Shopping for Food and Drink In Victorian Dunfermline

By Sue Mowat

How different, how very different, was shopping in Dunfermline a century and a half ago! In 1861 there were more than 70 shops in the High Street alone – grocers, greengrocers, bakers, tobacconists, booksellers, pawnbrokers, drapers, shoemakers, clockmakers, ironmongers, confectioners, chemists, china merchants and toy dealers. Bridge Street was largely given over to drapery shops and shoemakers and there were more shops in Chalmers Street, Bruce Street, Cross Wynd, Gibb Street, Chapel Street, Guildhall Street, Kirkgate and Queen Anne Street. Everything the household could need or the heart could desire was for sale within a few minutes’ walk.

How different, how very different, was shopping in Dunfermline a century and a half ago! In 1861 there were more than 70 shops in the High Street alone – grocers, greengrocers, bakers, tobacconists, booksellers, pawnbrokers, drapers, shoemakers, clockmakers, ironmongers, confectioners, chemists, china merchants and toy dealers. Bridge Street was largely given over to drapery shops and shoemakers and there were more shops in Chalmers Street, Bruce Street, Cross Wynd, Gibb Street, Chapel Street, Guildhall Street, Kirkgate and Queen Anne Street. Everything the household could need or the heart could desire was for sale within a few minutes’ walk.

This article will concentrate on shopping in the 1860s, mainly because there is a lot of easily-available information about that decade, but also because there had recently been a considerable expansion in the local retail trade. Country-dwellers were no longer restricted to shopping on market and fair days. The Stirling and Dunfermline Railway, built in the 1850s, provided daily access to the town from the west, and an extension to Thornton and beyond brought passengers from the east. The railway station (on the site of the B&Q retail park) was just a stone’s throw from the town centre. Shoppers from the Limekilns and Charlestown district could ride the Elgin Railway train to its terminus in the Netherton, a few minutes walk from the shops.

Village shops would have sold a limited range of basic food and beverages but for a wider selection a trip to Dunfermline was still necessary. Local people frequently visited the various provisions shops because fresh produce like fish, meat, butter, milk, fruit and vegetables deteriorated rapidly when there were no fridges, especially in summer. Older people today will remember the taste of rancid butter and the white specks floating on the surface of tea made with milk that was just ‘going off’.

Grocers

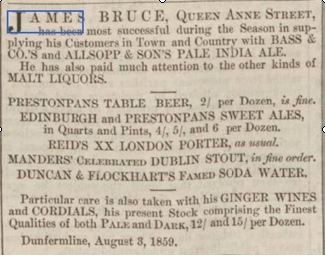

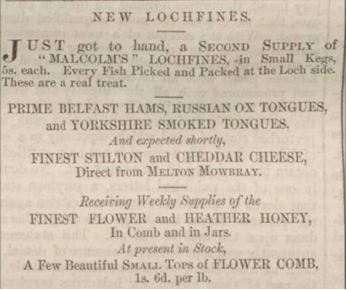

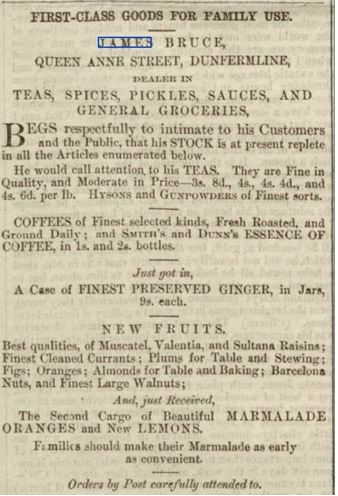

Many of the 13 town centre grocers advertised regularly in the Dunfermline Press and its sister paper the Dunfermline Saturday Press, but the most prolific advertiser of them all was James Bruce, at 28 Queen Anne Street, founder of the firm of Bruce and Glen which some people may remember in its later premises in Bridge Street. Occasionally his advertisement, like the one below, was for general goods, but usually they were more specific, like this one for Lochfyne kippers, ham, tongue, cheese and honey.

Many of the 13 town centre grocers advertised regularly in the Dunfermline Press and its sister paper the Dunfermline Saturday Press, but the most prolific advertiser of them all was James Bruce, at 28 Queen Anne Street, founder of the firm of Bruce and Glen which some people may remember in its later premises in Bridge Street. Occasionally his advertisement, like the one below, was for general goods, but usually they were more specific, like this one for Lochfyne kippers, ham, tongue, cheese and honey.

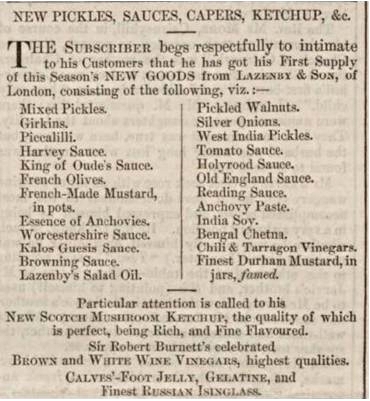

Or the one below, for more than two dozen pickles and sauces. Many of them are familiar to us today, although the soy sauce is advertised as ‘Indian’ but what were Holyrood Sauce, Old England Sauce and Reading Sauce, for instance? And what a pity we now can’t buy the ‘Rich and Fine Flavoured’ New Scotch Mushroom Ketchup or King of Oude’s sauce.

