Gardening in Victorian Dunfermline

by Sue Mowat

In July 1854 the Fife Herald published a report on a Dunfermline horticultural show. Among its descriptions of the exhibits and the lists of prize-winners, the report commented that :

The Dunfermline amateur florists are reputed all around this district as being superior in the cultivation of the many-tinted family of flora, and no less so in that of the vegetables and roots, early cabbages and carrots, as well as the pansies and dahlias.

There is plenty of evidence from other contemporary sources that this was no idle boast.

The Horticultural Societies

The Horticultural Societies

By the mid-nineteenth century four horticultural societies flourished in the town, each of them holding at least two competitive shows every year. All the competitors were men and because much of the information in this article comes from newspaper reports of the Societies and their shows, it is inevitably heavily male-biased. Although this no doubt reflects to some extent the actual situation ‘on the ground’ there is no reason to suppose that women had no interest in gardening, although they probably confined themselves to flower cultivation. The cover of Mrs Loudon’s “Gardening for Ladies” published in 1834 shows a lady and her child wielding a rake and a hoe. However daintily they may be grasping the tools there can be no doubt that they intend to use them.

The Ancient Society of Gardeners

Although it was not particularly ancient, having been founded in 1716, this was the oldest of the four Societies. It had two aims. One was to act as a Friendly Society, paying out annuities to members aged over 65 and covering the funeral expenses of those who died. The other was to improve the cultivation of flowers and vegetables. Over the years the second aim fluctuated in importance but in the 1830s the horticultural element was in the ascendant. The Society’s entry in the Dunfermline Register for 1836 advertised the usual quarterly meetings that were held to distribute annuities and transact Society business in general, but added the information that:

At the meeting in April there will be an exhibition of Auriculas, Primroses and Greens. In May of Tulips, Wallflowers and Cabbages. In July of Gooseberries, Pinks, Violets and Carrots.

In the 1860s a broadly similar schedule of shows still continued, although the items for competition had been expanded. In April the classes were for auriculas, polyanthus and/or primroses and the heaviest six leeks (in 1865 this was won by John Reid, a market gardener who was the treasurer of the Society, with a total weight of 10½ lb). The May classes were for tulips, cut flowers, pansies, wallflowers and the heaviest cabbages and rhubarb. In July it was roses, pinks, sweet williams, phloxes, penstemons, stocks, cut flowers from the open border, gooseberries, red and white currants and the heaviest yellow turnips and carrots (size was all-important for competition vegetables in all the horticultural societies).

The lists of prizewinners were short, with the same names regularly recurring, reflecting the comparatively low numbers of actively gardening members. Most of the winners would have raised their own plants, but a few were more likely to have shown the produce of their gardeners. James Alexander Hunt of Pittencrieff, for instance, and the wealthy manufacturers Thomas Alexander and William Matthewson.

The Society’s meetings and shows were held in the Music Hall until 1869, when it transferred to Daniel Lamond’s Hall in South Chapel Street (Randolph Street) and the May meeting was always followed by a dinner for 20 or 30 members in Mr Turnbull’s Commercial Hotel on the north-west corner of Douglas Street and Queen Anne Street. In 1865 came the first of regular annual picnics for members, their friends and families.

Dunfermline Horticultural Society

This society was established on 30 September 1834, probably as a successor to the Dunfermline Florist Society, which had been formed in 1827 for ‘the cultivation and improvement of the best fruits, the most choice sort of flowers and those vegetables which are most useful in the kitchen’.

The Horticultural Society’s entry in the Dunfermline Register for 1836 named Dr Dewar as its president, James Smith Ronaldson (writer) and George Birrell (manufacturer) as vice presidents, Charles Macara (chemist and nurseryman) as treasurer and Thomas Stevenson (writer) as secretary. Its aim was:

To encourage attention to Horticultural science by giving premiums to those who may produce the best and most rare articles. Funds for this purpose are raised by Donations and by an Annual Subscription of 2s 6d from the members.

There will be two Exhibitions this year in the Mason’s Hall, Reform Street; the first on the second Tuesday of July; and the second on the third Tuesday of September. These will be open to the Public from One till Five o’clock p.m. Members of the Society and those who pay One Shilling will be admitted by Tickets during the first two hours; and those who Pay Sixpence each, thereafter, until the Exhibition is closed.

