Shopping for Clothes in Victorian Dunfermline

By Sue Mowat

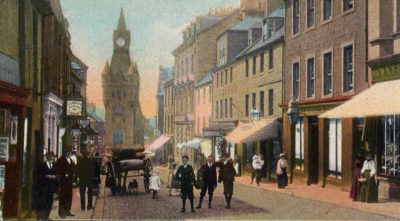

Setting out to buy clothes in Victorian Dunfermline there were so many possible outlets it’s hard to know where to start, but probably the best place is Bridge Street, home of seven of the town’s ten drapery shops. There were ‘clothiers’ in the town who sold ready-mades for gentlemen but if you wanted clothes with a really good fit you would choose your fabric at a draper’s shop and have it made up to your own measurements, by a tailor or dressmaker employed by the shop or by an independent worker.

The choice of fabrics was wide; for instance in the Spring of 1863 John Davie (8 Bridge Street) offered the ladies a typical stock of black and coloured silk for dresses, mantles and bonnets in Glaces, Gros de Naples, Chenes and Foulards. Other fabrics were Mohairs, French de Laines, French Merinoes, Lawns, Poplins, Poplinettes, Coburgs and Bareges ‘in new styles’. For the gentlemen there were Scotch Tweeds, Union Tweeds, Moleskins, Cords and Velveteens. Davie also advertised ‘Gentlemen’s Clothing, Children’s Kilt and Knickerbocker Dresses and Servants’ Liveries made to order’ and in the following year announced that millinery and dressmaking were now ‘done on the Premises in the Newest Style, under the management of a thoroughly experienced Milliner and Dressmaker’.

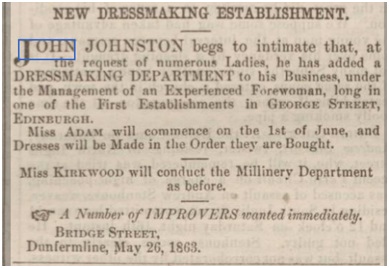

John Johnston (west end of Bridge St) catered specifically for ladies and in 1859 announced that he had fitted up the storey above his shop as a Millinery, Mantle and Shawl rooms under the superintendence of Miss Kirkwood, ‘ an Experienced Milliner from one of the most Fashionable Edinburgh Millinery Establishments’. A loose mantle or shawl was an important item in the wardrobe of a lady in the 1860s as this was the heyday of the crinoline, whose ‘silken balloon’ of a skirt could not be accommodated in a fitted coat, although a short waist-length jacket might be worn. In 1863 Johnston added a dressmaking department to his establishment.

John Johnston (west end of Bridge St) catered specifically for ladies and in 1859 announced that he had fitted up the storey above his shop as a Millinery, Mantle and Shawl rooms under the superintendence of Miss Kirkwood, ‘ an Experienced Milliner from one of the most Fashionable Edinburgh Millinery Establishments’. A loose mantle or shawl was an important item in the wardrobe of a lady in the 1860s as this was the heyday of the crinoline, whose ‘silken balloon’ of a skirt could not be accommodated in a fitted coat, although a short waist-length jacket might be worn. In 1863 Johnston added a dressmaking department to his establishment.

Johnstone’s big speciality, however, was ‘Family Mournings’. All drapers sold a variety of black dress fabrics but Johnston could supply practically everything necessary for a decent mourning outfit. In September 1862 he ‘greatly increased’ his Mournings department, offering nine different black fabrics at prices ranging from 8d to 7/6d a yard. He also had black Llama and Cashmere long shawls (10s to 29s each), black Grenadine square shawls for £1 and two kinds of black mantle cloths (3/4d to 9s a yard). Mourning caps and bonnets were made on the premises to order ‘on the shortest notice’, also mantles and jackets of the newest designs and any style – even in mourning it was important to be fashionable!

