W. N. Mitchell & Sons Ltd

Aerated Water Manufacturers

43 Pilmuir Street & 131 Garvockhill, Dunfermline

by George Beattie

William Nicol Mitchell was born in 1883, at Middle Mill Farm, Markinch, the son of a ploughman, Robert Mitchell. On leaving school he entered the employment of Robert Douglas Ltd., Aerated Water Manufacturers, at Lothrie Works, Wemyssfield, in Kirkcaldy.

When Messrs Douglas, in 1911, opened a new factory in Dunfermline, Mr Mitchell was appointed manager there. These premises were located on the east side of Townhill Road, later to be occupied by Dunfermline Railwaymen’s Social Club and Bowling Green, and now a housing development named Leny Place. The Mitchell family residence was then on Townhill Road, about 50 yards from the factory.

The main Douglas factory was still in Kirkcaldy and, as transport at that time was mainly by horse and cart, substantial stabling facilities were required at both sites. One story passed down through the Mitchell family from those times concerned the continuing loss of soda siphon bottles from the Dunfermline depot. One of the delivery drivers was suspected and the matter was solved one day when his horse shook a siphon out of its nose bag.

In 1936, when Mr Mitchell was passed over for the manager’s job at Douglas’s Kirkcaldy headquarters, he decided to cross the Forth to set up in business as a soft drinks manufacturer, at the Itspring Works, in North Berwick. This was where sons William and David would meet their future wives.

While business was brisk in that popular holiday resort in the summer, it tended to be uneconomically slack during the winter months due to the sparsity of the resident population. Within two years, Mr Mitchell decided to transfer himself, his family, and his business back to Dunfermline, to a former smithy at 43 Pilmuir Street. These were the former premises of blacksmiths, Robert Wilson & Son, who had traded there for several decades.

Although this was almost on the eve of World War Two, the move back to Dunfermline was soon fully justified. The first extension to the property came within a year or two, with the acquisition of the handsome grey-stone block of three houses adjoining the smithy, for office and residential purposes. The three houses were subsequently occupied by members of the Mitchell family.

The front entrance to the factory (above) was from Pilmuir Street, a short distance north from Carnegie Street, and the Dunfermline/Stirling railway line formed the north boundary, with Alstons, the wholesale confectioners, on the south side. On the opposite side of Pilmuir Street was Mrs Duncan’s sweet shop. The goods entrance to the factory (below left) was from Carnegie Street, down the right hand side of the Fire Station. Originally the rear of the factory had a row of lock-ups for transport and storage but these were later demolished and a loading and storage area was built (below right). Transport in the early days was all petrol driven and a fuel pump and tank were on site.

Sugar, the base ingredient of soft drinks, was used in granulated form and mixed with cold water until the required density of syrup was acquired. The sugar came in one hundredweight sacks from the sugar beet factory at Cupar. A lorry collected 6 tons every week and this was all hand loaded at Cupar from stacks of sacks up to 50 ft high. A wheeled conveyer belt was rolled into place and the sacks were flung on. The lorry was positioned under the conveyor which dropped the bags onto the driver’s shoulder and he then stacked them on the lorry. There were no forklifts to make life easier.

On arrival at Dunfermline the lorry reversed through the front gate and the bags were carried through a close and stacked three at a time onto a clutch driven hoist which lifted them through the floor to the syrup room where female members of staff swung the load away from the hatch and the operator, with considerable dexterity, released the clutch and dumped the load on the floor. The girls then stacked the sugar and returned for the next load.

The factory was heated by an upright coke boiler which also provided steam for the bottle washing plant. The boiler went through 6 tons of coke a fortnight, obtained from the gas works in Elgin Street. This required driving a lorry under a coke hopper and filling large sacks in a cloud of dust, no masks were thought of in those days. Delivery at the other end consisted of carrying the bags to a coke mound and emptying them out. The driver then crossed Pilmuir Street to the Carnegie Baths to scrub the grime out of his pores.

