Hugh Elder & Son, Grain Merchants & Millers

Queen Anne Street & City Mills, Inglis Street, Dunfermline

by George Beattie

David Elder, born in Dunfermline in 1806, the founder of the above firm, is described as being ‘a man of common stamp’. Apparently cast upon his own resources in early life (Dunfermline Press of 23rd July, 1870) Mr Elder learned the weaving trade, and maintained himself by it, at the same time embracing every opportunity that presented itself for the cultivation of his intellect until, by degrees, he wrought himself into the position of assistant to Mr Haxton, Principle of the High School, and thereafter taught successfully in Pittencrieff Street for 13 years. Poor health cut short his teaching career and, in 1834, whilst King William IV was still on the throne, Mr Elder went into business for himself, firstly as a grocer with a house and shop at the corner of High Street and New Row. Most grocers of the time also dealt in grain and this soon led to him opening a granary on the south side of Queen Anne Street (situated opposite the later premises of John Goodall & Co). The granary was apparently purpose built and is likely to have been the premises later occupied by The City Bakery for many years. David Elder died in 1870, at High Street, Dunfermline, and his son, Hugh, took over the running of the business. The name Hugh Elder & Son was then applied to the firm and it would be known as such for the next 100 or so years. Around this time Messrs Elder were also operating a small flour mill at Oakley.

In 1905, Hugh Elder built an extensive mill and office premises, known as the City Mills, in Inglis Street, together with several huge buildings for grain storage purposes. These premises were located at the north end of Inglis Street, adjacent to the railway goods yard of Dunfermline Upper Station, and had their own railway siding providing the business with ready access to rail transport – see photo above. The Queen Anne Street granary was given up at this time but later became the bakery for Dunfermline City Bakery. In 1906, Hugh Elder’s son, Archibald, joined his father in the business and both men built up a sound business with a wide-ranging supplier and customer base.

LHS C. 1910 photo of an Elder’s horse drawn lorry at the City Mill dressed up for an agricultural show with probably members of the Elder family at the rear. RHS C. 1925 and Elder’s form of transport has moved on to a motor lorry.

The principal product from the new premises was oatmeal, which was a new venture for the company but one which would, over the ensuing years, prove to be very successful. In addition to the milling business however, Elder was a principal supplier to the farming industry throughout east/central Scotland of animal feeding produce, artificial manures and oil cakes. They were also agents for agricultural implements, etc. This involved a significant number of sales staff who travelled throughout the farming areas seeking orders for the firm. Names of travellers that have been mentioned as being with the firm over the years were Jimmy Torrance, Willie Strang, Fred Lees, Jack Hutchison, Charlie Cope, Tom Brough, David Wilson and Eddie Gordon. Most of those mentioned were with the firm for a good number of years with Jimmy Torrance and Charlie Cope, who were directors when the business finished up in 1968, having served from the 1930s.

Outside his business, Hugh Elder had very few interests, although, in his younger days he had been an enthusiastic volunteer. A sad incident involving Hugh and worthy of mention, occurred on the evening of 7th July, 1876, at Hill of Beath Rifle Range. Hugh, then a member the First Fife-shire Rifle Corps was engaged in target practice at the range and asked a good friend, Andrew Rumgay to act as marker for him. Strict regulations were in force on the range to ensure the safety of all parties using the range, including the requirement on marksmen not to fire when the danger signal, a flag, was exhibited. When the danger signal was raised, the marker knew it was safe to check the target. Rumgay agreed to act as marker and took up a position close to the target, some 600 yards from where Hugh was firing. Hugh fired five shots at the target which were signalled as alright. On discharging a sixth shot from his rifle from his rifle loaded with a ball cartridge, Hugh immediately realised something was wrong, and ran to the target, where he found Andrew Rumgay dead, with a wound to his head. Hugh Elder was subsequently charged with culpable homicide and reckless discharge of a firearm, and appeared for trial at Dunfermline Sheriff Court on 29th August, 1876. Two witnesses gave evidence to the effect that the danger signal had been faulty, and in fact had remained stuck in the ‘half up’ position for several days after the incident. As the case was based on Hugh Elder having discharged his weapon when the danger signal was raised, the Crown subsequently withdrew the charges and the Sheriff (Crichton) accordingly directed the jury to pronounce Hugh not guilty. The verdict was greeted with ‘great applause’ in the packed courtroom, and the Court Officer had to quieten the assembled crowd down.

Hugh Elder died in 1933, aged 83 years, having earlier that day spent time at the mill. His family home for many years had been Walmer House (now the office premises of Malcolm, Jack & Mathieson, Solicitors), Walmer Drive, Dunfermline. Archibald Elder (better known by his staff as A.J.) then took control, becoming managing director in 1942 when the firm became a limited liability company. By this time the family had built up a large business, with grain interests extending over the greater part of north-east Scotland.