Dressmaking

What happened after a lady had bought her fabric (15 yards or more was needed to make a dress) depended on her circumstances. If she had the necessary skill she could sew her dress herself and by the 1860s sewing machines were available for those who could afford them, although a woman who could not afford to pay a dressmaker probably could not afford a sewing machine either, so she would have to do all the work by hand. Making the skirt was fairly simple, if laborious. It involved the stitching together of lengths of fabric, gathering them to fit the waist and sewing the hem. The ‘body’ (bodice) however, was a complex item comprising a number of shaped sections and in the absence of paper patterns it could only be cut out using an old bodice as a guide. Then there was the lining and the boning to be done and the sleeves to make and set in. All in all it was much easier to pay a dressmaker if you could possibly afford it. One indicator of the growing prosperity of Dunfermline during the nineteenth century is the number of dressmakers identified in the census records in relation to the size of the population. In 1841 there was one to every 200 inhabitants. By 1901 the ratio was one to every 90.

So who were all these dressmakers, and what made them turn to the trade? The basic motivation was the need to earn money but the reasons for this varied considerably and details of the 1861 Census return for Dunfermline shed some light on those reasons. In that year 98 women were identified as dressmakers. Nineteen of them, including four pairs of sisters, were helping to support a widowed mother (in three of these cases the family was also taking in lodgers). Twenty dressmakers were widows or unmarried women and forty-three were the daughters of small tradesmen who needed extra income. Of the tradesmen fathers, nine were weavers and there were also tailors, blacksmiths, grocers, shoemakers, a baker, a pawnbroker, a joiner, a mason, an upholsterer, a teacher and a wright. Some of these women may, of course, enjoyed their trade but it is noticeable that most of the younger ones were eventually ‘rescued’ by marriage and that those who continued to work had either remained single or had married men who were poor breadwinners.

Crinolines

The original crinoline was a stiff fabric, made of a combination of horsehair and cotton or linen, that was made into petticoats to hold out skirts into a bell shape. In 1856 Monsieur Milliet of Paris patented the cage crinoline, consisting of steel hoops of graduated sizes held together by vertical ribbons of strong braid.. Although steel was the best and most popular material for making crinoline hoops, whalebone and cane were also used. The advent of the cage crinoline allowed skirts to spread out to as much as six feet in diameter, although by the end of the 1860s they were reducing in size and they disappeared altogether during the next decade.

One reason for the popularity of the crinoline cage with women was explained by an aunt of Charles Darwin’s granddaughter Gwen, who wrote a memoir of her Cambridge childhood of the turn of the 19th/20th century. Her aunt explained that the cage produced a sensation of lightness and freedom after years of being encumbered by the multiple layers of as many as six petticoats that were necessary to produce the required skirt shape.

Crinolines were much less popular with the gentlemen, who were literally kept at arm’s length by the spreading skirts. The editor of the Dunfermline Press was definitely not a fan and often published satirical articles about them, along with more sombre accounts of ladies who had been burnt to death when their skirts got too close to a fire.