Leslie Mitchell, grandson of the founder, recalled his earliest memories of the Pilmuir Street premises as ‘the sweet aromas of various fruits and sweet sugar syrup, the smell of the caustic soda from the bottle washer and the smell of coke dust at the open grate of the steam boiler’. Lorries were not fitted with heaters and the windscreens had to be rubbed with anti-freeze to de-ice them. Lorries would break down in the winter when the temperature sank so low that the diesel froze in the fuel tank. Many hours were spent with a blow lamp thawing them out and often a few gallons of paraffin were added to the tank to stop the diesel freezing. Memories included bottles exploding as they froze and rows of multi-coloured icicles hanging under the platform of the lorry. Delivery lorries went out no matter how bad the weather. Every vehicle carried a shovel and getting stuck was not an option. Leslie recalled one winter driving down from Saline with the snow drifts at the side of the road being above the cab of the lorry.

New glass bottles from Alloa Glassworks were delivered in cartons of 30 with the whole workforce ceasing production to form a human chain to empty the lorry and stack the cartons. The bottling process at that time was as follows:- Empty bottles were de-stoppered manually and these were then sniffed to make sure there were no foreign substances, i.e. petrol or disinfectant. If there was any indication of any such substance found these bottles would be destroyed. The tops were then washed in a screw washer and re-used. The bottles were fed into a bottle washer which blasted the inside and outside with hot caustic water then cooled back down with cold water rinses. The clean bottles were placed manually on a conveyor leading to a “syruper”.

From the upstairs syrup room flavoured syrups were gravity fed to the syruper which charged the bottles with 4 fluid ounce of syrup. This then ran into the 24 head bottle filler which filled carbonated water at a rate of 300 dozen an hour. Screw tops were manually placed in the necks and a ‘screw tightener’ tightened the tops automatically then conveyed the bottles to the labeller. After labelling the bottles were held upside down to allow the syrup and carbonated water to mix through and then they were placed in a case and a glued paper top-strap was applied to indicate that the bottle had not been tampered with. This strap also carried the price of the bottle to the public as these were the days of resale price maintenance. This process was modernised with the change from stoppers to metal caps which were automatically applied when a new inline capping machine was installed. Another inline machine to turn the bottles over did away with the need to upend the bottles and an automatic crating machine was also installed.

Making good use of his former contacts in Fife, Mr Mitchell’s business soon proved viable and the company supplied many of the Italian families in the area through their chip shops and ice cream parlours, namely Corrieri, Maloco, Vernolini, Ugolini, Macari, Divito, Ferrari, Tognarelli and Catignani, also the Keddie family who ran a fleet of horse-drawn chip vans, and William Best’s fruit and vegetable vans. The company was also accepted onto the National Coal Board’s list of approved suppliers supplying over 35 colliery canteens in Fife alone. These outlets formed a good backbone for the sustained sales drive for the next 50 years.

During the 1939-45 war the Mitchell business was fortunate in that, along with Woodrow, it was designated for the productions of soft drinks for the local area – all other local soft drink companies were closed for the duration of the war. On the downside, Mr Mitchell’s three sons, who were destined to follow him into the business, were conscripted into war service and he had to run the factory on his own. During the war sugar supplies were rationed and were occasionally supplemented by wooden barrels of syrup from the Caribbean, depending on the state of the convoys crossing the Atlantic.

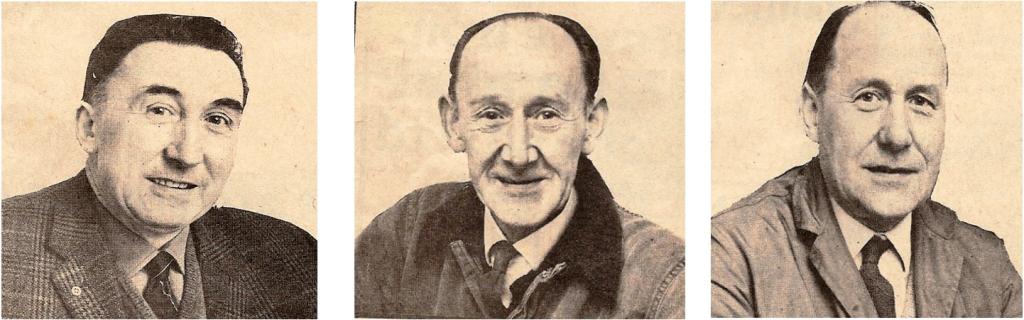

William Mitchell was a past president of the Dunfermline Northern Bowling Club and was also president of Dunfermline Chess Club. He was well known throughout Scotland as a chess player and, over a long period, took part in international games by correspondence. He died in April 1947, by which time he had been joined in the business by his three sons:-

Robert, (above left) who was born in Kirkcaldy, but came to Dunfermline when one year old, on his father becoming manager of Douglas’s new factory. On leaving Dunfermline High School, he served his apprenticeship as an electrician with James Scott & Co, Dunfermline. He left the electrical trade when his father set up business at North Berwick, in 1936. Robert succeeded his father as managing director in 1947.