In the prestige of its officers the Horticultural Society was second only to the Ancient Society of Gardeners. Presidents and Vice Presidents during the four decades or so of its existence included Lord Elgin and members of his family, members of the Hunt family of Pittencrieff, Mr Wellwood of Garvock, Mr Stenhouse of South Fod, Sir Peter Halket of Pitfirrane, other local landed gentry and a succession of prominent Dunfermline citizens. Its shows were important social occasions, press reports invariably beginning with a list of the local great and good who were in attendance.

During the early years competitors came from far and wide. In 1836, for instance, prize-winners included gardeners from Dalmeny, Riccarton and Craigiehall and nearer home from Fordel, Torry, Pitfirrane and Valleyfield. The early shows were also divided into two sections – professional gardeners and a smaller list of classes for ‘cottagers’ who competed for prizes for pinks, roses, violets and potatoes.

In 1845 the Northern Warder reported that the Society had not held any exhibitions since 1842, but by 1847 it was up and running again, with two exhibitions held in the Free Abbey School. The Fife Herald report on the September show particularly mentioned a bouquet entered by James Drysdale, Baldridgeburn, composed of dahlias and other flowers, in the shape of an elegant vase 8 or 10 feet high. In the fruit section there were prizes for pineapples, grapes, peaches, nectarines, apricots, red currants and gooseberries. Vegetables (heaviest, of course) turnips, onions and potatoes. The flower section included China roses, verbenas, hollyhocks, stocks, China asters and fuchsias. The Dunfermline band played in the school playground and after the show ‘a goodly company of the members’ had dinner in the Spire Hotel, annual dinners being a feature of all the town’s horticultural societies.

The July show in 1849 was still divided into two classes, professionals and cottagers, but the cottagers section now included a far wider selection of items – pinks, pansies, stocks and ranunculus, all of different varieties, hardy annuals, China roses and others of different varieties, strawberries, turnips, peas, carrots and early cabbage. Supplementing the regular classes were ‘additional premiums’, single prizes donated for specific items. In this case William Hunt Jnr. of Pittencrieff gave a prize for the heaviest two early cabbages, Robert Thomson, draper in Bridge Street, for the best six moss roses and William Brown druggist (chemist) for the best six ranunculus.

As well as submitting plants for competition, local gardeners exhibited their finest efforts and at this show the star attraction came from Erskine Beveridge who contributed ‘some of the rarest and finest plants displayed, amongst which there was a very fine specimen of the butterfly plant, the flower of which appears as a large, well-formed butterfly perched on a long leafless stalk’ (this was probably Oncidium papilio, the butterfly orchid). By 1859 another competition section had been added to those for professional or ‘practical’ gardeners and cottagers – the amateurs section. This category is difficult to define but it seems to encompass well-off individuals who were also keen gardeners, although some of them were doubtless helped by their gardening servants. At the September show the amateur prizewinners were James Bruce (grocer and wine merchant), Richard Moffat (Inverkeithing baillie), Thomas Alexander (a manufacturer whose coachman was also his gardener), John Carr (manager of the Bank of Scotland, Dunfermline), Thomas H Tuckett (Roads Surveyor for West Fife, who also employed a gardener) and George Tweedie (possibly from Blairadam).

As well as submitting plants for competition, local gardeners exhibited their finest efforts and at this show the star attraction came from Erskine Beveridge who contributed ‘some of the rarest and finest plants displayed, amongst which there was a very fine specimen of the butterfly plant, the flower of which appears as a large, well-formed butterfly perched on a long leafless stalk’ (this was probably Oncidium papilio, the butterfly orchid). By 1859 another competition section had been added to those for professional or ‘practical’ gardeners and cottagers – the amateurs section. This category is difficult to define but it seems to encompass well-off individuals who were also keen gardeners, although some of them were doubtless helped by their gardening servants. At the September show the amateur prizewinners were James Bruce (grocer and wine merchant), Richard Moffat (Inverkeithing baillie), Thomas Alexander (a manufacturer whose coachman was also his gardener), John Carr (manager of the Bank of Scotland, Dunfermline), Thomas H Tuckett (Roads Surveyor for West Fife, who also employed a gardener) and George Tweedie (possibly from Blairadam).