Flora Cope (m/s Ferrier) – interviewed in 2011 – started work in 1944 as a junior in Elder’s office and worked her way up to company book-keeper by the time she left on her marriage to Charlie Cope in 1963. She said there would be about 12 staff in Elder’s office when she started but, by the time she finished some twenty years later, this number had diminished to 4 or 5. Flora spoke highly of A.J. Elder, describing him as a very popular boss with both the mill and office staff and always ready to help anyone with a problem. Hugh Elder Jnr., however, was much quieter and more remote. A feature article in the Dunfermline and West Fife Journal of 25th May, 1949, re-called the early days of the Inglis Street works and also the situation in 1949:-

“Mr A.J. Elder, representing the third generation of his family in the business continued the policy of expansion, keeping it abreast of modern development and scientific knowledge, with the result that it is now one of the most important firms of its kind in Central Scotland. In the early years of the present century the milling of oatmeal was only a small part of the general business of grain merchants. Then came the 1914 -18 war and imports of food from abroad were severely cut and the demand for home produced oatmeal rocketed to heights previously un-known in the history of the industry. But the boom was short-lived. At the end of hostilities and the return to normal trading conditions the Scottish oatmeal millers found they could not compete with the prices offered by their competitors in Canada, Ireland and the Continent. The market for oatmeal slumped.

However, along came World-War-Two in 1939 with the intensive blockade of Britain’s overseas food ships by the German U-boats and once more the cry went out for home-produced oats. Production was stepped up to record figures and at the City Mills, Dunfermline, the plant worked almost continuously for 144 hours each week turning out meal for human consumption, not only to augment civilian rations, but for use by the British and Allied forces. Butchers and bakers used it and flour millers bought it as a diluent for flour, while it also replaced rice as a dusting material in biscuit factories. Between 1942 and 1945 the City Mills was turning out some 5,000 tons of oats each year for human consumption. After the 1939-45 war history repeated itself. With the abnormally high war-time consumption of oatmeal gone, the demand slumped again. Furthermore, the market is now flooded with prepared breakfast cereal.

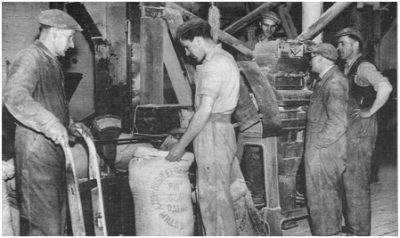

A sack of oatmeal being weighed at the mill by Alec Ogilvie. Others (left to right) are James Pringle, Sam Somerville, Jack Scott and Neil Williamson

The majority of the oats used by Messrs Hugh Elder & Son for milling come from the eastern farming counties of Scotland. Preference is given by the Dunfermline firm to the various types of thin-skinned oats, but difficulty has been experienced in persuading the farmer to grow these, as the yield is greater from other varieties. ‘Past generations of farmers have been inclined to look upon the grain merchant as a necessary evil,’ said a director of the firm, ‘but with more scientific methods of farming and greater opportunities for agricultural education, the agricultural community now realises that the many and varied functions of the grain merchant are a valuable part of the agricultural industry, and can be of enormous benefit to every farmer.’

Seventy workers are employed by the firm at the City Mills and in 1943 the firm was incorporated into a private limited company to enable certain of the employees to take up shares on a profit-sharing basis.Oldest employee is 67 year old head miller Jack Scott, 78 James Street, Dunfermline, who has been with Messrs Hugh Elder & Son for forty years.

Let us follow the actual processes which are necessary before the oats are turned into oatmeal ready for sale in the shops.The sacks of oats are brought direct to the City Mills by road, or in some cases by rail to a special siding alongside the mill building near to Dunfermline Upper Station. The oats are then taken to the top flat of the mill by elevator where they are fed into a hopper before passing through three cleaning machines which remove impurities in readiness for the drying kiln.

Left hand photo taken from the roof of the City Mills looking down the outside hoist by which sacks were unloaded from railway wagons. Jock Young and Sandy Henderson are seen unloading. Right photo shows Willie Appleford and Hugh Brown stack bags of oats on their arrival at the top of the elevator.

The drying of the grain is one of the most essential features of oatmeal milling and it is important that the correct moisture content is left in the oats. This moisture content of 7 per cent maximum is tested three times every twenty-four hours. In addition an automatic temperature recorder produces a chart showing the temperature of the kiln throughout the period. In the old days of milling the drying was done in kilns, the oats being continuously turned by hand to allow the hot air from the furnace below to pass through the grains. Today, however, Messrs Hugh Elder & Son have an automatic drying kiln into which the oats are fed at the top, gradually passing through a series of perforated plates and heated by a draft warm air until they emerge at the bottom ready for milling. The kiln can deal with an average of between 25 and 30 cwt. (1250 to 1500 kg) of oats an hour.

After drying, the oats are passed through a further cleaning process eliminating impurities before they enter the shelling machines where the husks are removed from the grain. It will be noticed that this process of ‘de-husking’ takes place after the kiln drying and is the sequence adopted by the Dunfermline firm in common with other Scottish millers. In England, however, the process is reversed, but the Scottish method appears to be better, for Scotch oatmeal can always be sold against the English product, even at a price difference. Although the husks have been removed the oats are still not ready for grinding. The dust and husks have still to be removed from the bulk, and this is done by sifting and shaking the grain and fanning it with strong currents of air.