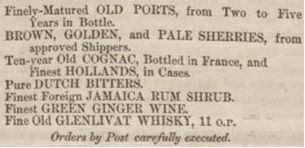

Like many grocers James Bruce also sold wines, ales and spirits.

As the nights drew in he called the attention of his customers to his stock of candles, both moulded and dipped, for the house and ‘moons’ for carriage lanterns. Nervous children were catered for with night lights. By the 1860s gas had long been used for lighting in Dunfermline but mainly for street lamps, loom shops and some shop windows; most households still relied on candle light. Bruce also sold ‘A complete assortment of the Finest LONDON WAX and SPERMACETI CANDLES, PRICE’S and THOMSON’S COMPOSITES’.‘Composite’ candles were made from a mixture of refined tallow and coconut oil. They were much cheaper than wax candles and did not smell and gutter like tallow, so they brought the former luxury of bright, clean lighting within the reach of all but the very poor.

James Bruce and the other town centre grocers operated at the upper end of the market but many people would have been reliant on the smaller establishments to be found in most of the streets outwith the town centre – the Victorian equivalent of the convenience store. In the 1850s there were about 70 grocers in Dunfermline and three quarters of them were situated in streets other than the High Street.

A few people combined grocery with other occupations. Alexander Taylor in the Kirkgate also took up photography and was so successful that he was able eventually to make his living from it. At the other end of the scale, Mary Thomson in Rumblingwell was on the official pauper roll and her two middle-aged sisters worked at the pithead. In the 1851 census 17 women were recorded as grocers, some carrying on the business of a late husband, some having got together enough money to acquire a small stock and eking out a living on the proceeds. For some men the chance to run a small shop was a route out of the poverty of the dwindling hand-loom weaving trade.

This advertisement for the sale of David Short’s shop fittings and stock appeared in the Dunfermline Press of 23 January 1862

Inevitably some failed, like David Short in Pittencrieff Street who became bankrupt late in 1861. This tragedy was compounded by the death earlier in the year of his son Edward, aged 13 months. By the end of the year his un-payable debts amounted to £160 and on 16 January 1862 he called a meeting of his creditors, the main one being John Carmichael (later of Fraser & Carmichael) to whom he owed £40. David had already sent away his wife and surviving child and all his furniture, probably to Edinburgh where his brother lived and where his next two children were born.

David Short was a young man who had only been in business for a few years. John Young of Reid St was an established grocer when he died in 1852 at the age of 54. The inventory of his shop furniture and stock is detailed and the stock in particular reflects the kind of diet that his customers favoured. It is a rather different selection compared with the articles in David Short’s shop but in both cases the list reflects the stock at the time the inventory was taken, which was not necessarily the full range of goods that would have been on sale over a period of time.

Shop Furniture & utensils

A set of liquid measures 6 crystal show glasses 6 tumblers

3 doz ale bottles 3 show barrels 4 tin scoops

Large ham knife 5 small whisky barrels 2 fillers

3 small baskets 2 crystal bottles 2 wooden measures

Stock in Shop

30 gal whisky @ 6s 4 bottles whisky @ 2s 12 bottles twopenny porter 1/6d

10 bottles table beer 1s

c 1 boll oatmeal 12s 56 lb barley 5s 20 lb Dunlop cheese 5/6d

34 lb sugar @ 6d 15 lb tea @ 3/2d 1 lb coffee 1/2d

½ barrel ashes 6d 20 lb starch @ 1/6d 3 doz small bottles caster oil 18s

The Petty Customs

One issue that greatly annoyed the grocers was the centuries-old imposition of petty customs dues on goods brought into the town. Originally the petty customs had been collected from outsiders who brought goods to the weekly markets and while this personal trade continued the system worked well enough. However, in the nineteenth century, with the introduction of railways and decent roads and the growth of international trade, it began to falter. The local customer (collector of the customs) could not exact the dues from the wholesaler, who in some cases lived as far away as the USA, so it fell to the retailers to pay the custom and try to get reimbursement from their suppliers, which in most cases was impossible. This hit the grocers hard because many food and drink items, which now came from distant suppliers, were still subject to paying petty customs.

Late in 1859 the grocers finally rebelled, with strong complaints and petitions to the Town Council. Some of them tried a civil disobedience protest, refusing to pay custom on goods that had been brought to the town from their suppliers but this proved futile because the customer then simply exercised his age-old right to impound the goods until the custom was paid. Eventually the Town Council, some of whom actually agreed that the system was obsolete, revised the table of customs, removing some items and reducing the dues on others. This action mollified the grocers and others who had been affected by the old system and there were no further protests. However the petty customs were not finally abolished until 1880, by which time the £50 a year which they added to the town’s funds was no longer a significant sum.

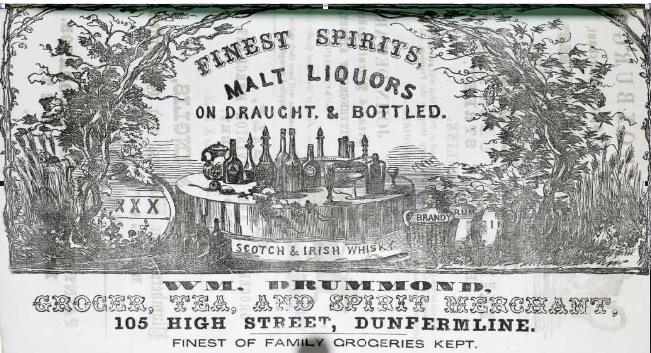

We leave the Grocers with this magnificent advertisement, from the 1866 Dunfermline Almanac.