David, (centre) who was born in Dunfermline, attended Queen Anne School and served his apprenticeship as a motor engineer with Thomson Bros., Rumblingwell. When his father set up in business at North Berwick, David joined him there and, on the firm being formed into a limited company in 1947, he was appointed a director. His main responsibilities with the firm over the years were in connection with the maintenance of the production machinery and servicing of the firm’s fleet of delivery vehicles. One of David’s two sons, Nicol, joined Mitchell’s staff in March, 1970.

William, (right) also born in Dunfermline, went straight into the family business on leaving Dunfermline High School. In World War Two he was a member of the ‘Red Devils’ and was in the first drop in the Airborne Division’s attack at Arnhem on Sunday, 17th September, 1944. He said of that historic event, “It was hot and heavy, and I came out of it alive. Anybody who came out of it alive was fortunate”. He was a prisoner of war from the date of the Arnhem battle until April, 1945. William held the position of company secretary within the Mitchell business and was later joined in the business by his elder son, Leslie.

The ten years following the war were a hard struggle for Mitchell’s business in a climate of austerity but sales steadily grew, culminating, in 1959, in another building extension at Pilmuir Street to increase storage. A depot had been opened at Bathgate to cope with new sales in the West Lothian area but this was soon replaced by larger premises at Birniehill, Bathgate. The West Lothian depot was later moved to Deans Station, near Livingston, and this was supplied three times a week via Kincardine Bridge and Maddiston, before the Forth Road Bridge opened in 1964. The company operated two lorries from Deans Station, supplying customers in Bathgate, Broxburn, Whitburn, Armadale, and anywhere within a 20 mile radius of the base. The opening of the Forth Road Bridge had a marked effect on Mitchell’s sales and led to many opportunities to expand in the Edinburgh area with deliveries direct from the Dunfermline factory. The Deans Station depot was eventually closed about three years after the bridge opened.

Although competition was always keen in this leading area of the soft drinks industry, Mitchell made steady progress, periodically making extensions to their premises until, by the late 1960s, every square foot of their restricted site in Pilmuir Street was in productive use.

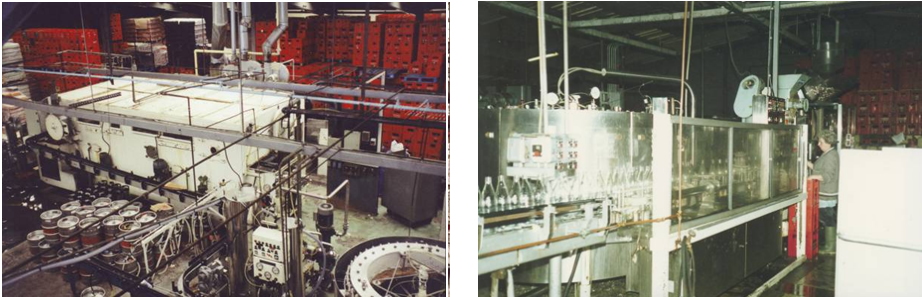

In 1969, it became evident that, if Mitchell’s business was to make further progress, new and larger premises would be required. A site became available at the eastern end of Garvock Hill and there a colourful and spacious purpose-built factory was built, opening in March, 1970. It was the first new factory to be built in Dunfermline by a local firm since the end of the Second World War. The new factory extended to 18,000 sq. ft. of floor space and housed the most modern of manufacturing and bottling equipment. In addition, an office block of some 2,000 sq. ft. was constructed on the south side of the factory.

The new production line was fully automated with a speed of 600 dozen bottles an hour and this led to huge savings in production costs. The larger premises enabled the company to take advantage of bulk purchase at substantially reduced costs. The new factory led to a doubling of production capacity but within two years an 8,000 sq. ft. extension was added to the west side of the building. The lorry fleet was also increased to eight, mostly Bedford T.K. models

In the 1970s the British Soft Drinks Association organised a trip to look at production techniques in the Far East. Members of the Mitchell family took part and visited Singapore, Hong Kong, Thailand and Japan. Of these countries only Japan was more advanced than the U.K., with high automation being the key word. The other countries relied on low wages and were very labour intensive. In 1972, at the International Brewing and Bottling Exhibition at Earls Court, London, Messrs Mitchell were awarded 1st Prize and a Gold Medal for their Sparking Orange Crush, and in 1980 the company was awarded the Diploma of Excellence for their Red Diamond Cola.

