the City Chambers it was later moved to Dunfermline Carnegie Library and Galleries, where it is on display in the Queen Margaret Room. (14)

There is a third work in Dunfermline which I believe should be attributed to Amelia, this being the unsigned marble bust of Andrew Carnegie’s mother Margaret, which is also on display in Dunfermline Carnegie Library and Galleries. Although there is nothing on the bust to identify the sculptor, this writer believes it to be the previously mentioned marble bust of Margaret Carnegie which Amelia created, having been commissioned by Andrew to do so. This bust was exhibited twice, once in Edinburgh at the Royal Society Academy’s Annual Exhibition of 1881, (15) and two years later at the Annual Exhibition of Dunfermline Fine Art Association, (16) on both occasions identified as the property of Andrew Carnegie, and sculpted by Amelia. The bust was then observed by W.M. Gifford in Amelia’s home at Newington Lodge, Edinburgh in July, 1903, (17) this being the year prior to her death and it is presumed the bust was later moved to Skibo Castle by Andrew Carnegie. In 1932, Andrew’s widow Louise gifted the marble bust of Margaret Carnegie to Dunfermline Carnegie Trust (18) and it is this bust which is now on display in Dunfermline Carnegie Library and Galleries, presumably being the one Amelia was commissioned by Andrew to create.

Amelia was obviously a talented sculptor, her statue of Robert Burns in Dumfries and that of David Livingstone in Edinburgh being proof of this talent, but she was also a determined individual and an example of this is shown when she was denied admission to the Royal Scottish Academy she then became involved in the setting up of the alternative Albert Institute. Perhaps it is fitting that her interviewer Sarah Tooley should have the last word on the type of person Amelia really was when she says – “a more kindly, hospitable nature than Mrs Hill’s is not to be found, nor an artist so ready to give advice and encouragement to young beginners.”

References, notes and acknowledgements.

- Dunfermline OPR’s Ref. 424/120/79.

- Society of Antiquaries of Scotland – List of Society Fellows.

- Greenock Advertiser newspaper, 22nd June, 1859, p.3.

- Scottish Press newspaper, 15th July, 1853, p.7.

- Ancestry website, Select Marriages of Scotland, 1561-1910.

- See note below.

- Inverness Courier newspaper, 27th November, 1862, p.8.

- The Scotsman newspaper, 23rd May, 1870, p.2.

- The Scotsman newspaper, 14th January, 1868, p.4.

- The Journal Guide to Dunfermline, by J.B. Mackie, printed by the Journal Printing Works, St Margaret Street, Dunfermline, circa 1925, p.127.

- Dundee Evening Telegraph newspaper, 8th July, 1904, p.3.

- The Scotsman newspaper, 12th July, 1904, p 8.

- The Daily Review (Edinburgh) newspaper, Tuesday, 13th December, 1881, p.3.

- Dundee Advertiser, newspaper, Friday, 7th October, 1881, p.6.

- The Royal Scottish Academy Exhibitors, 1826-1990, Vol. 2, (E-K).

- Dunfermline Fine Art Association Catalogue, 1883, pp 53-54.

- Dunfermline Press newspaper, Saturday, 25th July, 1903.

- Edinburgh Evening News newspaper, 30th September, 1932, p.12.

Regarding reference number six, the connection between the Paton/Ferrier/Kerr families came to light whilst preparing my article entitled The Story of Middlebank House and some of its Occupants, which appeared in The Scottish Local History Journal, published in February, 2012 – Issue 82, pp 38-41.

For further reading on Amelia, the previously mentioned book “Genteel Mavericks – Professional Women Sculptors in Victorian Britain”, by Shannon Hunter Hurtado, published in 2012 by Peter Lang, Berne, Switzerland, is recommended.

Whilst preparing this article, I am most grateful for the assistance received from the following people – Margaret Maitland, Principal Curator of The Ancient Mediterranean Department of World Culture and Stephen Jackson, Senior Curator Furniture and Woodwork, both National Museum of Scotland, Edinburgh. Alejandro Basterrechea, Image Licensing Assistant, National Galleries of Scotland, Edinburgh. Robin H. Rodger, Royal Scottish Academy of Art and Architecture, Collections Department, Edinburgh. Jade Dent, Fellowship and Events Officer, Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, Edinburgh. Stewart Coupar, Senior Library Assistant, A.K. Bell Library, Perth. Sharron McColl, Local Studies Supervisor, OnFife Archives at Dunfermline Carnegie Library and Galleries, Dunfermline. Jennifer Jones. Co-manager, Andrew Carnegie Birthplace Museum, Dunfermline. Finally, I would like to make particular mention of Cat Berry, Founder of the Amelia Trail and close family member of the Paton’s of Dunfermline, who provided me with much information regarding Amelia, which was gratefully received.