The Society always needed a large hall for its shows and in 1854 the Music Hall had become its regular venue. The annual subscription was still 2/6d and there were still two shows every year, in July and September. New items for competition were added to the programme, as in September 1861 when –

A somewhat new feature in the show, namely the competition of turnips grown in the open field, attracted considerable attention. The specimens shown were of a truly gigantic nature and were much admired.

A year later the Dunfermline Press reported that:

For some years the taste for greenhouse and variegated plants has been increasing rapidly and steadily. This year the Society offered an additional stimulus to this taste, by offering several prizes for the best varieties. Hitherto these plants had been seen at our shows only on the exhibition tables, displayed as great curiosities. Yesterday no prizes excited a keener competition, while, notwithstanding the large number thus brought forward, the display on the exhibition table was in no degree diminished.

The prize for the best 12 variegated plants in pots was won by Alexander Stenhouse, head gardener at Pitfirrane. Erskine Beveridge’s gardener, Alexander Robertson, won a first for the best collection of variegated plants. Mr Robertson had always been noted for his variegated plants and exotic ferns and in the previous year he had combined the two elements by exhibiting a variegated fern, Pteris Argyrea.

The prize for the best 12 variegated plants in pots was won by Alexander Stenhouse, head gardener at Pitfirrane. Erskine Beveridge’s gardener, Alexander Robertson, won a first for the best collection of variegated plants. Mr Robertson had always been noted for his variegated plants and exotic ferns and in the previous year he had combined the two elements by exhibiting a variegated fern, Pteris Argyrea.

It was not only plants that were on exhibition:

Mr Bruce (grocer) Queen Anne Street exhibited a very fine vase of West India pickles. The violinists on the platform were very nearly obscured by a collection of beautiful vases, statuettes &c &c contributed by Messrs Wilson, Lochhead Pottery; while underneath, ranged along the front of the platform we observed a very fine and extensive collection of photographs, stereoscopic views &c &c sent in by Mr Alexander Taylor, Kirkgate.

In the 1870s, the Society introduced a show in early June which concentrated mainly on tulips but by 1880 it seems to have been running out of steam and that October a meeting was held in St Margaret’s Hall to discuss the formation of a new Society. Provost James Walls was asked to make a few remarks and he reflected on the progress of horticulture in the district:

A great deal had been done of late years in favour of cottage gardening and in the way of inducing men to spend their time in beautifying their grounds instead of in a worse place. It was almost two centuries since a Horticultural Society was started in Dunfermline (The Ancient Society of Gardeners)….That Society had fallen very much from its original height and instead of giving a large number of prizes for excellence, as it did then, it was only looked upon now as a Benefit Society….He remembered that about forty years ago a Horticultural Society was started in Dunfermline and it was a very flourishing one for a number of years, but somehow or other it fell away.

It was decided that a new society would be formed with two classes of competitors, gardeners and amateurs and only one exhibition a year, on a Friday and Saturday in August. The annual subscription would be 2/6d and there would be a prize fund. The name of the Society would be The Dunfermline and West of Fife Horticultural Society but competitions would be open to anyone from any place in Scotland – it was remembered that in the early days of the Horticultural Society competitors had come from Dalmeny and Hopetoun. The first President of the new Society was Lord Elgin and the list of sixteen Vice Presidents was headed by H Campbell Bannerman MP and included most of the local landed gentry and the Provost. The committee comprised 21 professional Dunfermline residents. (Quite why such a superfluity of Vice Presidents was needed is not clear – perhaps they were to hold office in rotation.) The new Society continued in this form until 1904, when it amalgamated with the Dunfermline Chrysanthemum Society under the auspices of the Carnegie Trust.

The Cottagers

In his “Reminiscences of Dunfermline” Alexander Stewart, recalling his childhood in the 1830s and 1840s, wrote at length about the weavers of his day, including their fondness for gardening:

Sometimes they would pay a visit to their little gardens, to see and to smell their beds of pretty flowers. There was then, as there is now, great competition among them as to who could rear the most perfect specimens of vegetables and flowers. Some of the tulip and dahlia beds were unmatched anywhere.