Leslie Mitchell recalled some of the problems faced by much of industry during the 1978 ‘winter of discontent’. Mitchell had no union representation at that time but restricted supplies meant limited production at the works. Bus strikes in the area saw Mitchell uplift staff from Oakley, Kelty and Cowdenbeath in the morning and run them home again at night. Liquid sugar deliveries were also disrupted at this time but Mitchell overcame this by shipping in 20 tons of Danish dry sugar. This meant the old sugar mixing machine form the Pilmuir Street factory having to be re-commissioned and the nights were spent turning the dry sugar into liquid form for the next day’s production.

The CO2 strike at the Distillers Company brought the Scottish soft drinks trade to a standstill. Mitchell, however, became aware that a soft drinks company in Greenock, which had closed a year earlier, had a CO2 tank with ½ ton of gas in it. This was bought and a lorry despatched to Greenock to bring it back to Dunfermline. Mitchell’s were immediately ‘back in business’ while competitors were still at a standstill. The same tank was then taken to Belfast, filled there and brought back to Dunfermline in order to continue production. Leslie describes these as ‘heady days when you felt you were flying by the seat of your pants in order to maintain production’.

Mitchell’s sales increased considerably over the next few years until the opening of the first Asda Supermarket on Halbeath Road and the Fine Fayre store in St Leonard Street. With the opening of these stores Mitchell’s sales dropped by 1000 dozen bottles a week. This was a culture shock to the entire soft drinks trade in Scotland as the new supermarket shopping trends forced the industry out of its complacency and led to new innovations in the market to regain lost sales. As Mitchell could not compete with the supermarkets on price, they looked for sales in other areas.

One such diversion was the introduction of ‘Thistle Pops’ which was a lollypop liquid in sachets, made on an Ivers Lee machine, which shops could then freeze as ice lollipops. Also produced was a range of plastic cup drinks with a foil seal cap. These proved very popular and sales exceeded all expectations. In the 1980s post-mix vending systems for pubs and cafes came in where tap water was carbonated and mixed with syrup to provide the finished product. Mitchell’s response was to go the premix route by filling 11 gallon kegs with soft drinks to be dispensed like the brewer’s system. They also produced 20 gallon containers for use in restaurants.

Over the years the size of bottle used in the soft drinks industry changed with the 6 fl oz bottle being replaced by ¼ litre non returnable glass bottles. Sales of the 26 fl. oz. bottles were also receding and these were replaced with 2 litre PVC bottles. This change was successful and Mitchell recovered much of the volume they had lost to the supermarkets. During their last ten years of trading Mitchell, in common with other soft drink manufacturers, was supplying beers and ciders to the licensed trade.

In late 1992, Mitchell’s moved their production to Woodrow’s factory at Pitreavie Business Park. This was followed in April, 1993, by Woodrow taking over the Mitchell business, with the remaining 20 sales, engineering and office staff also moving to Pitreavie. Both firms had been serious competitors in the soft drinks industry for many years in Dunfermline but, as Roy Woodrow said to the press at the time, “We have been in opposition for a long number of years, but we have always got on well and the take-over was very amicable.”

Over the years Messrs Mitchell was fortunate in having a good number of long-serving employees such as Robert Mitchell, no relation, who had been with the firm as a driver/salesman/checker for 50 years when he retired. Likewise, John (Ian) McConnell served for 38 years as a driver/salesman, Nancy Blench for 34 years as a production operator, and Jackie Barrie for 32 years as a driver/salesman. Ian McConnell said it was a good firm to work for. He began at Pilmuir Street as a van boy, aged 15, in 1955, and for many years thereafter delivered to the Lothians area where he managed to secure many new customers over the years.

The passing of Mitchell’s business in 1993 was perhaps a sign of the times with smaller firms struggling against the purchasing power of the ever-increasing supermarkets and the decline of working-men’s clubs in the area. Whatever the cause, it meant that Dunfermline had gone from sustaining five or six soft drinks companies during the middle part of the century to having only one at its latter end.