George Kay & Sons, Coach-builders

by George Beattie

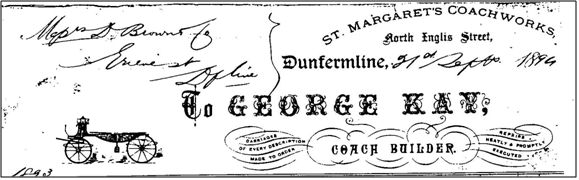

Born in 1854, George Kay served an apprenticeship as a coach-builder with the firm of David Doig who had premises in Randolph Street, Dunfermline. In 1881, he entered into a partnership with William Darroch Wilkinson and founded Messrs Kay and Wilkinson, Coach-builders, operating from a small workshop off New Row, Dunfermline. The Dunfermline Trades Directory of 1885 shows Messrs Kay and Wilkinson, Coach-builders, at 8, 10 and 12 New Row. The 1888/89 directory shows that the firm was operating at St. Margaret’s Coachworks, North Inglis Street. Mr Wilkinson was a Glaswegian and he left the business shortly thereafter to start a coach-building enterprise for himself, named Comely Park Coach Works, at 89 Priory Lane, Dunfermline.

George Kay, however, carried on St Margaret’s Coachworks under his own name and soon gained a reputation as a master craftsman in the art of building and repairing horse-drawn carriages of the Victorian era such as landaus, broughams, dog carts, etc. In 1912, the firm moved again to larger premises at No. 34 Inglis Street where the business was to operate until 1976, when re-development of that area necessitated a further move to more modern premises in Campbell Street. During the early part of the century George Kay was joined in the business by his three sons, Dick, Jimmy and John. Dick and Jimmy served their apprenticeships as coach-painters whilst John was trained to run the office. Dick, who in later years would play a prominent role in running the firm, started work at the age of 11 years and, as he progressed through his apprenticeship, he showed a flair for sign-writing. For many years he was responsible for much of the lettering on the coaches, lorries and vans leaving Kay’s workshop.

Coach-building was in its golden era around the turn of the century and Kay’s enterprise embraced a variety of skilled craftsmen besides coach-builders. There were painters and sign-writers, wheelwrights who made the wooden wheels for the carriages and blacksmiths who fitted the wheels with iron rims and also forged the iron hubs for them. It appears that many of these craftsmen enjoyed the occasional tipple whilst they worked and it was not unknown for the young Dick Kay to be sent across to the Railway Tavern (then on the corner of Inglis Street and Reform Street) with a piece of sandpaper on which the journeymen had written their beer and whisky order for the day. The drinks bill was apparently always settled on pay day. Inglis Street around that time appears to have been an interesting and busy place each morning with traders known as ‘cadgers’ with light carts or hand-barrows on their way to the Upper Railway Station to collect their supply of fish from the fish trains before setting off to sell their wares around the town and countryside.

Many of these fish carts were made at Kay’s workshop. The early part of the century also saw the steady introduction of the horseless-carriage i.e. the motor car. George Kay apparently resisted the temptation to have anything to do with these new-fangled contraptions claiming they would ‘just be a flash in the pan’. He was so convinced of this that he turned down the opportunity to be the local agent for Wolseley cars, a franchise which would eventually go to his good friend and neighbour, John Goodall. Despite these reservations however, George Kay had, in 1897, collaborated with the Dunfermline engineering firm of Michael Tod & Co., in the building of a prototype motor car known as the Tod Three-wheeler. Kay undertook to make the body-work for this vehicle which sadly, did not get beyond the prototype stage.

A horse-drawn trap built by George Kay in 1900, also for the Dick family of Transy, but photographed in 1950

C. 1910 – This Shetland pony trap was built by George Kay for William Dick of Transylaw and, in tandem with the pony, Silverton of Transy, twice won Champion of Show at the Royal Highland Show and was also twice Champion at the Royal Show of England, the pony and trap being judged as a unit.

Throughout the first two decades of the century George Kay’s business thrived as he built and repaired the many horse-drawn carriages and vans used by the local professionals and tradesmen of the day such as doctors, lawyers, butchers, bakers, grocers, fish merchants, milkmen, carriers and builders. However, Kay’s workshop ledgers of the early 1920s show that by that time the firm had accepted the horseless-carriage, as by then many motor vehicles of the day were being repaired by Kay. This was a natural progression as all early motor vehicles had coach-built bodies and required the skills of Kay’s staff to repair any damage to them. These ledgers indeed read like a ‘who’s who’ of West Fife at that time with customers such as :- Erskine Beveridge of St. Leonard’s Hill House; Doctor Robertson of East Port Street; Mrs Lafitte of Hartley House, Viewfield Terrace; Mr. Thomas McLean of Aberdour Hotel; Thomas Blair, Solicitor, East Port; William Dick of Transylaw; John Scott, Butcher of High Street; etc., etc.

The journals also illustrate the wide variety of motor vehicles on the streets of Dunfermline at that time, many of which were of British make but are now only names from the past. The ledgers also indicate how in that era every effort was made to repair a defective part as opposed to the situation today where a replacement part is nearly always fitted, perhaps illustrating the difference between the craftsmen of that era and the fitters of today. It must be acknowledged that labour cost was relatively inexpensive in those days and this factor probably contributed to this state of affairs. Notwithstanding, this was undoubtedly an era where craftsmen took a pride in their work and made every effort to achieve high standards.