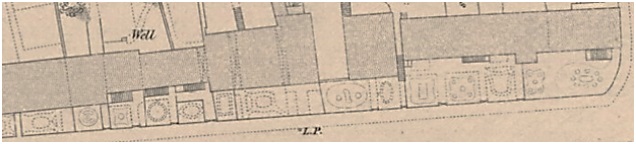

The layouts of some of the ornamental gardens of these amateur florists (a florist at that time was a flower-grower, not a flower-seller) are shown on the 1854 Ordnance Survey plan of Dunfermline, like these in Netherton Broad Street:

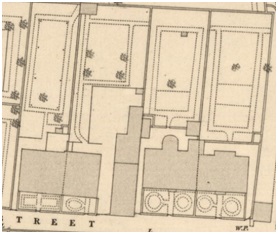

The utilitarian vegetables and fruit would have been grown in the back gardens in neat rows. The riotous ‘cottage garden’ of our fantasies had no place in mid-nineteenth century Dunfermline – for both ornament and utility, neatness and formality were all-important, as is evident in the Buchanan Street section of the 1854 plan.

Some of the owners of the Netherton and Buchanan Street plots would have belonged to the Southern District Horticultural Society, whose members lived in the area to the south of the High Street. This Society had been formed in 1848 specifically for cottagers – no professionals or amateurs competed in its shows, although some of its more experienced members exhibited with the Dunfermline Horticultural Society.

The Southern Society specialised in tulips, so it held three shows every year in the Rolland Street School, one for tulips, pansies and wallflowers at the end of May or beginning of June and the other two in the usual months of July and September. The early show inevitably included a ‘heaviest’ class, this time for three stalks of rhubarb. The list of prizes paid for by the Society was usually fairly short – between eight and sixteen, but there was always a much longer list of ‘extra prizes’ that had been contributed by various individuals for specific kinds of plant.

The extra prizes at the tulip show named the kinds of tulips being grown. Plain ‘breeder’ tulips were pure white or yellow but could also be flamed, with a contrasting colour starting at the centre of each petal and rising up to the edge, or feathered, with the contrasting colour on the petal edges only. ‘Rose’ tulips had rose-coloured markings on a white ground, in ‘bizarre’ tulips the ground colour was yellow and ‘bybloemen’ varieties had purple markings on a white ground. These varieties are now known as ‘English florists’ tulips but are seldom available for sale today as they do not make such good garden plants as the more modern kinds. The illustration on the right is of a bybloemen tulip.

The extra prizes at the tulip show named the kinds of tulips being grown. Plain ‘breeder’ tulips were pure white or yellow but could also be flamed, with a contrasting colour starting at the centre of each petal and rising up to the edge, or feathered, with the contrasting colour on the petal edges only. ‘Rose’ tulips had rose-coloured markings on a white ground, in ‘bizarre’ tulips the ground colour was yellow and ‘bybloemen’ varieties had purple markings on a white ground. These varieties are now known as ‘English florists’ tulips but are seldom available for sale today as they do not make such good garden plants as the more modern kinds. The illustration on the right is of a bybloemen tulip.

In the 1860s the Southern Society had around 60 members and during that decade just over 50 of them were prize winners. Some only appeared once in the prize lists and others were winners at practically every show, the Hoggan and Meldrum families being particularly well-represented, especially Andrew Hoggan, a power loom tenter at the St Leonard’s Works, who lived in Bothwell Street and then moved to 32 Edgar Street. One of the stars, however, was Alexander Hutton, a mason who lived in Moodie Street. He owned a greenhouse and specialised in fuchsias, geraniums, tender ferns and agapanthus which he entered for both exhibition and competition and he also grew tulips, hollyhocks, phloxes and lilies. Hutton exhibited at the Dunfermline Horticultural Society’s shows and in 1862 was elected to their committee.

