Tales from the Kirk Session

by Dr. Jean Barclay

The Presbyterian Church of Scotland did not like Christmas and ensured that it was not celebrated in Scotland for some 400 years. The old winter festival of Yule had lasted 12 days and, Yule Day, as `Christmas Day`, continued to be recognised by the Catholic Church. After the Reformation of 1560, however, the founding fathers of the Church of Scotland had no time for `Christ’s mass` and other `popish` rites. In the Calvinistic First Book of Discipline, John Knox and others stated that any doctrine that `men by laws, councils or constitutions have imposed upon the consciences of men, without the express commandment of God’s word…and keeping of holy days of certain Saints commanded by men, such as be all those that the Papists have invented as the feasts (as they term them) of the Apostles, Martyrs, Virgins, of Christmas, Circumcision, Epiphany, Purification and other fond feasts of our Lady, because in God’s Scriptures they neither have commandment nor assurance, we judge them utterly to be abolished from this Realm: and affirming farther that obstinate maintainers and teachers of such abominations ought not to escape the punishment of the civil Magistrates`.

In 1573 the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland confirmed the abolishment of `all days that hereto have been kept holy except the Sabbath day, such as Yule day, saints days and such others` and in 1583 it forbade bakers from preparing Yule bread and mincemeat pies and ordered them to report anyone requesting them. (1)

However, people still attempted to cling to the old ways, especially in the early days of the Reformation. In December 1574, the kirk session of St. Nicholas, Aberdeen, admonished 14 women for `playing, dancing and singing filthy carols on Yule day`, and on December 26th 1583 the Glasgow Kirk Session sentenced five persons who had kept Yule to public repentance, that is to appear on the `black stool` in the kirk to be admonished by the minister in front of the congregation (2).

Some festivals were temporarily restored under Episcopalian rule and James VI reinstated Christmas in 1617, but the Scottish Kirk continued to resist it and attendance at church was scant.

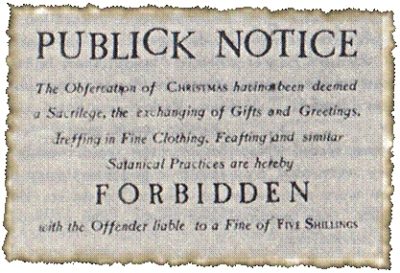

Puritans who emigrated to North America in the 1620s to escape persecution under the Catholic-leaning Stuarts took the opposition to Christmas with them, as can be seen from this poster from New England, which could just as easily apply to Scotland.

Puritans who emigrated to North America in the 1620s to escape persecution under the Catholic-leaning Stuarts took the opposition to Christmas with them, as can be seen from this poster from New England, which could just as easily apply to Scotland.

In 1638 the General Assembly reiterated the banning of Yule as a holiday and Parliament followed suit in an act of 1640 which stated that `keeping the Yule vacance has interrupted the cause of justice in this kingdom` and went on `the Kirk within this kingdom is now purged of all superstitious observation of days…therefore the said estates (parliament) have discharged (forbidden) and simply discharge the foresaid Yule vacance and all observation thereof in time coming`. Courts of justice now had to sit without interruption from November 1st to the end of February (3).

These edicts were passed down to the presbyteries (or parish courts) throughout Scotland and through them to the kirk sessions. The minutes of the kirk session of Dunfermline record that on December 15th 1640 the minister read out `the act of Presbyterie ordaining all persons to leave off their feasting, playing and riotous and wild living on yule day`.

In February 1645 the General Assembly prohibited masters of schools and colleges from granting Yule as a holiday, giving rise to `bar-the-door` days where masters were locked out of school or college by their pupils until the holiday was granted (4)

The kirk regarded December 25th as ordinary working day and punished backsliders. On January 29th 1650 the Dunfermline session summoned Bessie Coupar in Grange, Bessie Sands in Lymekills and William Malcolm in Mylnburn `for superstitious absenting from work on Yule day`. The three accused acknowledged their fault and, as it was their first lapse, were privately admonished by session, but premonished of `yr danger if they be fund so againe`, presumably a public rebuke.

Under Cromwell Christmas celebrations were banned but the restoration of Charles II in 1660 brought them back again, though not to Presbyterian Scotland. William and Mary, Protestant of course, took advice from the Scottish Parliament and in 1690 an `Act discharging the Yule Vacance`, re-iterating that of 1640, stated that `The king and queen’s majesties by the advice of the estates of parliament have discharged and simply discharge the forsaid Yule vacance with all custom and observation thereof`. This ban was officially repealed in 1712 but the Kirk continued to frown on Christmas observance, more from a religious than a social point of view (5).

The Presbyterian kirk’s dim view of Christmas continued for some four centuries but by the later-nineteenth century some churches – though not the Wee Frees – held Christmas services, even with carols, and Scottish people – perhaps influenced by Queen Victoria, Charles Dickens and what was happening in England – increasingly recognised Christmas as a festive occasion, especially for children. From the 1860s seasonal advertisements in the Dunfermline newspapers increased year by year. Typical was this advertisement of 1870 for `Moyes Furnishing and Fancy Repository`.