Dick Kay typified this way of thinking in his approach to coach-painting. As most such work of that time was finished off by a coat of varnish it was very important that this final coat did not become contaminated by specks of dust or clothing fibres which might mar the quality of the finished article. In order to achieve the perfect finish Dick is reputed to have regularly worked either during the night or on a Sunday morning when no one else was in the workshop to stir up dust. As an added precaution he would spray the paint-shop floor with water to ‘lay the dust’ and as a finale he would strip off his clothes to reduce the risk of clothing fibres and would then proceed to apply the varnish in the nude.

C. 1920 – Now at 34 Inglis Street with an elderly George Kay (centre) and sons Dick (right) and Jimmy (second from right)

Dick Kay had fought in the first world war having been called up for active service in 1915, at 38 years of age. He served initially with the Black Watch before transferring to the Royal Scots with whom he saw action in France. In an interview with the Dunfermline Press in January, 1967, to celebrate his ninetieth birthday, he recalled the horrendous conditions he, and many thousands of other troops, encountered in the trenches there, resulting in him becoming seriously ill with trench fever. As a consequence he was repatriated to England where he slowly regained his health and finished the war as a member of the Royal Ordnance Corps. A tape recording of part of the above interview is held by the Local History Department of Dunfermline Library.

In 1922, Dick was taken into partnership in his father’s business with a view to him eventually taking over, on George Kay’s retiral. In 1929, Kay became the first firm in Fife, if not in Scotland, to make the move from brush-painting to spray-painting of vehicles. This necessitated Kay’s painters learning new skills relating to a totally different process from that which had prevailed for many years. Around 1937, by which time George Kay had retired, all appears not to have been well with the management of the company as at that time Dick Kay’s son, also George, who had served his time as an apprentice motor engineer with the Fife Motor Company, before going on to become workshop foreman with John Goodall & Co., was enticed to make the short journey across Inglis Street from Goodall’s Garage and take charge of Kay’s operation. In 1941, George Kay, the founder of the firm, died suddenly at his home, ‘Daw-Kay’, 117 Pilmuir Street, Dunfermline. He was 87 years of age and had had twelve of a family, only six of whom were surviving at the time of his death.

John Johnston, who began his coach-painting apprenticeship with Kay in 1938 after having been a delivery boy with James Ritchie, the Fishmonger, for a year, recalled his colleagues of that time indicating that the introduction of George Kay had given the company a new sense of direction. All that was about to change however with the outbreak of war in 1939 and, like many other businesses, Kay lost a number of the younger members of staff to the war effort. John Johnston was one of those called-up and from 1940-45 saw action in the middle-east where, for some strange reason he was engaged as a cook. Returning to work for Kay on demob in 1946, John saw the business start to pick up again under George Kay’s management and move almost totally into the repair of accident damaged motor vehicles. John spoke of the changes to working practices during his time with Kay. He recalled that one of his first jobs was on a white MG, brought in by the owner for a complete paint job. It took John almost a week to prepare the vehicle for paint and the same again before it could be returned to the owner. A car re-spray then meant the car being totally stripped of paintwork, cleaned and varnished with pure cellulose before receiving several coats of undercoat then colour, each coat being flattened with wet and dry sandpaper. The final polish with the wax left the vehicle so shiny that “you could see your face in it”.

John, who went on to become foreman painter with Kay and remained with the firm until 1983, when he was forced to retire due to ill-health, recalled some of the lighter moments such as the odd occasion when a cattle beast would escape from the adjacent cattle market in Inglis Street and run amok in Kay’s workshop. He also recalled that just after the war, Dick Kay would march up and down the workshop floor playing the bag-pipes, not always in tune, and certainly not always appreciated by the workforce. Around that time Kay’s workshop was also the venue for a daily morning meeting of Jimmy Kay, Davie Goodall, Archie McCulloch (also of Goodall’s Garage) and John Scott the Butcher, who would for an hour or so set the wrongs of the world (or maybe it was just Dunfermline) to right and then go their separate ways.

Dick Kay, who was still carrying out sign-writing work in his 80s, retained an interest in the firm after his retirement and until into his 90s would make the daily walk from his home at 25 John Street, up the New Row, just to keep an eye on things at Inglis Street. A pipe-smoker from an early age, Dick, nevertheless, was able to negotiate the steep incline of the New Row each day without breaking breath. In 1968, in his 92nd year, he passed away at his home.

In 1949, Norman Harris, a nephew of George Kay entered the firm on leaving school and was destined to take over the company on his uncle’s retiral some years later. This saw the start of an era which would see the introduction of hydraulic power tools to straighten car bodywork and heated spray-booths to speed up the turn-over of the paintwork side of the business, a far cry from the early days when it could take two to three weeks to prepare and hand-paint a motor car.

In 1975, as a result of town centre development which would see the new Kingsgate Centre, the Multi-Storey Car Park and the new Bus Station take shape, Kay’s business was forced to make its final move to Campbell Street and into the former premises of the joinery firm of Brown and Templeman (now, in 2010, occupied by Ceramic Tile Warehouse). By that time Norman Harris was running the company, although George Kay retained an interest and, like his father before him, visited the workshop on a daily basis.

In April, 1981, George Kay, the third generation of his family to run the firm, died in Milesmark Hospital, in his 84th year, some six months before the company would celebrate its centenary. Well known in Dunfermline business circles, George was a keen fisherman and also grew his own tobacco. During the Second World War he served as an officer with the Air Training Corps. Something of a workaholic, George Kay, during his almost 40 years in charge of the company, would start work at 6 a.m. each day, finish at 5 p.m. with the rest of the staff and would then return to do the office work each evening between 6 and 8 p.m. In December, 1996, with Norman Harris approaching retirement age and with no family members wishing to carry on the company, the doors of George Kay & Sons closed for the last time when the firm ceased trading.