Fruit and Veg

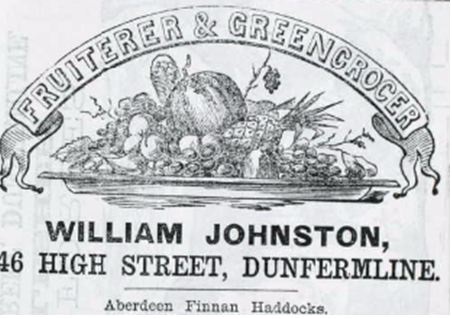

William Johnston’s advert in the Dunfermline Almanac for 1864 neatly sums up two important aspects of the greengrocer’s trade. In the first place, the sale of fruit was the more lucrative part of the business and most greengrocers also sold smoked and salt fish. There were not so many greengrocers as grocers – just thirteen were listed in the 1861 Dunfermline Directory, and all of them were located in the town centre – High Street, Kirkgate and Chalmers Street – there were none in the outlying areas.

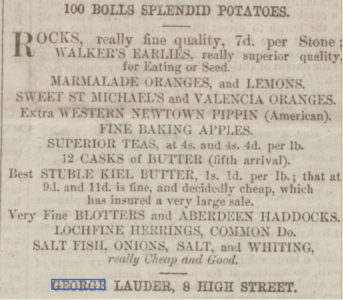

The undoubted doyennes of the trade were both relatives of Andrew Carnegie; his uncle George Lauder had his shop at number 8 High Street and his cousin Thomas Morrison at number 21. George Lauder was in business as early as 1838. When the Dunfermline Press appeared on the scene in April 1859 he tested the advertising water with some modest announcements about his stock – his first advert listed oranges, apples, agricultural salt, cheap (salted) herrings, Lochfyne herrings, Finnan Haddocks, splendid potatoes, whiting and brilliant blacking. George Lauder obviously found that advertising increased his sales so his adverts became larger and more expensive. Here is one from February 1861 – note that some of his apples were imported from the USA. The ‘very fine BLOTTERS’ mentioned in this and several other adverts were actually bloaters – the misspelling was eventually corrected. The only vegetables mentioned are potatoes (Rocks and Walker’s Earlies) for 7d a stone (about 6 kilos) and onions. The marmalade oranges were presumably Sevilles, which are in season in January and February, the traditional marmalade-making months.

The undoubted doyennes of the trade were both relatives of Andrew Carnegie; his uncle George Lauder had his shop at number 8 High Street and his cousin Thomas Morrison at number 21. George Lauder was in business as early as 1838. When the Dunfermline Press appeared on the scene in April 1859 he tested the advertising water with some modest announcements about his stock – his first advert listed oranges, apples, agricultural salt, cheap (salted) herrings, Lochfyne herrings, Finnan Haddocks, splendid potatoes, whiting and brilliant blacking. George Lauder obviously found that advertising increased his sales so his adverts became larger and more expensive. Here is one from February 1861 – note that some of his apples were imported from the USA. The ‘very fine BLOTTERS’ mentioned in this and several other adverts were actually bloaters – the misspelling was eventually corrected. The only vegetables mentioned are potatoes (Rocks and Walker’s Earlies) for 7d a stone (about 6 kilos) and onions. The marmalade oranges were presumably Sevilles, which are in season in January and February, the traditional marmalade-making months.

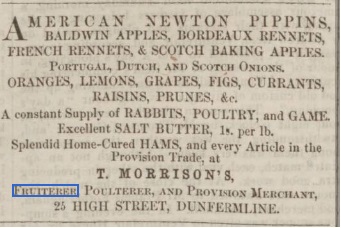

Thomas Morrison started business in the Kirkgate in 1852 but by 1860 he had moved to the High Street and was selling poultry along with his fruit and vegetables. In October of that year he applied to the JP Court for a game licence. James Hunt of Pittencrieff, who was one of the sitting JPs, demonstrated his well-known antipathy to members of the Morrison family by raising a petty objection to Thomas’s application but he was over-ruled by his four fellow JPs and Thomas got his licence.

Thomas Morrison started business in the Kirkgate in 1852 but by 1860 he had moved to the High Street and was selling poultry along with his fruit and vegetables. In October of that year he applied to the JP Court for a game licence. James Hunt of Pittencrieff, who was one of the sitting JPs, demonstrated his well-known antipathy to members of the Morrison family by raising a petty objection to Thomas’s application but he was over-ruled by his four fellow JPs and Thomas got his licence.

Thomas’s December advert in the Dunfermline Press mentions that he now sells rabbits and other game.

Ham is included in the advert and was also sold by George Lauder and other greengrocers. Onions are again the only vegetable mentioned, but there are three varieties.