Another outstanding member was Daniel Toshack, a weaver who lived in the Hospital Hill Toll House. He was a frequent prize-winner for potatoes, carrots, onions, delphiniums, sweet williams, African and French marigolds, asters, tender flower in a pot, pinks, foxgloves, phlox, twilled asters, lobelias, penstemons and pansies. In 1861 he gained the most prizes of any member, and was also Treasurer of the Society. He died in 1882 at the age of 74 and his grave is marked by a broken flat stone next to a tree on the east side of the path from the Maygate to the north porch of the Old Nave.

John Ferguson, who was president of the Society in 1860 and 1861, was another frequent prize winner. He was a damask weaver who lived in Netherton Broad Street and was a member of the Dunfermline Horticultural Society committee in 1861 and 1865. On several occasions he was a prizewinner in the Cottagers section of its shows. He also acted as a judge at the shows of the Northern Society in 1861 and 1862. By 1881 he had given up weaving to work as a jobbing gardener and was still working when he died of a cerebral haemorrhage in 1887 at the age of 70.

Adam Cooper, a bleacher who lived in Elgin Street and almost certainly worked at Ralph Walker’s bleachworks by the bridge over the Lyne Burn, was not a spectacular prize winner but gets a mention because he died aged 55 of a heart attack in August 1880 while ‘engaged in watering his flowers a little after six o’clock in the morning’.

The Northern District Horticultural Society

There is no definite information about the date on which this Society was founded, but it may have originated as the Pittencrieff Horticultural Society, which was announced in the Dunfermline Register for 1838. The object of the Society was ‘to promote a systematic mode of cultivating Vegetable Produce, neatness in laying out their Gardens and frequent intercourse amongst the Members’. The President was David Lindsay, a former RN seaman and native of Falkland who returned home to become a park keeper, and the Treasurer and Secretary was John Reid (more about him later). In 1842 the President was James Dickie, a weaver who employed three men. All three of these early members lived in James Place, the part of Pittencrieff Street west of William Street.

In September 1852 the Fife Herald reported on the show of ‘the amateur florists and vegetarians of the west end of Dunfermline’ held in ‘Mr Brand’s school, Golfdrum’. From 1859 until July 1865 the Dunfermline Press carried regular items about the shows of the Northern Horticultural Society, held in the Maclean School at the head of Buffies Brae, but after that year nothing more is heard of it. Like its Southern counterpart, the membership of the Northern Society were all cottagers but it only held two shows in the year, in July and September. As with the Southern Society, the number of Society prizes was heavily outweighed by the list of Extra prizes.

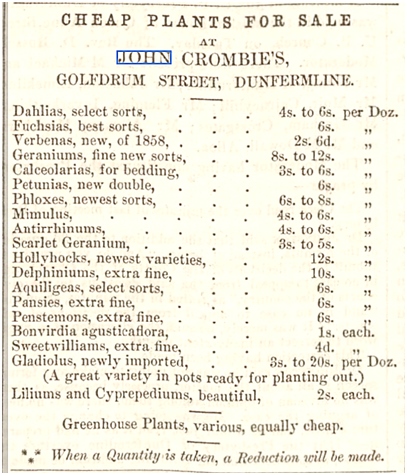

One member who did not compete but who usually provided items for exhibition and sometimes acted as a judge was John Crombie of Golfdrum. The 1841 and 1851 Census returns list him as a weaver and those for 1861 to 1891 as a grocer but that is not the whole story. Behind his house at 83 Golfdrum Street there were a hot house, a greenhouse and a range of cold frames in which he grew a variety of plants some of which were rare at the time, like the aubergine and the cotton plant that he exhibited at the 1852 show. In 1859 he showed ‘a great number of rare exotics’. John Crombie also exhibited at the Dunfermline Horticultural Society shows. In July 1861, for instance, lilies, cacti, gloxinias, ‘a fine stand of verbenas and begonias’, fuchsias, petunias, phloxes, cannas and geraniums. In the September he contributed veronicas, variegated begonias, cestrum aurantiacum, phloxes both cut and in pots, calceolaria and a canna Warsewga. He also grew more everyday plants for sale and his advertisement in the Dunfermline Press in April 1860 is typical:

In 1862 John Crombie offered a large assortment of greenhouse plants and also greenhouses, fully stocked with plants if required. In 1865 he seems to have retired because that year he sold a 28-foot greenhouse and a 17-foot cold frame. (It may be no co-incidence that this is the year when the Northern Society disappeared from the local press.) One more important event in John Crombie’s personal life came in November 1869, when his only child, Janet, married Gilbert Rae, the founder of the Golfdrum Aereated Water Works.