The Gentlemen

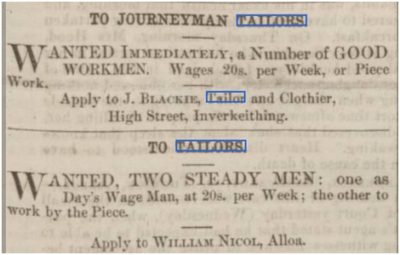

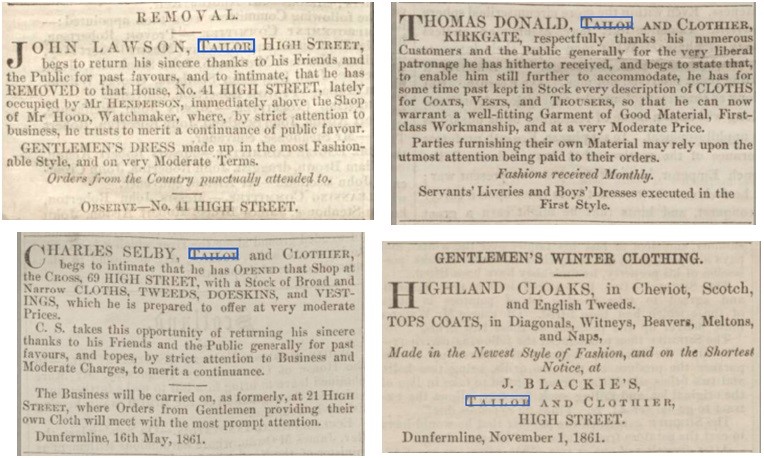

After a gentleman had bought his fabric he invariably turned to a tailor to make it up, either leaving it with the draper’s men or employing an independent worker. The 1861 Census lists eleven ‘master tailors’ who employed men and apprentices and many of whom had shops in the town. There were also 50 journeymen or fully qualified tailors and fourteen apprentices. Tailoring seems to have been a rather peripatetic trade and half the men named in the Census were not natives of Dunfermline. Most came from other places in Fife or from Edinburgh, but there were also four Englishmen, two Irish and one who had been born in Malta. Of course, other tradesmen included non-natives among their ranks, but the number of ‘outsider’ tailors was particularly high. This tradition may have stemmed from the practice in previous centuries, when tailors worked in their customers’ homes and usually travelled around the countryside to visit farms and villages.

Most drapers and clothiers employed any number between two and ten men so most of the 50 journeymen probably worked in the various shops. A few of the apprentices were working for their fathers but most were probably also being trained by shop owners. Some advertisements mentioned the wages paid to tailors –

Some journeymen operated independently –

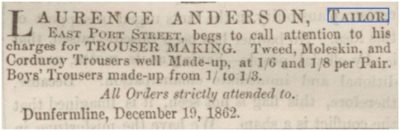

Laurence Anderson quoted some prices –

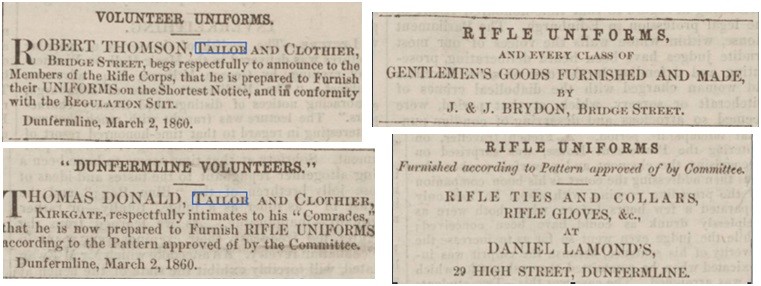

The formation of the Dunfermline Volunteer Rifle Corps in November 1859, with 120 members, provided an opportunity for local tailors that they were quick to seize.

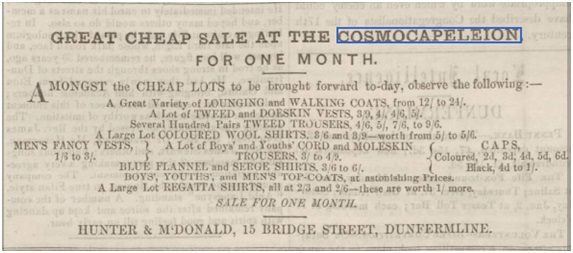

The Cosmocapeleion

Some drapers and tailors stocked ready-made coats and suits for gentlemen, but for the largest and cheapest selection the place to go was the Cosmocapeleion at number 15 Bridge Street. This was one of a small chain of shops that originated when a Mr Levy set up as a draper on Edinburgh’s South Bridge. He wanted an impressive name for his shop and being acquainted with James Donaldson (then a student but eventually Sir James, Principal of the United College of St Andrews) he asked him for a suggestion and Donaldson fabricated this Greek word, meaning ‘World Shop’ or ‘Universal Provider’. The Bridge Street shop was taken over from AM Levy by Hunter and McDonald in 1861, by which time there were also branches in Perth and Dundee. By 1875 the Dunfermline shop had disappeared from the town’s Valuation Roll.

The Cosmocapeleion advertised profusely, always emphasising the cheapness of its goods and often announcing the arrival of large stocks of a particular item. The two adverts below are just a representative sample of the many placed in the Dunfermline Press and the Saturday Press. The shop catered for the working man, with its ‘PLOUGHMENS’ and MECHANICS’ CLOTHING’, its ‘COLOURED WOOL SHIRTS’ and ‘BLUE FLANNEL and SERGE SHIRTS’. The ‘vests’ mentioned in the adverts were, of course, waistcoats, in tweed, doeskin, and black and coloured cloth. There were fancy vests too, but what was special about ‘Marriage Vests’? (see first advertisement).