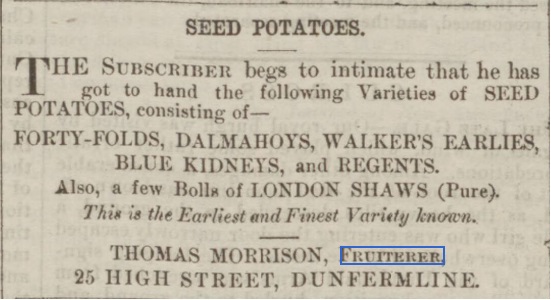

Potatoes were such a staple that they were probably not worth including. March, however, was the potato-planting season and Thomas was ready with supplies of six different varieties. The Fortyfold variety was introduced in 1800 and can still be bought from ‘heritage potato’ suppliers.

Potatoes were such a staple that they were probably not worth including. March, however, was the potato-planting season and Thomas was ready with supplies of six different varieties. The Fortyfold variety was introduced in 1800 and can still be bought from ‘heritage potato’ suppliers.

As its name suggests it is very prolific. Although its skin is purple the flesh is white and it is a parent of the more modern variety, Kerr’s Pink. As time went on Thomas concentrated more and more on the potato trade and when he died at his house in Buchanan Street in October 1896 it had for some years been his sole business interest.

Local Produce

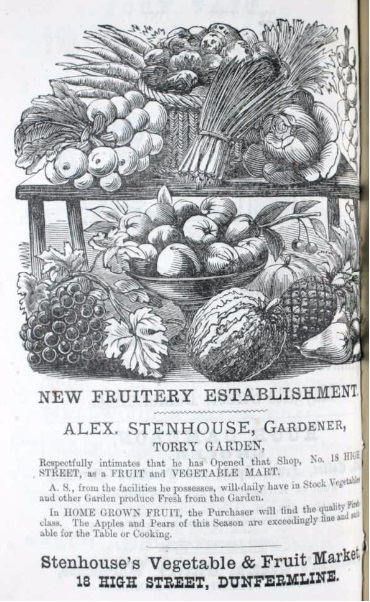

The only vegetables mentioned in adverts by George Lauder and Thomas Morrison are potatoes, onions and carrots and it is clear that these were a minor element in the trade of major greengrocers, but there were a couple of smaller establishments that specialised in locally grown vegetables. Alexander Stenhouse was a Haddington man, who in 1861 was head gardener at Pitfirrane and a frequent prize-winner at local horticultural shows. Meanwhile Isabella Munro, the widow of Neil Munro, was carrying on her late husband’s business at the 7-acre market garden in the grounds of Torry House. Isabella died in 1862 and for a while her son Neil continued to run the ‘Torry Garden’ but in 1865 he sold up and shortly afterwards emigrated to Canada. Alexander Stenhouse bought the garden and in November 1866, in the Dundee Courier, he announced the opening of a shop in Dunfermline. In the following February and March Alexander informed the public that he ‘has got to hand a large stock of GARDEN and FLOWER SEEDS which he intends to Sell at very moderate Prices. Also a good stock of CABBAGE PLANTS of all Sorts CAULIFLOWER PLANTS and Large-Flowered GERMAN STOCKS SEED.’

The only vegetables mentioned in adverts by George Lauder and Thomas Morrison are potatoes, onions and carrots and it is clear that these were a minor element in the trade of major greengrocers, but there were a couple of smaller establishments that specialised in locally grown vegetables. Alexander Stenhouse was a Haddington man, who in 1861 was head gardener at Pitfirrane and a frequent prize-winner at local horticultural shows. Meanwhile Isabella Munro, the widow of Neil Munro, was carrying on her late husband’s business at the 7-acre market garden in the grounds of Torry House. Isabella died in 1862 and for a while her son Neil continued to run the ‘Torry Garden’ but in 1865 he sold up and shortly afterwards emigrated to Canada. Alexander Stenhouse bought the garden and in November 1866, in the Dundee Courier, he announced the opening of a shop in Dunfermline. In the following February and March Alexander informed the public that he ‘has got to hand a large stock of GARDEN and FLOWER SEEDS which he intends to Sell at very moderate Prices. Also a good stock of CABBAGE PLANTS of all Sorts CAULIFLOWER PLANTS and Large-Flowered GERMAN STOCKS SEED.’

Stenhouse’s elaborate advertisement in the Dunfermline Almanac for 1866 shows a mouth-watering selection of fruit and vegetables – grapes, peaches, melons, cherries as well as the more prosaic potatoes, carrots, onions and cabbage.

The 1871 Census reveals that Alexander’s daughter Alison ran the Dunfermline shop and that two of his daughters and one of his sons worked in the garden (two other children were still at school). All seems to have been going well but in 1876 Alexander died of peritonitis at the age of 59. His widow and two of her daughters moved to Dunfermline and carried on a fruiterer’s business for a few years, but they seem to have given it up by 1886.

The other seller of local produce was Robert Anderson, a weaver, who owned and worked in a small loom shop in Pittencrieff Street. Round the corner in Chalmers Street he leased a shop where his daughter sold fresh fruit and vegetables from the Torry Gardens. In July 1864 his first advert appeared in the Dunfermline Press and although he continued for many years to run his weaving business and in the 1891 Census he is described as a greengrocer.

Butchers and a Fishmonger

The Dunfermline directories for 1861 and 1867 list ten fleshers (butchers), most of them in the town centre with one outlier (William Davidson) in Gibb Street. All their meat was locally produced and slaughtered. Fleshers visited farms, markets and fairs to select their stock, drove them back to the town and kept them at grass or in byres until they were ready to kill. Their chief criteria in choosing cattle, sheep and pigs were size and fatness, but they would also assess whether an animal was carrying plenty of muscle in the parts of its body that would produce the best cuts.

