`YE MURDERER OF HER OWNE CHILD`

by Dr. Jean Barclay

In 1709 Janet Mitchell, who was about 28 years old and worked as a servant maid for John Watt in Sunnyside, Saline, was tried in Dunfermline and hanged for the murder of her new-born child (1). The case rested on an `Act anent murdering of Children` 1690 which attempted to suppress the prevalent crime of child murder. Under this severe act, a woman did not have to physically kill her child but if she concealed her pregnancy or did not call for assistance at the birth and the child was found dead or missing, she was held `ye Murderer of her owne Child` even if there was no wound or bruise on the body. Any woman found guilty in the terms of this act was to be punished with `the pains of death` and `escheat of her moveables` (confiscation of her property) (2). While the act may have helped to reduce child murder there seems little doubt that many innocent women were unjustly accused and executed or banished. This was arguably the case with Janet Mitchell.

On May 15th 1709 the Saline kirk session led by the Rev. Patrick Plenderleith, met to consider a report that Janet Mitchell was guilty of fornication and had been found to have milk in her breast, a sign that she was with child or had given birth. When questioned, Janet confessed to fornication with James Gibson, a fellow servant at Sunnyside, but would not say whether she had had a child or not and it was decided that members of the session and some women should go to Sunnyside the next morning to make enquiries. And, having been informed that Janet had been at her sister`s house in Muckhart Parish between Sabbath and Wednesday last, Mr. Plenderleith agreed to write to Mr Ure the minister there to enquire about her behaviour in her sister`s family (3).

The minister, two elders and four women including a midwife duly went to Sunnyside where they heard Janet acknowledge that on the evening of Sabbath May 8th she was on her way from Saline to her sister`s in Muckhart when in the fields alone she travelled (laboured) and gave birth to a male child, who was dead. She also confessed that she told no-one about it and nor did she call for assistance but shortly afterwards buried the child near the place of his birth. She was willing to go and fetch the child to be seen at the Church of Saline and two elders and her master John Watt went along with her. The child was brought to the church where it was inspected by midwives, who declared that the child was more-or-less full-term in appearance and had no wound or bruise upon his body. Janet was further interrogated by the session if there was any life in the child at the birth and she answered none to her knowledge. Considering this `weighty affair`, the session read the act of parliament anent murdering of children and sent an express to the Justices of the Peace and the Magistrates of Dunfermline to inform them of this emergency. They ordered Janet to be secured and the dead child to be kept for further inspection.

On Tuesday May 17th the minister reported that the Justices of Dunfermline had ordered the constables to apprehend Janet and to bring her to their prison, there to remain at her own expense, or that of the session at Saline, until the trial for her alleged crime. The dead child was again produced and inspected before several witnesses and he was then coffined and buried. Janet was present all the time and was exhorted and seriously charged in the Lord to repentance through Grace. As there was no security for her in Saline Parish, she was remitted to the constables to travel the four miles to Dunfermline along with two of the Saline elders to see her delivered off their hands. The session were obliged to give bond for Janet`s sustenance during her abode in Dunfermline as she was unable to maintain herself.

On May 18th Mr. Plenderleith reported that he had met the Justices of the Peace about Janet`s maintenance in the laigh (low) prison in Dunfermline Tolbooth and had prepared a letter about the alleged crime for session to approve. Mr James Gibb, their clerk, was to go over express with it to the Queen`s Advocate in Edinburgh. The minister had agreed with James Meldrum, merchant in Dunfermline, to supply Janet`s provisions. It had cost the session £3-10s. in expenses for the express to the Queen`s Advocate, £1 for her security and provision in Saline the night she was taken and now they had to pay for her food. In the interest of the `poor`s money, the session hoped to recoup some of their outlay and, after Mr. Robert Syme, one of Janet`s old masters, had given them details about several of her debtors, they decided to advertise that the money owing should come to them and not to Janet. The minister produced a letter from Mr. Ure of Muckhart stating that Janet`s sister in his parish knew nothing of her guilt.

Now the session turned its attention to James Gibson, named as the father of the dead child. On May 20th he confessed to fornication with Janet Mitchell and `the grievous scandal thereof was held forth to him with its heinous aggravations`. James denied having any hand in the alleged murder of the child, of which he had never been accused by Janet. Session found James `ignorant` and dealt seriously with him, then appointed him to make his first public appearance for rebuke before the congregation on the next Sabbath. On May 23rd it was reported that James had appeared as ordered and gave some appearance of repentance.

