JOURNEYING INTO WHITE ROSE COUNTRY

The DHS Spring trip into North Yorkshire April 2017

by Lindsey Fowell

Heading across the Pennines along Route 66, our first stop was the magnificent Bowes Museum in Barnard Castle, Country Durham. A French Chateau-style, purpose built museum containing a vast and varied collection of European fine and decorative arts completed in 1892. The story of the museum is inseparable from the story of its two founders, John and Josephine Bowes. A Teesdale man, John Bowes traced his family roots back to the Norman invasion. The family wealth had grown on coal mining and shipping but, as he had been born out of wedlock, this English gent was shunned by high society even after his father married his mother on his deathbed. John inherited his father’s property but the title of 11th Earl of Strathmore passed to his uncle who became great-great grandfather to the future Queen Mother. After many years of enjoying the bohemian decadence of Parisian life, John eventually took the plunge in 1847 when he stood down from Parliament, moved to Paris and bought the fashionable Theatre des Varietes which still stands on the Boulevard Montmartre. One of its actresses charmed his attention and in 1852 John and Josephine Benoite Coffin-Chevalier (known by her stage name of Mademoiselle Delorme) married. As a wedding gift he bought her the Chateau du Barry just west of Paris which had once been a gift from Louis XV to his mistress. Eventually it was the sale of this chateau ten years later which funded the proposed museum at Barnard Castle. The resulting building is vast, grand and notably symmetrical, with countless tall windows and a glazed lantern roof to light the collections. In France it would not appear at all incongruous but in north-east England it trumpets itself as something quite distinct from its surroundings.

John had developed a keen interest in collecting art in the 1830’s but by the early 1860’s they were purchasing artworks and artefacts on a grand scale, above all paintings but also sculpture, prints, tapestries and embroideries, ceramics, glass, metalwork, furniture, textiles, clocks and watches, books and curiosities. Meanwhile, Josephine’s aspirations as a landscape painter had begun to emerge and she proved more talented in this sphere than she had been on stage with her work accepted for exhibition at the Paris Salon four years running. Their primary focus was always on European works and 80% of the collection is French. They employed a number of agents who encouraged the Bowes to be adventurous and to buy works that were not necessarily to their taste, which accounts for the presence of Spanish art and the two Goyas and El Greco, now among the Museum’s greatest treasures. These were purchased very cheaply at a time when they were not in fashion. Naturally all of this was costly, but the Bowes were relatively thrifty in their purchasing habits, buying most items for less than £10. In 1869 Josephine laid the foundation stone but sadly she would not see the Museum completed, nor would he. She died in February 1874 aged 49, John followed in October 1885. The grand opening of the Museum took place on 10 June 1892, a triumphant day marred only by the absence of the two people who had created it. The collection highlight is undoubtedly the Silver Swan, an extraordinary automaton which swims, preens itself, catches and eats a fish. Made by James Cox, silversmith in London in 1773 (with the mechanism invented by John Joseph Merlin) it was originally destined for the Far Eastern market but when this collapsed in 1775, Cox was forced to auction many of his “curiosities”. The original purchaser is unknown but it re-appeared at the Paris international Exhibition in 1867. It was the last purchase the Bowes made in 1872, just 2 years before Josephine’s death. Costing £200 it was the equivalent of 5 years wages for the working man at the time. It is still in working order and is as much admired today as it was 250 years ago.

Our base in Harrogate proved an ideal location from which to explore a little of North Yorkshire. The following day could not have been more different with our visit to the “Wonder of the North”, Fountains Abbey and Studley Royal Water Garden, the most complete Cistercian Abbey ruins in the country coupled with an elegant Georgian Water Garden and medieval deer park. It is one of the largest Abbey complexes within the UK and it is the sheer immensity of the buildings which strike a dramatic and lasting impression.

The Abbey story began in 1132 with signs of unrest at St Mary’s Benedictine Abbey in York. A group of 13 devout monks wanted to return to the simple teachings of St. Benedict, written down in the 6th century. The 13 fled York and came under the protection of the Archbishop of York whose lands included the valley of the River Skell to the west of Ripon, a place of quiet contemplation and inspiring beauty which he granted to the monks to start a new abbey. Life was so hard during the first winter that the monks almost gave up but in despair they wrote to Bernard, Abbot of Clairvaux in France to ask for help. With Rievaulx established as the first Cistercian abbey in Yorkshire Bernard was keen to support Fountains and by 1135 the future of the new abbey was secured within the Cistercian family. By the mid 1200’s Fountains had become one of the richest and most powerful religious houses in the country, with the sale of high quality wool the main source of its wealth. We learnt to our shame the marauding Scots had raided Fountains in the early 14th century when harvests were poor so the Abbey must have had an awesome reputation stretching far and wide. The monks also had to cope with a disastrous outbreak of murrain, an infectious disease of sheep and cattle which rendered the fleeces useless and the Abbey became indebted to the tune of £6000 (an enormous sum in those times) after gambling on the (fleece) futures market with their Antwerp agents. Then came the years of the Black Death in 1349-50 when around one third of the population, monks included, died of the plague. Despite a brief revival under influential and reforming Abbot Huby in the early 1500’s it was all to come to an untimely end. Henry VIII’s commissioners valued the Abbey at £1000 and in 1539 after 400 years of worship the Abbey fell victim to the Dissolution of the Monasteries. The only part of the complex to escape closure was the mill, as it brought in a valuable income for the estate. As a condition of sale the new owner a wealthy London merchant was obliged to make the abbey buildings unfit for religious use and the roofs were roughly pulled down, lead and glass stripped out and the Abbey’s assets, the mill and farms leased out to tenants.