Fleshing was a masculine trade, but there was one female butcher in the town, Primrose Addison, the widow of the flesher William Addison. He had died of cholera in 1851, leaving her with a baby and five other young children to support. It is unlikely that Primrose was a completely ‘hands on’ butcher, although she may have helped select animals at market. It might have been supposed that her eldest son, John, who was 15 when his father died would have carried on the business when he came of age, but he became a journalist and moved to England where he founded the Brierly Hill Advertiser local paper and was made an alderman. The second son, James, went into banking and it fell to his younger brother Thomas, who was only aged two when his father died, finally to take over the business in about 1870. The firm of Thomas Addison, butcher, continued in Dunfermline until at least 1941. (William and Primrose’s gravestone in Dunfermline Abbey graveyard is in the form of a distinctive granite Celtic cross on a plinth, which Thomas Addison employed the prestigious firm of Stewart McGlashen and Son of Edinburgh to sculpt in 1891.)

Alexander Dodds advert in the 1866 Almanac underlines the obsession with fatness in an animal. What juicy joints of pork those porkers must have provided! Alexander started business in 1851 and continued until about 1896, when his name disappears from the Dunfermline Directories. His son Robert, brought up to evaluate livestock, took the logical step of starting up as an auctioneer in 1863. Initially he operated monthly on a Tuesday on ‘Premises adjoining Mrs GOODALL’S HOTEL East Port Street’, while also running a more conventional sale room in the Maygate. In 1865 he began auctioning livestock fortnightly, adding the sale ground adjoining the Cattle Market near the railway station to his location in East Port. A report on Dodd’s sale in the Dunfermline Saturday Press of 10 June 1865 gives the prices of bullocks ranging from £16 5s to £19 15s each, fat lambs from 27/6d to 31/6d each and fat pigs £1 19s to £3 17/6d.

Alexander Dodds advert in the 1866 Almanac underlines the obsession with fatness in an animal. What juicy joints of pork those porkers must have provided! Alexander started business in 1851 and continued until about 1896, when his name disappears from the Dunfermline Directories. His son Robert, brought up to evaluate livestock, took the logical step of starting up as an auctioneer in 1863. Initially he operated monthly on a Tuesday on ‘Premises adjoining Mrs GOODALL’S HOTEL East Port Street’, while also running a more conventional sale room in the Maygate. In 1865 he began auctioning livestock fortnightly, adding the sale ground adjoining the Cattle Market near the railway station to his location in East Port. A report on Dodd’s sale in the Dunfermline Saturday Press of 10 June 1865 gives the prices of bullocks ranging from £16 5s to £19 15s each, fat lambs from 27/6d to 31/6d each and fat pigs £1 19s to £3 17/6d.

Butchers did not often advertise in the newspapers so there is little information about the price of their meat but the following prices per pound appeared in press adverts in the 1860s,

Steak 8d – 11d Boiling beef 6d – 8d Best beef 8d Leg of mutton 6d Forequarter (shoulder & chops) of Lamb 5d – 7d Hind quarter (leg) of Lamb 6d – 7½ d

The Poorhouse was supplied with the very cheapest cuts, which would presumably also have been sold in the butchers’ shops. Hough (shin) and neck (clod and sticking) at 2/7d – 2/11d a stone (2½d – 3d per lb) and ox heads at 1/8d a stone (about 1½d per lb).

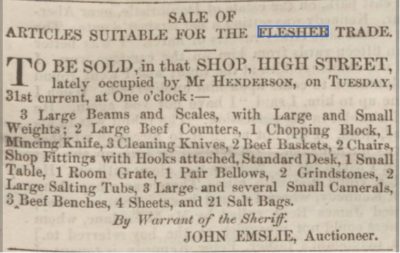

As often happens, it is misfortune that supplies the best information. In 1859 William Henderson, whose shop was at number 50 High Street (nearly opposite the top of Music Hall Lane), was declared bankrupt, and an advertisement in the Dunfermline Press of 26 May 1859 gives a list of the equipment in his shop that was being rouped in a warrant sale.

The Slaughterhouse

Individual fleshers killed their own meat and most of them used the public slaughterhouse, which stood on what is now a vacant space next to the old Velocity nightclub on the corner of Carnegie Drive and Pilmuir St. When it was built in 1787 it was an improvement on the old Fleshmarket in the High Street but by the 1830s the area had become built up with housing and business premises and in 1834 the Town Council received its first complaint about the slaughterhouse. In 1838, in response to a petition by the local inhabitants, the Council resolved to replace it with a new one on a better site but in the end nothing was done. The same thing happened ten years later in 1848 and after that all went quiet until the 1860s, when the wheels once again began to turn.

The earlier attempts to re-site the slaughterhouse had foundered largely on the understandable objections of persons living near the proposed sites, but finance had also played its part. In the 1830s the town was bankrupt and a Trust was set up to get its funds in order. By the 1860s the Trust had done its work and there was now an annual surplus in the municipal kitty. The local press also played its part in agitating for change. When the Dunfermline Press began publication in 1859 it started campaigning for the cleaning up of the various sources of filth in the town, including the slaughterhouse.