On the same day John Edward, elder, reported that he had spoken to the four persons indebted to Janet Mitchell and they promised to be careful with the money that they owed her. Mr James Gibb reported his diligence in going to the Queen`s Advocate at Edinburgh, Sir James Stewart, with information about Janet Mitchell and her circumstances, and Sir James had sent an order to the Magistrates of Dunfermline to have her transported over to Edinburgh tollbooth so that her alleged crime might be tried there.

On May 29th the Saline session considered that they would be put to much expense for Janet Mitchell`s maintenance while she continued at Dunfermline. They delayed James Gibson`s next public appearance until there was further evidence of his being more sensible of his sin.

On Tuesday June 28th Janet was still in Dunfermline prison awaiting transfer to Edinburgh, but the Baillies of the Regality Court of Dunfermline felt that, as Janet had been a servant in Nether Kinnedar ground, which was within their jurisdiction, they were empowered to judge her and resolved to do so notwithstanding the order sent by the Queen`s Advocate that the trial would be in Edinburgh.

Having obtained permission to try Janet in Dunfermline, John Couper, procurator fiscal of the Regality Court of Dunfermline, applied to the Lords Justice in Edinburgh for letters of authority to summon witnesses who lived `outwith the Jurisdiction of the said Regality` so that they could be examined in the Tolbooth of Dunfermline. Any witnesses refusing to appear could be fined 100 merks (4).

Janet`s trial at the Regality Court of Dunfermline was held in the Tolbooth of Dunfermline on Friday July 22nd 1709. The judges were Robert Ged junior of Baldridge, his depute John Moubray of Cockcairny, who were depute baillies to Charles, Lord Hay of Yester, hereditary Baillie and Justice of the Regality Court. The case against Janet Mitchell was pursued by John Couper, and her procurator was Alexander Barclay, writer (5).

After a preamble referring to the law of God and the law of the land against murder, particularly the 1690, the trial began. Evidence pointed to Janet`s guilt or lybell and unless she had `reasonable cause to the contrair` she would be executed.

John Coupar, procurator fiscal for the Court of Regality, produced three executions or orders he had issued, one for Janet Mitchell, the accused or pannell to compear (appear before a legal body), one for witnesses in the trial and the third for 45 men from whom the 15 members of the assyse or jury would be selected (6). By the second order, the witnesses were to be Agnes Gibson, spouse to Andrew Anderson, in Bickramside, John Watt in Norther Kinnedar (Sunnyside), William Reid indweller in Burnside, Thomas Kirk, portioner of Sheardrum, Colin Oliphant, brother to David Oliphant in Over Kinnedar and George Mudie in Killerney. According to the third order, the 45 potential jurymen were obliged to compear or would be fined 100 merks.

Janet Mitchell now compeared with her procurator, Alexander Barclay, writer in Dunfermline. The assyse was called and named and Janet confirmed she had no objection to any of the jurors. Alexander Barclay raised two minor objections before claming that Janet should be indemnified under a recently passed Act of Indemnity, but, on behalf of the Court, John Coupar dismissed the objections, and declared that indemnity under the Act was only allowed for crimes committed before a certain date and Janet`s alleged crime came after this (7).

The judges therefore proceeded to probation (the hearing of evidence) and the witnesses were one by one solemnly sworn, purged and interrogated. Some of the witnesses could not write and had their testimony signed by Robert Ged. Agnes Gibson, midwife, aged 50 years or so, deponed that she knew the pannell to be a green (young) woman who had had confessed to her that she had given birth and she, the deponent, had handed the dead baby boy in at the porch door of Saline Church, dressed it and taken it to a grave.

John Watt, a married man aged 27 or so and Janet`s present master, deponed that he was present when Janet acknowledge she had brought forth a child and with others went along with her until she said `go no further, the child is here`. He saw her take it out of the side of a sandy knowe (mound) – it had dirt on it and was naked. He then saw her bring it to Saline Kirk and Agnes Gibson dress it. He further deponed that in the middle of April he challenged her if she was with child as she was so big and she told him `it did not become him to know`. She had a deal of clothes about her and made excuses about a sore arm and the cold weather.