William Aislabie bought Fountains Hall and the ruins of the Abbey in 1767. These adjoined the Studley Royal estate which he already owned, containing the Water Garden created by his father. When upkeep became too difficult the estate was taken on by the local County Council and the Abbey into state guardianship. The estate was acquired by the National Trust in 1983 with English Heritage maintaining the Abbey ruins. As early as 1718 work had started on the canals and cascades in the lower Skell valley. Over a hundred workmen dug and built the clean lines of a formal garden on the uneven valley floor. Together with elegant ornamental lakes, moon and crescent ponds, grottoes, tunnels and tumbling cascades the vistas and sight lines were designed to draw the visitor’s eye to classical follies and stone temples. Paths lead visitors today to the most spectacular outlooks culminating in the view of the Abbey. The significance of this 18th century pleasure garden was recognised in 1986 when it became only the twelfth World Heritage Site in the UK. UNESCO considers this landscape to be a feat of “human creative genius” which is one of the ten World heritage Site criteria.

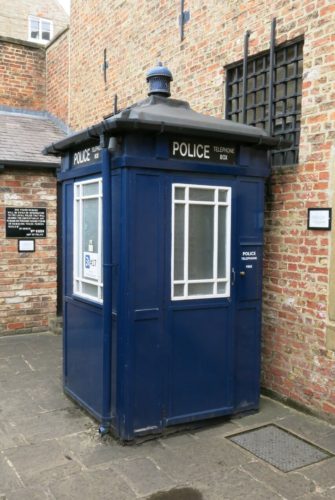

We returned to Ripon on our third day for a more leisurely exploration of this historic market town. In direct contrast to the elegance of the Water Garden the day before here we were plunged into the depths of human misery with visits to the Prison and Police museum, the Courthouse museum and perhaps saddest of all the Workhouse museum and garden giving us a glimpse of the poverty of a bygone age. The Victorian photographs of row upon row of elderly men and women in standard Workhouse uniform eating their meagre bowl of porridge in total silence (as talking was forbidden) were particularly moving. Wandering around Ripon Cathedral brought a welcome change and lifted the spirits. The Cathedral contains the oldest Saxon crypt in Britain founded by St. Wilfred (an influential and controversial figure in the early English church) in 672, who built a later church at Hexham. The present church contains several architectural styles from the late 1100’s but work stopped in 1540 during the upheavals of the Protestant Reformation. To this day there are unfinished pillars and mismatched arches under the central tower. The Cathedral was in a pretty sorry state but for once the townsfolk of Ripon were indebted to the Scots as they petitioned James VI and I on his way south to London in 1603 and the church was re-founded with a Dean and Chapter (governing body). This must have been a welcome change from the usual Scots “incursions” into northern England over the previous several centuries!

The choir stalls were made by a team of local carvers in the late 1400’s. Each stall in the back row has a lifting seat, with an ornately carved ledge on the underside called a misericord (or “mercy seat”), designed for clergy to lean against when standing during long services. The highly imaginative carvings generally depict stories from the Bible or popular folklore and one illustrates 3 pigs playing the bagpipes, perhaps alluding to the general feeling towards the Scots at the time! For over a thousand years the Hornblower has set the watch at 9pm daily at the obelisk within the market square reminding the townsfolk to be vigilant against all strangers and foreigners. No doubt this was originally intended to warn against Viking raiders but could have been equally useful against the Scots too in later years!

Heading home on our fourth day, our final destination was Wallington in Northumberland, now in the care of the National Trust, and what a gem it turned out to be. Despite the sudden cold and snowy weather many of us headed first to the Walled Garden, a former kitchen garden and now full of colourful themed borders. The sight that greeted us was a riot of tulips in all shades of reds, pinks and yellows. Rather than a formal layout, the garden follows the curve and slope of the brook running through it, with rock garden, paths, curved steps of old-worked stone, ponds and pools, dominated by a superb Edwardian Conservatory. At each turn a new “secret” and intimate vista opens up to enchant the visitor. The wider woods form part of the original pleasure grounds that were developed in the mid 1700’s and offer formal views with winding woodland walks and natural planting. Sadly the red squirrels did not come out to play during our visit! One of the further surprises on offer are the four dragons’ heads grinning from the lawn.

The visitor passes under an elegant Palladian Clock Tower into a vast grassy courtyard and from there into the House. The main state rooms contain fine Italian Rococo plasterwork, in complete contrast to the exterior of the house, which is relatively unpretentious. Built in the late 17th century, Wallington has been owned by the Fenwicks, Blacketts and Trevelyans – all making their mark on this huge estate. Undoubtedly the Central Hall is the most unusual room. Originally an open courtyard this space was roofed over in the 1850’s, and in keeping with the Trevelyan’s wish that Wallington should be a centre for intellectual, artistic and scientific pursuits, the courtyard is now reminiscent of an Italian Renaissance palazzo complete with wall paintings to “illuminate the history and worthies of Northumbria”. The ground floor consists of eight tableaux illustrating the history of the region, from the building of Hadrian’s Wall to the industrial achievements of Tyneside, interspersed with flowers and plants all painted with naturalistic precision in oil directly onto the stone. The areas between the arches are embellished with medallion portraits of the eminent in Northumbrian history, from Hadrian to George Stephenson. The upper storey depicts the story of the battle of Otterburn of 1388. An unconventional family, the Trevelyans made the Central Hall the hub of their house. Wallington made a wonderful conclusion to what had been a superb four day spring trip for our members. We returned home weary, but full of happy memories and new discoveries.