On 5 September 1863 the Press contained a full account of what Mr James Morris had had to say at the recent meeting of the Town Council, of which the following is an excerpt:

Not only was the place now a nuisance (ie filthy) in a sanitary point of view but it had become a grievance on the score of the cattle moaning and crying in their confinement and disturbing the inhabitants of the locality….It was opposed to the carrying out of the sanitary laws and besides it was quite a nursing place for vermin….The walls and the floors were holed by rats, who had overrun the place. The rats mounted the rafters and came down the ropes by which the carcases were hung and of course they had free liberty during the night to do whatever they wore inclined…One of their own number who resided near the place had had his whole premises overrun by rats coming from the house and he could only get partially cleared of them after great trouble and expense.

It was not only a nuisance but it was altogether unsuitable for the purpose of a slaughterhouse. It wanted the modern accommodations which were now regarded as needful for the cleanly slaughtering of the animals and of keeping the place clear of offal and other things which ought to be removed to another place…If in the financial condition of the burgh thirty years ago they could look the building of such a place in the face, it was not, surely, too presumptuous to attempt it now, when their financial condition was so much better.

The Council responded in time-honoured fashion by setting up a committee to look into the matter. (One member of the committee was Robert Fisher, whose grocer’s shop was practically next door to the slaughterhouse and was probably the Councillor whose premises had been overrun by the rats.) The Council committee decided that the responsibility for replacing the slaughterhouse lay with the burgh Commissioners of Police, who in their turn set up a committee, but on this occasion the process did not stall. Progress was slow and sporadic but the momentum did continue and in 1869 a new slaughterhouse was finally built, on a site well outside the town at Baldridgeburn, on the west side of the street now called Miller Road.

The Fishmonger

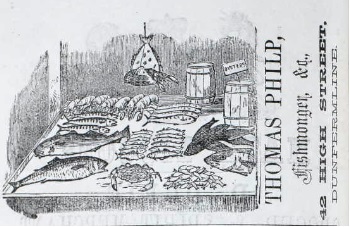

The only seller of fresh fish in Dunfermline in the 1860s was Thomas Philp. He was another tradesman who did not advertise much in the newspapers but he placed an advertisement in the Dunfermline Almanac for 1865 and another in 1866. In November 1861, an Anstruther baker named George Butters set up a fish shop at number 14 High Street. He moved to number 55 in May 1862 but the business did not prosper and he returned to Anstruther and continued in the bakery business. Thomas Philp was a Kennoway man who had tried a couple of trades before becoming a fishmonger. The 1851 census records him as an ironstone miner lodging with another miner and his family in Oakley. By 1861 he was a policeman in Kinghorn, having married Agnes Stein, the daughter of another ironstone miner, in about 1854.

Philp set up his fishmonger’s shop at number 42 High Street in May 1862, advertising that he received a delivery of fresh deep sea fish daily at 10.00 am, weather permitting. His advertisements in the Almanac state that he is a ‘Fishmonger &c’, the ‘&c’ being fruit and vegetables, with the addition of game in 1866. In 1880 he advertised that he also took in orders for the Appin Coal Company. The source of his fish supply can only be guessed at but it was presumably one or more of the East Neuk fishing villages, arriving at Dunfermline by train. Thomas Philp was still in business when he died in 1896 at the age of 70. Shortly after his death his widow transferred the business to one William Stiven.

Milk

Perhaps the buying of milk cannot strictly be called ‘shopping’ as it was delivered to the door, with no actual shop involved, but as it is an important food item it is included here. It came from small dairies in the town, which had byres for between six and a dozen cows, and was taken round in the churn on a cart and ladled into the housewife’s own jug. Dairymen rarely advertised but this announcement appeared in the Dunfermline Saturday Press on 23 May 1863.

Perhaps the buying of milk cannot strictly be called ‘shopping’ as it was delivered to the door, with no actual shop involved, but as it is an important food item it is included here. It came from small dairies in the town, which had byres for between six and a dozen cows, and was taken round in the churn on a cart and ladled into the housewife’s own jug. Dairymen rarely advertised but this announcement appeared in the Dunfermline Saturday Press on 23 May 1863.

According to the 1861 Dunfermline Census most of the town’s dairies at that time were kept by women – four out of the five dairy keepers recorded in the Census – with premises in Bruce Street, Knabbie Street, Queen Anne Street, Grieve Street and Beveridgewell. A report in the Dunfermline Press of 31 December 1862 of a meeting of dairy-keepers in Alloa commented that ‘a female, very appropriately we think, was called to the chair.’ The meeting had been called to discuss raising the price of milk, because of a rise in the price of fodder, and the report commented that as not all the town’s dairy-keepers had been present some consumers might find that they were still buying at the old price ‘which, taking into consideration the liberal percentage of water which is usually mixed with it, ought, it is generally believed, to be sufficiently remunerating’. There is no reason, of course, to suppose that the practice of watering-down of milk was confined to Alloa….

By 1867 the number of dairies in Dunfermline seems to have dwindled, according to an article in the Saturday Press of 9 February:

In no town of the same size, we believe, is there a greater scarcity of (milk) than in Dunfermline….Were it not for occasional small supplies obtained from private families who keep their own cows, we believe one half of the town would have to go sometimes without milk altogether. It is quite clear, at least, that the two or three dairies with which the town is blessed, are quite incapable of supplying the ordinary wants of the community with this article of diet. Were one or two enterprising dairymen to take up their abode in Dunfermline they would stand a good chance, we think, of doing a prosperous trade.