The Cosmocapeleion also advertised classy-sounding items like ‘Shooting Coats’ and ‘Dress Suits’ but the prices betray their lack of quality. The ‘Regatta Shirts’ of the second advert were informal lightweight shirts that were introduced in the mid-19th century, according to the English Dictionary.

Babies and Children

Babies and Children

The younger generation were not forgotten, although there were only two establishments in the 1860s that catered specifically for them.

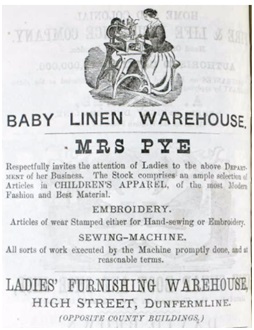

Jane Pye was a farmer’s daughter, born Jane Brown in 1834. In about 1859 she married Henry Pye, Sheriff Clerk Depute of Fife at Cupar and they started a family. Their marriage, however, was short-lived as Henry died of dysentery in October 1865, leaving Jane to support three small daughters and a new-born son. Henry had left a modest estate of about £280 with which Jane was able to stock a shop in Chalmers Street, opposite the church that was demolished in the 1970s to make the entrance to the Chalmers Street car park.

In December 1865 Mrs Pye advertised the opening of her shop in the Dunfermline Saturday Press, selling hosiery and baby linen and ‘LADIES and CHILDREN’S UNDERCLOTHING of every description’. In June 1866 she moved to the High Street, opposite the County Buildings (Old Guildhall) where she kept a shop for some years. By 1878 she had left Dunfermline, presumably for Perth, where she is found in the 1891 Census. She died there in 1916 at the age of 82.

Ann Rankine, a shoemaker’s daughter, married a miller, Thomas Houston, at Monimail in 1850. This was another short-lived marriage; Thomas Houston died of erysipelas at Iron Mill, Dalkeith in 1862. He only left Ann £91 17/2d but this was sufficient for her to stock a shop in Bridge Street ‘immediately opposite Milne’s Hotel’ (the City Hotel), which opened in November 1862. Her advertisement was plainer than Jane Pye’s but was far more informative about her stock.

A month after opening she was advertising the arrival of new stock which included ‘A large variety of DRESS CAPS from 1/11d upwards. BABIES UNDERCLOTHING, PINAFORES, LINEN CAPS &c on equally favourable terms’.

Unlike Jane Pye, Ann Houston stayed in Dunfermline for the rest of her life, dying of pneumonia at Bridge Street in 1890. Her daughter Janet took over the shop and ran it until about 1900.

Boots and Shoes

Boots and Shoes

The 1861 Dunfermline Directory listed 20 boot and shoe makers, all but five of them working in the town centre. The best source of information about their wares and prices is the advertisements in the local press for the Dunfermline shop of the chain belonging to the Newcastle shoemaker George Handyside. In 1861 he was selling Wellington Boots at 7/6d – 8/6d, short Wellingtons at 6/9d – 7/6d, Bluchers at 5/6d to 5/10d and Ladies’ Balmoral Boots at 4s – 5/6d.

Wellington Boots were not, of course, the rubber ‘wellies’ of today but leather boots made in a style named after the Iron Duke, the victor of Waterloo. The other men’s style was named after General Blucher, whose Prussian troops had turned the tide at Waterloo in favour of the British army. The derivation of the Balmoral boots needs no explanation. All these styles were rivetted and Handyside announced that he had bought the secret of a mixture of metals that produced tougher rivets which enabled him ‘to maintain as much superiority in the manufacture of rivetted Boots and Shoes as he has long had in the sewed work.’ The advertisement added that all Handyside’s shops were now ‘well stocked with Sewed Boots and Shoes, which have given so much satisfaction and rendered them famous throughout all Scotland’. Later advertisements drew attention to ‘Gentlemen’s Clampt Elastic-Side Boots with splendid Levant tops and durable calf galoshes at 9s and 9/6d and ‘Ladies Clampt Elastic Boots’ with pure silk elastic.

The most successful local shoemaker was Andrew Carnegie’s uncle, the fiery Radical Thomas Morrison, who employed more than 20 men and boys. He had two shops, initially one in Bruce Street to which he later added no 6 High Street. By the 1860s Morrison had handed over the running of the shops to his sons Robert and William and was concentrating on his public duties as a Town Councillor (since 1834) and ultimately as a bailie.