In 1871 came the Bank Holidays Act which made Christmas Day a Bank Holiday in Britain and it seemed as if change was afoot. In the Dunfermline Press of December 23rd 1871 a leading article entitled `Christmas` began `Old Father Christmas is again at our door` and went on to observe that `We in this land of Wishart and Knox, of `Confessions` and `Covenants` have not yet learned to welcome Christmas with the same warmth of feeling as our brethren in the sister country. But the day is not far distant, we believe, when this great national festival of the Church will be observed with equal honour on both sides of the Tweed` (6).

However, change did not happen overnight and Christmas remained low-key in Scotland with people still working on December 25th. This was revealed in a television programme (and book) of the late-1980s. Looking back to 1919 and his boyhood in rural Perthshire, a man recalled that, although the children might get fruit in their stockings, `We didn’t have a holiday on Christmas day, we went to school. It felt quite normal because work was going on in the farms and in the village; shops were working and, aye, the mills were working`. A woman recalled that `My father was a very strict Presbyterian and New Year was the only time you could hang your stocking. Christmas was the time to sing carols and go to church. No Christmas dinner, no Christmas pudding, it was like every other day of the week`, while another man remembered asking his Edinburgh grandmother why they did not celebrate Christmas like his friends, only to be told `We’re no heathens, laddie`, meaning Catholics or Sassanachs or both. This man felt he had discovered Christmas when serving in Italy during the Second World War and remarked `It was great – my granny was wrong!` (7).

After the war films like `It’s a Wonderful Life` and early television programmes showing Christmas jollity `down south` re-enforced the feel-good factor and change came fast. In 1958 Christmas became a public holiday in Scotland but this was apparently under common law and granting it seems to have been a matter for individual local authorities or companies (8) When it was introduced by Dunfermline Town Council in 1958, the building tradesmen working for Dunfermline Council did not even want it as it meant sacrificing a day from their three day New Year break. But the Council pointed out that most men wanted the day off and Corporation tenants did not want tradesmen working in their houses on Christmas Day (9). Having Christmas Day off was still noteworthy and the Aberdeen Evening Express for December 24th 1959 reported that `It will be almost like a Sunday at the commercial docks tomorrow. For the first time dockers and shipbrokers will be on holiday. It has been decided to fall in line with other ports and recognise Christmas Day as a holiday. Work will carry on as usual at the fish market which will be closed for two days at New Year, but most firms connected with the fishing industry will also try to finish early`. On December 25th 1959 under the heading `A holiday for 100,000 – Christmas break in Glasgow` The Scotsman observed `All shipyards and most engineering works in Clydeside and the Paisley thread mills will be recognising Christmas Day as a holiday` and a spokesman for John Brown stated that the decision had been made last year but this was the first time it would come into operation`.

Where Christmas Day was still not a holiday, workers increasingly took it off, sometimes sacrificing a day of their annual leave to do so. In 1968 newsagents and booksellers led petitions for change and in 1970 the Scottish MP Tam Dalyell promoted the cause in Parliament, declaring that `as a point of principle if not of belief, no-one in Scotland now wants to work on Christmas Day` (10). Christmas Day, although already a public holiday, was not officially a bank holiday but in 1971 the Banking and Financial Dealings Act regulated the system making Boxing Day an additional bank holiday in Scotland and New Year’s Day for the rest of Britain. The Scots like the English now had a two-day break at Christmas (10).

Christmas in Scotland has probably caught up with New Year as the main winter festival, certainly from a commercial point of view. No-one wants to be called a Calvinist or a grinch but sometimes when Santas, reindeer, Christmas trees and tinsel appear in October, and festive jingles resound in the shops for two or three months, it can seem as if the old Presbyterian fathers were not entirely wrong.

Notes and sources:

- `Christmas an illicit pleasure`, an exhibition at the National Records of Scotland (NRS), Edinburgh, December 2017. I am grateful for the help with details of the exhibition to Jocelyn Grant of the NRS. The Kirk nearly always referred to `Yule` rather than `Christmas`, possibly preferring a pagan to a `popish` word.

- NRS, see above.

- `Act discharging the Yule Vacance`, Records of the Parliament of Scotland (RPS) to 1707

- G. Weightman & S. Humphries, Christmas Past, London Weekend Television, 1988.

- Act Discharging the Yule Vacance, July 16th 1690, RPS.

- George Wishart, c.1513-1546, was a Scottish protestant reformer burned for heresy, who may have converted John Knox. The `confession` mentioned is not the Catholic rite but the Protestant `Confession of Faith` from Knox et al, First Book of Discipline`.

- Christmas Past, pp.18, 27, 29, 35.

- There are many references to Christmas becoming an official holiday in Scotland in 1958 but I have yet to find the legislation. See for example, W. D. Crump, The Christmas Encyclopedia, `in 1958 Scotland celebrates Christmas as a legal holiday for the first time since 1561`, Christmas Past, p. 37 and Martin Johnes, Christmas and the British, London, 2016.

- Dunfermline Council Records, December 11th 1958 (at the Carnegie Library and Galleries).

- NRS, op. cit.