It seems that a number of ‘enterprising dairymen’ took up the challenge, as no fewer than eleven of them were recorded in the 1871 census. Four combined dairying with another trade – gardener, mason, iron dresser and smallholder, but the rest were solely devoted to this ‘prosperous trade’.

Bakers

Households in Victorian Dunfermline daily enjoyed a luxury which is now all too rare – freshly-baked bread. According to the 1861 town directory there were seven bakers in the High Street, eleven in other town centre streets and six in the outlying areas. The Census of the same year reveals that these ‘master bakers’ employed between them more than twenty journeymen (bakers who had completed their apprenticeship) and at least twenty apprentices.

Advertisements in the local press mention that as well as bread loaves and rolls, some bakers also made currant loaves, seed, plum and Madeira cake and plain and fancy shortbread. On 21 December 1861 Mrs Shaw, whose shop was in the High Street, three doors west of Guildhall Street, announced that she had added ‘PASTRY in all its branches’ to her repertoire and would provide pastries for Christmas and New Year parties ‘to any extent’. George Philp at the east end of the High Street sold ‘A Variety of FANCY BREAD and BISCUITS and Warm Rolls Every Morning’. David Wylie, in Guildhall Street, supplied ‘Hot Pies and Lemonade at any hour during the day’, and James Muir in Baldridgeburn served Families in the Country free of delivery charges. Thomas Milne’s offer of ‘Oven accommodation given to Families’ reminds us that domestic ovens were not common, at a time when the majority of people lived in just one or two rooms.

The Baking Company

The Company was set up in 1845 with the aim of selling bread at a lower price than was charged by independent bakers. The members were shareholders who contributed to the cost of setting up and running a Company bakehouse and shop and shared the profits at the end of each year in accordance with the amount that each had contributed. The whereabouts of the early premises is not known but by 1855 the Company was operating from a bakehouse in the High Street with a shop next door to it.

It was soon found that lowering prices merely led to a loss of profits and that policy was abandoned, but a dividend continued to be paid to members. By 1863 this system had become unworkable as many members had ceased to buy from the Company’s shop, so in March of that year the Company was re-constituted as a co-operative venture, paying a dividend on every 100 four pound loaves bought, the annual payment to members being higher than to non-members. At the first general meeting of the Co-operative Company in November 1863 the Committee reported that there were 175 shareholder members and that the dividend to members was 3/2d per 100 loaves and to non-members 2/1½ d. By the following May there were 194 members and the dividend had risen to 3/1d to members and 2/7½d to the rest and this steady increase persisted over the following years.

In 1865 there was a suggestion that the Company might amalgamate with the Dunfermline Co-operative Society, but this idea was not adopted. Such was the success of the Company, however, that by 1867 its premises in the High Street, besides being in a bad state of repair, were no longer large enough to meet the demand. New premises were built in South Inglis Street and on 9 November 1867 the Dunfermline Saturday Press announced that the Baking Company would be moving there on the following day.

Some Bakers’ Stories

Most bakers were men, but a few widowed women carried on the businesses of their late husbands. Isabella Shaw gave birth to her youngest child, Alexandrina Davina, at 2 pm on 14 May 1856. At 4.45 pm on the same day her husband Alexander died of bronchitis. The couple had already lost three children in infancy and Alexandrina died of scarlet fever at the age of 11 months, leaving Isabella with four surviving children, Isabella, Janet, Thomas and Mary. Thomas became a lawyer, then an MP and was ultimately honoured with the title of Baron Shaw of Craigmyle. His autobiography describes his mother’s anguish at the death of Isabella in 1860 and her steely determination to give her only surviving son the best education she could afford, to help him make his way in the world.

William Campbell’s bakery at number 6 Abbot Street was opposite the Commercial Bank (whose façade was incorporated into the Dunfermline Museum and Gallery) and in 1854, his daughters Christina and Janet set up a dressmaking and millinery shop next door to the bakery. In 1850, when she was aged about 15, Christina had begun a long courtship with John Beveridge Jnr, the son of John Beveridge who was treasurer to the Commissioners of Police and the Assessor and Collector of the local rates. In 1852 John Beveridge Jnr took up a position in a writer’s office in Glasgow, from where he wrote many affectionate letters to Christina, looking forward to the time when they could be married. On visits to Dunfermline he always met with Christina and in September 1857 he seduced her in the back room of her milliners’ shop. By January 1858 it had become apparent that she was pregnant and a marriage was hastily arranged for the following March but no bridegroom appeared, as he was by then courting a Miss Reid in Glasgow, who he married in December 1859. Christina’s son William was born in September 1858 and John Beveridge refused to pay any maintenance for him. In July 1861 Christina sued him in the Court of Session for arrears of maintenance for William at £8 a year and compensation for breach of promise and loss of reputation. She was awarded £200 by the judge.

The whole matter had caused a major scandal in Dunfermline. Illegitimate births were by no means uncommon in the town, but this one involved respectable inhabitants and the trial was reported at length in the Dunfermline Press and other newspapers. In giving evidence Christina stated that her health during pregnancy had been poor and the birth had been difficult. When her father moved his bakery to the High Street in 1863 he mentioned that Janet would be carrying on the millinery business in Abbot Street so it would seem that Christina was no longer strong enough to help her. She died of TB on 14 June 1864. Her son, William, was still living with his grandfather in 1871 but the old man died in three years later and after that William Jnr, and his aunts Frances and Annie, moved to Glasgow where William found work as an engine fitter and his aunts as shop assistants.

