“PRISON – WHIT PRISON?”

By George Robertson

DID YOU KNOW….

that there was a prison in Dunfermline until 1950?

Take a walk down Dunfermline High Street today and ask anyone where Dunfermline Prison was and it is almost certain, in the majority of cases, you will be met with a shrug of the shoulders, a blank look and the reply – “Prison – whit prison?” Perhaps the reply is to be expected since the prison referred to, having been in use for over 100 years, ceased to exist around 50 years ago. Having established that there was a prison, the questions to be answered now are why was there a prison in Dunfermline and where was it situated.

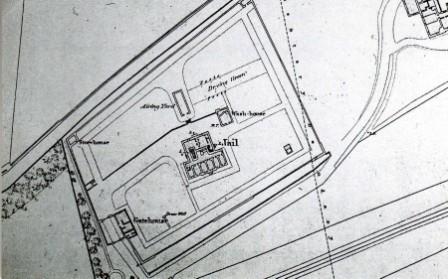

The 1839 Prison Act was the culmination of much agitation by Prison Reformers such as Elizabeth Fry, who wished to see an improvement in the conditions under which prisoners were held. Dunfermline was no exception to this necessary improvement as prisoners were kept in the Old Town House, the forerunner of our current City Chambers, under conditions which were probably no better than anywhere else in the country and consequently, in the early 1840’s work began on a new prison in what is now Leys Park Road. The architect for the building was Thomas Brown, Jnr., of Edinburgh, who had been appointed Architect to the Prison Board of Scotland during 1838. By January 1845, the prison building work had been completed at a cost of approximately £2070 and by the end of the year it had housed 262 prisoners, all serving short sentences.

The Dunfermline Press of 20th February 1981 gives a detailed description of the prison. It consisted of three floors each having six cells intended to house criminal prisoners, twelve for men and six for women. These cells were well ventilated and heated by flues. In addition there were two commodious cells, with fireplaces, for civil prisoners and three apartments for the jailer and matron. There were three long corridors for exercising and the two acre site which was enclosed within a boundary wall had a prisoner airing court, also surrounded by a wall, and a two storey gatehouse for prisoner reception. Initially the prisoners slept in hammocks but at some later date wooden beds were provided. There is no doubt conditions did improve for the prisoners from 1839 at which time their separation by means of individual cells was introduced. This enabled each prisoner his or her own privacy, which was a vast improvement to the overcrowded conditions experienced prior to the 1839 Act. However, another reason for the introduction of separation was to keep the younger prisoner from being influenced by the older more experienced prisoner but it should be kept in mind that isolation in a cell, being denied the conversation of other prisoners and the hard labour which was endured by the prisoner was not the ideal solution. Having said that, during those early days prison food may have had some effect on prisoner morale as a typical menu was porridge for breakfast, barley broth and wheaten bread for the mid-day meal then potatoes and milk for supper.

It should be pointed out at this stage that the religious and educational needs of the prisoners were catered for. However, in the case of the former, perhaps the quality of the incumbent could be questioned. During the early days of the prison, two ministers were being interviewed in Dunfermline for the position of prison chaplain. One was chosen, a decision not meeting with the approval of a certain James Inglis. He was a local manufacturer and compatriot of Andrew Carnegie’s grandfather Thomas Morrison – and obviously just as outspoken. When the decision was made he was heard to remark – “weel-a-weel, the man preached his kirk empty, I only hope he will preach the jail empty too.” Another well known name in Dunfermline was Robert Martin, who was Andrew Carnegie’s teacher prior to the Carnegie family leaving for America. Again, during those early days, Martin was working in the prison, attempting to educate the prisoners.

An examination of the 1851 Census shows that the Governor of the Prison at that time was Thomas Gillespie. His wife Janet was Matron. John Aitken was the Prison Officer and his wife Margaret was Gatekeeper. On the night of the Census the prison housed two civil and fifteen criminal prisoners comprising eleven males and four females. The youngest prisoner was from Charlestown. He was 14 years old. The oldest was a 63 year old woman, born in Fossoway. One unexpected revelation was the fact that one of the other female prisoners, a hawker, gave her birthplace as Calcutta, India.