Morrison shared his Bruce Street shop with another shoemaker, John Brown, who moved to a different shop in Bruce Street when Morrison’s was taken over by his sons. His establishment was modest, employing two men and a boy, but his sons David and John went on to make their names in a different field. In the 1870s David opened a dye works in Grieve St which was soon converted into the Westfield Laundry and which operated until after World War Two. More recently, the building was for many years the showroom of Magnet Kitchens, but it was demolished in late 2017.

Another David Brown specialised in cheap boots and shoes for working people, most of them made by himself and two or three employees. He had set up in business in 1864 at the age of 20 at number 39 High Street and frequently advertised in the local press, always emphasising the cheapness of his wares. The 1881 census gives his occupation as ‘master bootmaker’ but when he died in 1886 he was living at Jamestown, Inverkeithing, which suggests that his boot-making was not prospering and that he had gone to work on the new Forth Railway Bridge, whose builders lived in a lodging house at Jamestown. The cause of death, ‘abscess on knee’ suggests a neglected industrial injury. He certainly left no money and his widow survived by taking in washing. She died in 1901 of a pathetic combination of maladies, ‘cardiac debility 6 years, gastric catarrh & pneumonia 3 months, gallstones and inanition 2 months’ and finally, ‘exhaustion 1 month’.

Brown was the surname of a number of Dunfermline shoemakers, none of whom seem to have been related, except for Alexander Brown and his son James. To confuse matters even further there were three other shoemakers called James Brown and one is worth mentioning for a reason unconnected with shoemaking. He was originally from Dysart, lived in Monastery Street and was moderately prosperous, employing three men. He managed to give his only child, Janet, a good education and in 1858 she opened a highly-regarded seminary for girls and small boys, initially teaching in the Mason’s Hall in Schoolend Street and moving to Chalmers Street in 1864. She and her assistant, Isabella Scotland, a grocer’s daughter, taught the basic three Rs, together with French, Bible history, Needlework and Geography – the excellence of her pupils’ map-drawing was particularly noted when the school was examined. In 1869 Janet married the widowed William Dick, master of Dunbar Grammar School, and one of her sons, Stewart Dick, became a well-known author on artistic and historical subjects in the early 20th century. His grandfather James Brown died in 1866 and a modest low stone marks his grave at the western end of Dunfermline Abbey Churchyard.

Thomas Buchanan, with a shop in Chalmers Street, was probably the most commercially successful of the Dunfermline shoemakers. His rise and eventual decline are evident from the number of his employees recorded in the Census returns – 1851 15 men, 1861 26 men and 9 boys, 1871 28 men and 1 boy, 1881 6 men and 1 boy. He retired in 1887 and in the same year was elected to the Town Council. Rather than indicating any lack of success, the reduction in his staff reflects his lessening reliance on business for an income. By the time he died in 1896 he owned property in Pittencrieff Street, Chalmers Street, Carnegie Street and Golfdrum. He also held several mortgages and his estate (excluding the value of property) amounted to almost £2000. In his will he left his two properties in Pittencrieff Street to his daughter Janet, who had kept house for him after the death of his wife.

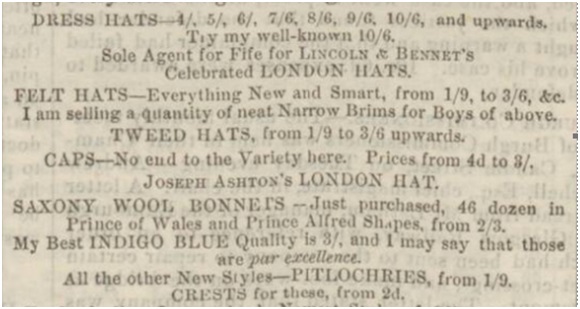

Hats and Bonnets

No respectable Victorian, and hardly any un-respectable ones, would venture out of doors without some kind of head covering. Drapers sold a variety of hats for gentlemen. John Davie of Bridge St, for instance, advertised ‘SILK and SATIN HATS including the Prince of Wales and other shapes, CLOTH and TWEED CAPS in Great Variety’. However, for the widest choice of styles and prices the place to go was Robert Nicol’s hat shop in the High Street.