Robert Sanders, whose old-established bakery was in Bridge Street, came from a family that combined farming with baking. His father Robert farmed at St Margaret’s Stone and at Robert Jnr’s baptism in July 1788 the witnesses were John Sanders, baker in Dunfermline, and William Sanders farmer at Easter Pitcorthie. Robert followed the family tradition and as well as running his bakery in Bridge Street he farmed at Masterton, where his first wife, Margaret Wilson, died in April 1827. He was a very successful farmer, winning prizes for cattle and horses in local shows, often in competition with Robert Ebenezer Beveridge of Urquhart farm, who was named in Robert Sanders’ will as one of his executors.

Robert Sanders seems to have been fond of children. When a Miss Ford opened a dame school at Masterton in 1861 it was held in a room that Sanders allowed her rent-free. The school catered for children who were too young to walk as far as Dunfermline to school, and reports of its examination days, which Robert Sanders always attended, are very complimentary to Miss Ford, even though many of her pupils were the children of itinerant ploughmen who might stay in the area for no more than one season. Robert also frequently opened one of his fields for the Sunday School outings of various Dunfermline churches and was entrusted with the keys of the vacant Pitreavie Castle, which he also opened to Sunday School outings.

Confectioners

Some bakers made cakes and biscuits, but for special occasions you turned to a confectioner. James Dingwall, for instance, made Bride’s and Ornamental Cakes to Order and also jellies and creams. There were no flavoured condensed jelly slabs or crystals; jellies had to be made from scratch, using gelatine sheets or granules if they were available. If not, you made your own gelatine by boiling bones and then reducing and clarifying the resulting stock – a laborious operation that required skill to produce a palatable result.

Some bakers made cakes and biscuits, but for special occasions you turned to a confectioner. James Dingwall, for instance, made Bride’s and Ornamental Cakes to Order and also jellies and creams. There were no flavoured condensed jelly slabs or crystals; jellies had to be made from scratch, using gelatine sheets or granules if they were available. If not, you made your own gelatine by boiling bones and then reducing and clarifying the resulting stock – a laborious operation that required skill to produce a palatable result.

John Sanders made Brides and Christening Cakes, Shortbread and Pitcaithly Bannocks, Seed and Plum Cakes, Jellies and Creams, Fancy Biscuits and Tea-Bread. A major difference between bakers and confectioners was that the latter also baked pastry, and at holiday times John Sanders provided Christmas pies and mince pies in addition to the hot pies he baked every evening. He also ran a ‘Commodious Refreshment Room’ at his High Street premises and in 1865 obtained planning permission to excavate a cellar ice house under the street in front of his shop, presumably so that he could add ice-cream to his menu.

John Sanders’ Refreshment Room was the forerunner of the ‘City Restaurant’ that was set up by his son John in 1867 and, having run through three subsequent owners, finally closed a century later in 1967.

John Sanders had trained with Helen Finlayson, who had established her confectioner’s business in 1812, retiring in 1850 to keep house for her widowed brother-in-law Ebenezer Graham, a linen manufacturer. At that point John Sanders took over the business along with James Dingwall, another of Helen Finlayson’s trainees. James Dingwall set up on his own in the High Street in 1853, his wife Jessie Galloway running a servants registry at the same address. James died in 1870 and Jessie carried on the business for a couple of years but in 1873 sold it to Margaret Carmichael, who had set up as confectioner in Bridge Street, after the death of her shipmaster husband Alexander Carmichael at sea in his ship the Dream of Glasgow in 1855.

Before he died Alexander Carmichael had managed to write a will leaving his wife £60 a year for life, out of the interest of a life insurance, a bank account and his share in the Dream. There was also a certain amount of cash left after clearing the ship, and that also went to his wife, so she used the money to set up in business. There is no evidence that she had any experience in confectionery but she employed three men and a boy and her brother, George Templeman, who lived with her, seems to have trained as a confectioner. After buying James Dingwall’s High Street shop, Margaret Carmichael also kept on the one at Bridge Street and she is recorded in directories up to 1878. By 1881, however, she had retired and moved to Glasgow to live with her son Thomas, a chemical manufacturer.

In the 1860s John Sanders, James Dingwall and Margaret Carmichael were the only confectioners in Dunfermline but over the years the numbers rose until by 1893 the Dunfermline Directory listed 16 in and around the town centre. Although the population had increased over those thirty and odd years it had not grown by 500%, so the extra market for luxuries must have been due to the increasing prosperity of a greater number of people in the town.

Conclusion

It is tempting to look back nostalgically to those days of a multitude of small shops, but many of us can still remember the drudgery of traipsing from shop to shop, queuing in most of them then carrying a heavy basket home, and doing it several times a week because of the lack of cold storage. It is sometimes said that shopping in that way meant that people had greater opportunities to socialise, but nowadays, because food shopping can be done once a week under one roof, we have time to meet friends for coffee in a warm, comfortable café or in our own homes instead. For working people, the old way of shopping meant constant juggling of time and energy to get to the shops before they closed in the evening or on a Saturday. Perhaps we have lost something in some ways, but we have gained much in others.