Normally, prisoners in Dunfermline Prison had committed crimes of a fairly minor nature but in 1852 a man was held there whilst under sentence of death for murder. He was an Englishman named Charles Fancoat who on 18th February, 1852 was sentenced to death at Perth High Court for stabbing a man to death in Dunfermline four days earlier – justice was obviously a much swifter process in those days! He was then transferred to Dunfermline Prison where he was to be executed by hanging on 25th May. However, a petition was organised and the death sentence was commuted to life imprisonment and transportation to Australia. Fancoat is the last person known to have been incarcerated in Dunfermline Prison whilst under sentence of death.

When the Census of 1871 was taken it revealed the previous prison staff had been replaced. William Napier was now Prison Governor and his wife Elizabeth was Matron. Thomas Hunter was Prison Warder but there was no indication on the Census that his wife was employed as Gatekeeper, a position which appears to have been dispensed with. No female prisoners are recorded but eleven male prisoners are listed. Nine of these stated they were born in and around the Dunfermline area whilst one was born in Ireland. Surprisingly, the other was a sailor named Johan Klein – born in Prussia!

The County prison system, which had been in use since 1839, was brought to an end with the implementation of the 1877 Prison Act which brought about the nationalisation of prisons. This meant all local prisons in the United Kingdom, including Dunfermline, were brought under the control of central government, thus removing the responsibility previously undertaken by the local authority.

In 1881, for the first time, the road leading to the prison is given a name – Cemetery Road – as it also led to the new cemetery which had been opened for interments on 31st July, 1863. This gave some cause for wry amusement since the Poorhouse, opened in July, 1843 was situated adjacent to the prison and therefore the road could be described as an example of the final journey – from prison – to poorhouse – to cemetery. The road is nowadays known as Leys Park Road and still gives access to the cemetery.

By 1891 the post of Prison Governor was no more. The Census of that year shows the prison in the charge of a Police Sergeant, assisted by a Police Constable, the latter residing in the gatehouse. The fact that both these officers were over 60 years old, together with the fact there were no other members of staff referred to, would indicate the prison no longer served such an important function as previously. The Census shows the prison held eight prisoners, all male, six of whom were general labourers, and the others being a cutler and a photographer. Only one gave his birthplace as Dunfermline whilst the others stated they had been born in Edinburgh, Glasgow, Perth, Ireland and three in England.

From around this time the story of the prison is one of gradual decline. In 1883 its function had been changed to the status of Legalised Police Cells for the detention of prisoners for up to 14 days and the control of the prison returned to the Local Authority. Legalised Cells are peculiar to Scotland and were intended for the imprisonment of short term prisoners. Nowadays, prisoners can be held in these cells for up to 30 days.

During May 1891, due to the retirement of the Police Constable, it was decided the accommodation should be restricted to six cells. The wisdom of this decision can be seen in the Census of 1901 which shows the prison held only one prisoner, an Irish born tailor, whose jailor was a Police Constable. During July 1949 a further decision was made that the building should no longer be used as a Legalised Cells unit and the final closure as a prison came the following year, on 31st October 1950, it having been purchased by Dunfermline Town Council for the princely sum of £1,850. From then until demolition took place the building was used by the Council’s Lighting Department and then by Dunfermline District Council’s Property and Works and Direct Labour Department. Finally, during February 1981, the demolition workers moved in and began to dismantle the main building but leaving the boundary wall and gatehouse intact.

The above article originally appeared on page 9 of “Bygone Dunfermline 2007”, published by Dunfermline Press newspaper.

An enlarged version of the article appeared in the 2008 Spring edition of the Scottish Local History Journal – pages 36 to 40.

Charles Fancoat photo courtesy of the family. Other photos courtesy of Dunfermline Press.