Mr Nicol also catered for babies and children and his stock included shirt collars, scarves, ties and braces. He had started in business in 1837 and was the founder of Robert Nicol gents outfitters which, after several changes of family ownership, was still trading in Chalmers Street in 1989.

Mr Nicol also catered for babies and children and his stock included shirt collars, scarves, ties and braces. He had started in business in 1837 and was the founder of Robert Nicol gents outfitters which, after several changes of family ownership, was still trading in Chalmers Street in 1989.

Milliners

A lady who needed a new bonnet or hat might visit a draper, who sold both the finished article and basic shapes with the necessary ribbons, feathers, flowers and other trimmings for those who preferred to concoct their own confections. However, not all women were able or willing to trim their own bonnets and hats and, as with dressmakers, the number of milliners and straw hat makers grew over the years. In 1851 there were 17 but by 1881 the number had risen to 40. Some drapers employed their own milliners, but there were quite a number of freelancers as well.

Milliners had to keep up with the latest fashions, because a woman who could not afford a complete up-to-date outfit would often give herself a new look with a hat or bonnet in the latest style. Henry Syme, a local weaver and poet who often commented on mundane matters, wrote of changes in fashion in his poem ‘When I Was a Lassie’.

The young folk’s gaun gyte wi’ their pride an’ freegaries

There’s nae Megs an’ Marys, they’re a’ misses noo;

In silken balloons they gang trippin’ like fairies.

Wi’ butterflee bannets far up off their broo.

When I was a lassie, oor bannets were modest,

They measured twa feet ower the snoot tae the croon,

But thae new French fashions tae me seem the oddest

That e’ere were inventit by limmer or loon.

The poem seems to have been written in the 1860s, when the brims of bonnets had receded to show the forehead and part of the hair. The poem contrasts them with the poke bonnets of the 1830s, which buried the wearer’s face within an enormous blinkering brim and had an extended crown to accommodate the high topknot hairstyles of the period. Bonnets continued to diminish in size throughout the century and hats became increasingly important.

The Dunfermline Press sometimes printed fashion notes and here is an excerpt from an issue of August 1861.

Several new bonnets have appeared within the last few days. Among prettiest is one of white crinoline, lined with light blue silk and trimmed with a tuft of blue feathers, fixed by a tea rose. A fancy straw bonnet for demi-toilette is trimmed with a plisse a la vieille of silk of two different shades of green and on one side a bouquet of flowers. A bonnet of Belgian straw has the front trimmed with three plaitings of blue ribbon. On the left side there is a bouquet of blue chrysanthemums and the same flowers are intermingled with the under trimming. A much-admired Leghorn bonnet is ornamented with a tuft of red cornflowers and wheat ears. The strings consist of white ribbon, figured in a pattern of ears. One or two bonnets, composed of straw and French chip, have been very effectively trimmed with peacocks’ feathers, the blue feathers from the neck and breast of the bird being tastefully blended with the richly-variegated tail-feathers.

It is unlikely that many Dunfermline ladies could get any further than dreaming of such exotic Paris concoctions but perhaps some might get an old bonnet brought up to date with a blue chrysanthemum or a bunch of red cornflowers or even a peacock’s feather.

Of the thirteen milliners listed in the 1861 census but not in 1871, six had married (one of them in Australia) two had switched to dressmaking, one was from Dalry and had moved back home, one had given up all work, a pair of sisters were running a boarding house and one whole family disappeared completely from the record and had probably emigrated. Two of the six who had married thereby ensured very prosperous futures for themselves. Jane Crombie, milliner and daughter of a Golfdrum Street grocer, married Gilbert Rae who became a major manufacturer of aerated water (fizzy drinks). Another grocer’s daughter, this time from Beveridgewell, married Robert Nicol, the hatter. Of the other three who married in Dunfermline, one wed a slater, one a cabinet maker and one a tenter (power loom mechanic).