William Reid, a kirk elder, who was married and aged 46 or so, said much the same as John Watt, but added that she had twice denied the birth before session, but had owned the child to be hers when she took it out of the hole. Thomas Kirk, married and aged 34 or so, said much the same but added that as she brought the child to be buried, Janet said `I`ll bring the child myself, it is my own bairn`. Colin Oliphant aged 40 or so said that he was in Saline church when he heard the minister ask James Gray to bring in the dead child but he refused and he heard the pannell say she would bring it herself as it was hers. George Mudie, aged 30 or so, had nothing new to add.

Alexander Barclay made further efforts on Janet`s behalf, claiming firstly that the witnesses did not agree to May 8th as the date of the crime and because of this Janet could still claim the benefit of the Act of Indemnity, and secondly that Janet`s confessions heard by the witnesses were `extrajudicial, which is but a hearsay` so that their testimonies could not militate against her. After further questioning of two of the witnesses who confirmed that it was in May when they heard Janet`s confession, Barclay`s protests were dismissed and the trial proceeded.

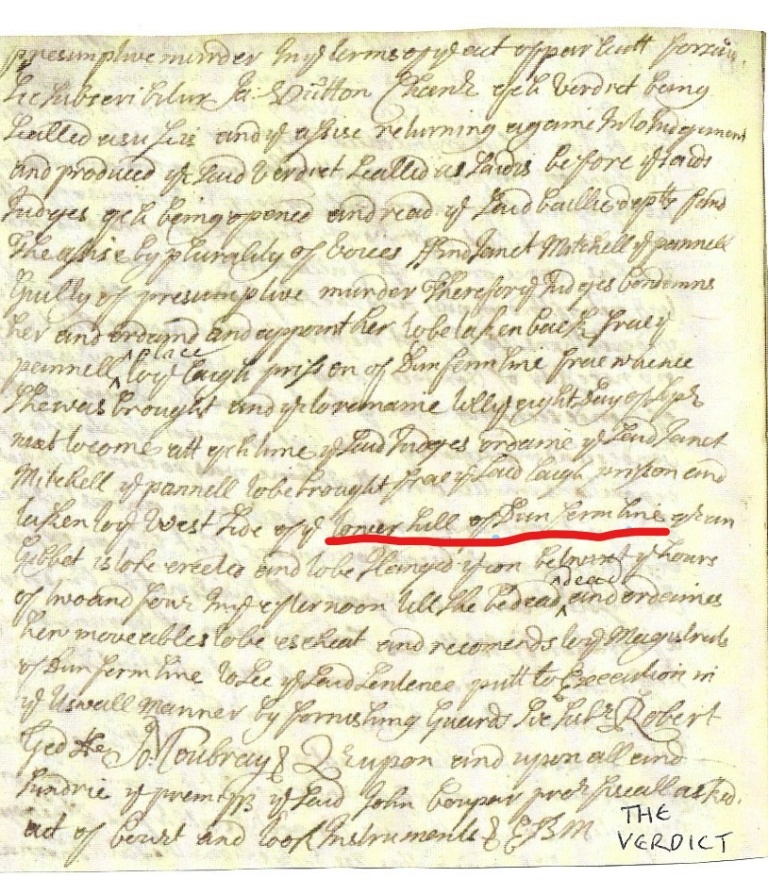

On the judges` order, the assysers enclosed themselves in the council house in the Tolbooth and by a plurality of voices elected John Scot as their clerk and James Hutton as their chancellor or foreman. Having considered the whole case, the act of parliament and the witness statements, `ye assyse by plurality of voices finds Janet Mitchell guilty of presumptive murder in ye terms of ye act of parliament forsaid`. The verdict was then recorded and sealed.

In the court room, the verdict was unsealed and read out. The judges formally condemned Janet and ordained that she be returned from the pannell place (dock) to the prison of Dunfermline where she would remain until Thursday, September 8th, when she would be brought to a gibbet erected on the west side of the tower hill of Dunfermline and there hanged between two and four in the afternoon till she was dead. The judges also ordained that her moveables be escheat and recommended that the magistrates (the Council provost and baillies) see the sentence put into execution and to provide a guard of militia men for the occasion (8).