A special separator called a ‘Paddy’ machine then takes out any oats which are still unshelled or any other impurities remaining in the groats, as they are called after the removal of the husk. Finally, the groats go to the cutting rollers or to the meal-grinding stones, which grind them into the required grade of oatmeal. When the grinding process has been completed the oatmeal is elevated and dropped down a chute and into a sack where it is drawn off and weighed.”

Archibald Elder remained in control of the firm until his sudden death in March, 1953, aged 66, at his home, Pitbauchlie, Aberdour Road, Dunfermline (now the Pitbauchlie House Hotel). His obituary in the Dunfermline Press of 21st March, 1953, stated that he had been educated at Stanley House School, Bridge of Allan. He was prominently involved with agricultural affairs, being a director of the Royal Highland Agricultural Society and a former president and honorary vice-president and member of the committee of the Western Division of the Fife Agricultural Society. Owner of the well-known Touch herd of large white pigs, he was also a great lover of horses and for a time was a member of the Fife Hunt. Mr Elder was chairman of the Dunfermline Burgh National Liberal and Unionist Association, a position to which he was elected in 1949. When he took over the reins of office, the prestige and influence of the Association were at their lowest ebb. Since then, it had been built up to a strong position, mainly due to Mr Elder’s efforts, and, under his chairmanship two difficult Parliamentary elections were fought in support of the candidature of Mr Stuart J. Kerr, Chalfont St Giles, Buckinghamshire. In 1951, Mr Elder was elected to the committee of the Scottish Conservative Club, Edinburgh. Many years’ association with the Fife and Forfar Yeomanry began in 1907, when he served as a trooper in B Company. Commissioned in 1916, he served in the 1914-18 war with the 16th Highland Light Infantry and the 9th Black Watch in Belgium and France. He was twice wounded. He re-joined the Fife and Forfar Yeomanry when it re-formed as a Territorial Army unit in 1921, and served until 1928 as second-in-command. During the 1939-45 war, he held the rank of Lieutenant Colonel in the Home Guard. A staunch supporter of the Dunfermline branch of the British Legion, an organisation to which he rendered noteworthy service during the early years of its existence, Mr Elder was for many years its joint secretary.

Archibald’s son, Hugh, succeeded his father as managing director, working with fellow directors David Marshall, James Torrance, Charles Cope and Daniel S.C. McNeill. David Marshall was Elder’s company lawyer and a partner in the Dunfermline firm of Stevenson & Marshall, Solicitors; Jim Torrance and Charlie Cope were commercial travellers with Elder, whilst Daniel Stewart Clink McNeill was the company secretary. Daniel McNeill had joined the firm in 1941 when he returned to Scotland from Burma where he had worked with a tea company in Rangoon.

The above photo shows some of Elder’s staff in 1949 with those named by Flora Cope as follows:- back row, Neil Williamson, Sandy Henderson, Flint Harrower and Jimmy Williamson, who was the maintenance engineer. Front row: Andrew Hendry, Margaret Russell, Irene Stenhouse, Margaret Penman, Jack Scott, who was head miller, not known, Flora Cope and Betty Edwards. Those in the middle row could not be identified. City Mills, like most Fife businesses of the time, closed completely for the ‘fair fortnight’ in July each year. Whilst closed during this period the opportunity was taken to seal off all doors and windows of the premises, then pump gas into the building in order to kill off the large number of rodents that had taken up residence during the previous year.

During the late 1950s/early ‘60s, with the advent of ‘ready to serve’ breakfast cereals and the medium of television advertising, oatmeal declined in popularity with the result that the market began to fall year on year. Elder’s work-force also fell from a peak of around 100 during the war years to about 20 by the 1960s. It came as no surprise when the Dunfermline Press of 18th May, 1968, featured an article stating that the Elder firm was going into voluntary liquidation. Mr Elder was quoted thus, “After much discussion and with great regret my co-directors and myself came to the decision some months ago that our old-established firm, which was founded in 1834, would have to go into voluntary liquidation. This was necessary in the interests of the shareholders because, for some time, the return on their capital was inadequate. We also feel that to continue might endanger the value of their shares.”

Mr Elder went on to state that it was his intention to start up a new enterprise, likely to be named Hugh Elder (Dunfermline), Ltd. He explained that the new company would trade directly in purchasing cereals from farmers, and supplying their needs where necessary in feeding stuffs, cereal and grass seed. The business would be conducted from Mr Elder’s home at ‘Tighnult’, Kinnesswood, Kinross. It is thought that this venture did not, in fact, get off the ground and that Mr Elder instead went into the hotel business in the Oban area.

The City Mills building, not being particularly suitable for any other type of industry, was demolished in the 1970’s. The site was later incorporated into the Carnegie Retail Park, with a branch of B&Q occupying the area where City Mills once stood. The only legacy left in the town from Hugh Elder’s days is the block of houses in James Street, built c.1898 to house many of his employees and still known today as Elders Buildings.