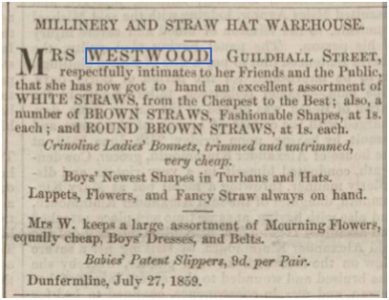

Of the four milliners who were mentioned in both the 1861 and 1871 census returns, the crown must go to Isabella Westwood who made a great success of her business, which she ran until she retired. She was born Isabella Richardson, the daughter of a baker who had died by the time of the 1841 Census, when Isabella and her mother, Margaret Philp, were living in Guildhall Street. They were very poor; Margaret took in washing and Isabella was making straw hats. Rescue was on the way, however, in the form of William Westwood, a weaver who lived in St Catherine’s Wynd. William and Isabella were married in June 1842 and William moved into the Guildhall Street house. Their first child was born in 1844 and named Adam, after William’s father. In 1858 came John and in 1860 Isabella, who seems to have died young.

Of the four milliners who were mentioned in both the 1861 and 1871 census returns, the crown must go to Isabella Westwood who made a great success of her business, which she ran until she retired. She was born Isabella Richardson, the daughter of a baker who had died by the time of the 1841 Census, when Isabella and her mother, Margaret Philp, were living in Guildhall Street. They were very poor; Margaret took in washing and Isabella was making straw hats. Rescue was on the way, however, in the form of William Westwood, a weaver who lived in St Catherine’s Wynd. William and Isabella were married in June 1842 and William moved into the Guildhall Street house. Their first child was born in 1844 and named Adam, after William’s father. In 1858 came John and in 1860 Isabella, who seems to have died young.

Isabella’s advertisement in the Dunfermline Press of 28 July 1859 reveals the extent of her millinery stock and also that she had branched out into selling children’s clothes. Isabella’s eldest son Adam, later to become well-known as a prolific artist, trained as a glass stainer and left home early. At the age of 17 he was lodging in Edinburgh and by 1871, now married to Janet Flockhart, had moved to Dumbarton Road, Glasgow, where the couple’s three children, William, Isabella and Christina were born.

Meanwhile, back in Dunfermline, Isabella’s millinery business was going from strength to strength. By 1871 her husband had given up weaving in favour of running her shop and in the 1881 Census was firmly described as ‘draper’. By 1884, when the next advertisement appeared in the Dunfermline Saturday Press, Isabella was travelling regularly to London to buy stock.

Meanwhile, back in Dunfermline, Isabella’s millinery business was going from strength to strength. By 1871 her husband had given up weaving in favour of running her shop and in the 1881 Census was firmly described as ‘draper’. By 1884, when the next advertisement appeared in the Dunfermline Saturday Press, Isabella was travelling regularly to London to buy stock.

Isabella was still advertising in the local press in 1888 but by 1891 she and William had retired and were living at number 8 Albany Street, where William died on 22 June 1906 of cancer of the oesophagus. Isabella survived him by two and a half years, dying of bronchitis in January 1908. Although, like so many other women, Isabella had taken up an occupation out of dire necessity, she obviously carried on her business after her marriage because she gained great satisfaction from it. Her flair and creativity made her very successful in a long career as a milliner and there can be no doubt that Adam Westwood inherited his artistic ability from his mother. Her creations were ephemeral, his can still be enjoyed today, but in their own ways both contributed equally to the sum of human happiness.

More Accessories

Gloves were very important to the Victorians, both for warmth and for respectability. Ladies especially would never be seen in public without them. John Davie the draper stocked French, kid, silk and lisle thread gloves for ladies (along with cotton, merino and woollen hosiery) for summer wear. For winter there were kid, cashmere, cloth and Braganza gloves, lamb’s wool and Shetland knit underclothing and a variety of white and coloured Welsh, Yorkshire and Lancashire flannels, ‘suitable for all kinds of underclothing’. For extra warmth in winter Davie also sold fur muffs, boas, ties and cuffs in real and French sable, Danish sable, chinchilla and real and imitation ermine. Davie’s was also the place to go for ladies Morocco and Roan leather reticules (handbags).

Davie’s hardy gentlemen customers seem not to have required gloves, but they could be had from J & J Brydon, clothiers, in the High Street, along with handkerchiefs, neck cloths, scarves, neck ties, scarves, braces and mufflers.