The guard would have been needed because a hanging in Dunfermline was rare, especially of a woman, and would have attracted vast crowds. Janet`s execution probably followed the usual pattern. The gibbet consisting of an upright pole and crosspiece would have been set up earlier in the place of execution and she would have been taken in a cart or walked the short distance to the site. After she had addressed the crowd she would climb the ladder (usually of 13 steps) to the gibbet, the noose would be placed around her neck by the executioner sitting above her and he would push or `turn her over` from the ladder when she had given him a sign.

Janet was duly hanged on September 8th 1709 and after a time her body was cut down, carted to a crossroad near Yetts of Muckhart and buried (9). On September 11th the Saline session recorded that they had received a satisfying account of her death, `she having given some pleasant evidence of the Lord`s working fine Repentance in her`. They appointed James Gibson to be rebuked publicly a second time for his heinous scandal, which was accordingly done the Sabbath immediately after the execution. Nothing could be found about his being an accessory in the child`s death but the `heavy aggravations of his guilt` was laid forth before him which was affecting to the congregation and himself, according to his knowledge, but he was `very ignorant`. Session allowed £3-10s. to the jailers of Dunfermline prison on Janet Mitchell`s behalf which was otherwise wanting.

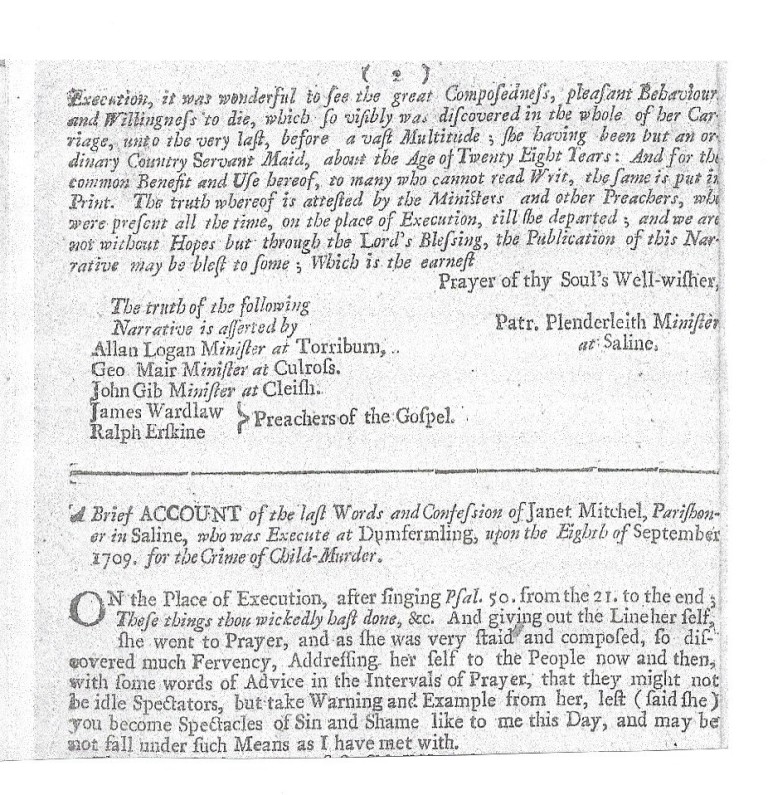

There is a curious postscript to this sad story. In 1764 a pamphlet of eight sides was published in Edinburgh entitled `A brief account of the last words and confession of Janet Mitchel, parishioner in Saline, who was execute at Dunfermling upon the Eighth of September 1709, for the crime of child-murder`.

The language in this narrative sounds too high-flown to be that of `an ordinary country serving maid` of mean education and other disadvantages but its truth as `the very same words as they dropt from her mouth` was affirmed by Patrick Plenderleith, Minister at Saline, Allan Logan, Minister at Torryburn, George Mair, minister at Culross, John Gib, Minister at Cleish and James Wardlaw and Ralph Erskine, Preachers of the Gospel, who were present at the place of execution to the end. The confession was put in print `for the common Benefit and Use hereof to many who cannot read Writ`. (10).