Another accessory specifically for ladies was the cotton or linen cap that was worn indoors and under bonnets by all married women and by middle-aged and elderly single ones (a sign that they were well and truly ‘on the shelf’). Everyday caps were quite easy to make at home but ready-made dress caps could be bought from JJ Johnston at prices ranging from 2/6d to 14/6d. Johnston also stocked the inevitable mourning caps.

A Finishing Touch

A Finishing Touch

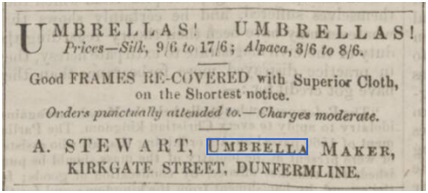

Drapers sold umbrellas and parasols but there were also two specialist suppliers in the town. They advertised as umbrella-makers, but umbrella-coverers would probably be a better description. The manufacture of umbrella and parasol frames was a specialised trade, so the Dunfermline ‘makers’ would have bought the frames and covered them with a variety of suitable fabrics. They also mended and re-covered old umbrellas and parasols.

Adam Stewart started business in Pittencrieff Street, where he and his family lived in a room and kitchen above his workshop and shop. In 1861 he moved to the Kirkgate ‘where he hopes by strict attention to orders to merit a continued share of public patronage’. He frequently advertised in the local press and his adverts (like this one from the Dunfermline Saturday Press in January 1867) make it clear that he specialised in re-covering frames as well as selling ready-made umbrellas. By 1880 he had branched out into selling spectacles, eye-glasses, field glasses and opera glasses.

In 1888 Stewart moved from his house in Douglas Street to a more modest shop and room at number 4 Randolph Street, commissioning William Clark (auctioneer and owner of the Music Hall) to sell off his surplus furniture and stock. He remained in Randolph Street until his retirement in 1895 when he moved back to the High Street, where he died in 1899.

In 1888 Stewart moved from his house in Douglas Street to a more modest shop and room at number 4 Randolph Street, commissioning William Clark (auctioneer and owner of the Music Hall) to sell off his surplus furniture and stock. He remained in Randolph Street until his retirement in 1895 when he moved back to the High Street, where he died in 1899.

Adam Stewart was fine if you wanted an umbrella, but a lady requiring a distinctive parasol would probably make for Marion Law’s shop in Abbot Street opposite the Commercial Bank (the façade of this Bank has been incorporated into the new Library/Museum building). A fashionable parasol was another way of updating an outfit relatively cheaply and it could be covered in fabric to match or tone with a dress. It might be quite plain or be frivolously trimmed with lace, fringing, ribbon, sequins or any other decoration that would not prevent it from being closed.

Marion Thomson/Law’s husband Robert had been an umbrella-maker and, until his death in 1856, the couple and their two small children lived in Guildhall Street. Robert left an estate of nearly £158 which no doubt helped Marion to carry on the business. Through her mother, Marion was the niece of Andrew Colville of Barnhill who died in January 1870 leaving her £300 in his will. Unfortunately this had not been paid by the time she too died in mid-March, but it would have been inherited by her children, James, a clerk in a Glasgow branch of the British Linen Company and Elizabeth, who moved to Edinburgh after her mother’s death.

Then And Now

The chief difference between buying clothes and accessories today and 150 years ago in Dunfermline was the comparative lack of ready-made clothing in the past. Another was the number of specialist shops. John Davie the draper, who also sold carpets and bedding, offered the nearest approach to a department store in the town, all the rest stuck strictly to their own particular sphere – boots from a shoemaker, hats from a hatter, bonnets from a milliner. There was not the immediate satisfaction of choosing from a rack of clothes of different sizes but on the other hand individual attention ensured a good fit and the chance to choose styles and ornamentation that made the outfit uniquely to your own taste.

Sources

The main source of information for this article was the British Newspaper Archive website, which holds the Dunfermline Press and Dunfermline Saturday Press for 1859 to 1867 and for some years in the 1880s and 1890s. The Census records were also very useful and Campbell’s Fife Traders, available in the Local Studies Library and as a CD from the Fife Family History Society, is an invaluable source of information about tradesmen and women of all kinds.