Janet`s address to the `vast multitude` who had come to witness her execution was published to show `an uncommon instance of the Lord`s wonderful rich and free grace in Christ towards some great sinners`, her calm, even contented, acceptance of her fate and as a warning to others. Janet told the crowd that she had kept her pregnancy hidden `because of the weary fee` and wanting to serve out her service to the term (11). She confessed that in the open fields on her way to Muckhart she had brought forth a living child but he died after she had carried him two or three miles and she had hidden him underground thinking the whole business was over. `O! what an Unnatural Mother was I, and justly deserves this death this day, for my Neglect and Carelessness of the poor Infant, tho` I did it through much Ignorance and Unskilfulness `. Janet said she had been kindly treated in prison and praised the ministers who had visited and prayed with her. She warned her hearers not to hide their sin, especially fornication and uncleanness, and added that she hoped some would be affected by her words though others, she knew, would `go away carelessly to Ale-houses`. She took a little refreshment, giving thanks for her last drink on earth, blessed the Lord to the very last, even to the foot of the ladder, and pleasantly took her farewell of the ministers and others with a smiling countenance. Going up the ladder, she said to the people `O take Warning now, Sirs, and pray much for me, for you know not what death you may die your selves`. Then she sang psalm 51 `Have mercy upon me, O God` and, kissing the Bible, gave it to her brother. She prayed for her minister and her parish and for the `poor, worthless wretch` who had been guilty with her that the scales of ignorance might fall from his eyes – `he is not free of this, tho` he come not to such an untimely Death as I have done`. Just before the end she was asked what sins now stared her in the face and she answered `The Bairn`. Finally, she gave the executioner a sign, saying `Into thy Hands I commend my Spirit`, was `turned over` and died.

Janet Mitchell`s hanging was the last execution of a woman in Dunfermline. Was she guilty? The law of the time said she was but that law no longer exists and hopefully, in view of her self-confessed `ignorance and unskilfulness`, she would be judged more leniently today.

Notes:

(The text has been considerably modernised from the original).

- Janet`s surname was also spelt Mitchel.

- The 21st Act, 2nd Session, of the 1st First Parliament of William and Mary, 1690. .

- Saline Kirk Session Minutes, National Records of Scotland (NRS) CH2/32/1, various dates.

- Coupar`s request to the Justices in Edinburgh, (NRS) JC/26/91/524.

- (NRS) RH11/27/23 Dunfermline Regality Court Decisions, pp.176-185.

- List of jurors: David Oliphant of Over Kinnedar, William Hunter in Dowielands, John Rolland tenant in Drumcapie, James Hutton tenant in Grange, John Anderson in Wester Gellets, Robert Couston in Stone, John Couston in Keirsbeath, Laurence Mudie tenant in Killerney, Henrie Fotheringham in Nether Kinnedar, Adam Turnbull portioner of Grange, John Henderson, tenant in Drymilne, Andrew Smith, portioner of North Fod, John Walls in Holl Baldridge, John Scott portioner of Mastertoun, and Thomas Mitchell tenant in Easter Gellets.

- The Act of Indemnity of 1709, in Queen Anne`s reign, was designed mainly to pardon (and pacify) Jacobites accused of crimes committed before April 19th 1709 following a rebellion against the crown in 1708. Alexander Barclay was possibly clutching at straws in trying to use it to indemnify Janet Mitchell.

- Why Tower Hill was chosen for the execution rather than the usual Town Hill or Witch Loan is not known (unless Tower and Town were muddled by the clerk). The Minutes of Dunfermline Burgh Council, Vol. 4, Sept. 6 1709 (NRS) B20/13/4 mention the guard being requested

- E. Henderson Annals of Dunfermline, Glasgow, 1879, p. 384. The name of the executioner is not mentioned but he was probably also the dempster or doomster who pronounced the `doom` of the prisoner.

- It is strange that the pamphlet was not published in Edinburgh until 1764 as the introduction states that `the same was put to print` and it is easy to assume that this was shortly after Janet`s death. Ralph Erskine and James Wardlaw were newly licensed by Dunfermline Presbytery to `preach the everlasting gospel` and were waiting to be called as ministers to a parish.

- The word `fee` could mean a servants wages paid at the end of their term, often six months. Janet may have lost her `weary` (troublesome) fee if her pregnancy was known.