Market Gardeners

Market Gardeners

The market gardening tradition in mid-nineteenth century Dunfermline stretched back at least 150 years. John Deal, who had been one of the founder members of the Ancient Society of Gardeners in 1716, when he was head gardener at Pittencrieff House, ran a market garden in a large area to the south of East Port Street which was still called ‘Deall’s Yeard’ on the plan of the town made in 1771. It is still mostly an open space and now comprises the Walmer Drive car park. The author of the series of Dunfermline reminiscences called “When We Were Boys” wrote about a market garden in the Netherton run by Robert Inglis, which he had known in his childhood.

The site now occupied by Messrs Mathewson’s extensive works was partly a large market garden and a portion in Elgin Street down to the burn-side was partly grazing ground and partly small allotments. The market ground there supplied many of the families in the south side of the town with vegetables and fruit – the early potatoes were sold by the ‘lippie’ or the stone and were weighed in a little office near the gate. The berries were measured out in tins by the pint and the quart. The boys and girls liked to go for the provisions and to get the run of the big garden with its long walks with their boxwood borders. The great time for us was when the early potatoes were ready for digging and the berries and apples and pears were ripe.

The site of Inglis’ market garden was shown on the 1854 Ordnance Survey plan of Dunfermline (on the left). The ‘extensive works’ mentioned in When We Were Boys was a power loom factory built in 1864 which was second in size only to Erskine Beveridge’s works at St Leonards. The gardener Robert Inglis was a former farm worker who lived at Milton Green and leased his market garden from Lord Elgin. When the garden land was sold for the factory to be built, Robert Inglis established a dairy at Milton green which he ran until his death in 1881. The site of his former garden is now covered largely by army offices and a Fife Council Environmental Services depot.

The site of Inglis’ market garden was shown on the 1854 Ordnance Survey plan of Dunfermline (on the left). The ‘extensive works’ mentioned in When We Were Boys was a power loom factory built in 1864 which was second in size only to Erskine Beveridge’s works at St Leonards. The gardener Robert Inglis was a former farm worker who lived at Milton Green and leased his market garden from Lord Elgin. When the garden land was sold for the factory to be built, Robert Inglis established a dairy at Milton green which he ran until his death in 1881. The site of his former garden is now covered largely by army offices and a Fife Council Environmental Services depot.

Another market gardener who originated in the Netherton was William Ferguson, who was living there in 1841. By 1851 he had established a market garden at Brucefield Feus. In November 1860 he advertised a sale of ‘A LARGE and Select Collection of ROSES, (several hundred varieties) FRUIT TREES, GOOSEBERRY BUSHES, BULBOUS ROOTS, HERBACEOUS PLANTS &c &c’, all of which was in preparation for a move to Burntisland, where he ran a successful business at James Park for many years. He did not sever all ties with Dunfermline, however. He exhibited at various Horticultural Shows and seems to have also maintained some ground at Brucefield, which had been taken over by his son James by 1881.

The Dunfermline market gardener par excellence, however, was John Reid of James Place, who joined the Ancient Society of Gardeners in 1825 as a young man of 20. He was elected Deacon of the Society in 1831 and Treasurer in 1845, a post which he held for many years afterwards. His garden lay on a gentle slope to the south of James Place. The 1841 Census (by which time he was married and had five children) calls him a ‘gardener and hand loom weaver’ but by 1851 he was firmly established as a ‘gardener’. The 1855 Valuation roll reveals that he was the owner and occupier of his house, byre and garden with a rental value of £21 and that he also owned several houses and loom stances in James Place.

John Reid was a frequent prize winner at Horticultural Society shows, with auriculas, polyanthus, primroses, tulips, pansies, wallflowers, roses, pinks, antirrhinums, sweet williams, stocks, phloxes, dahlias, penstemons, rhubarb, apples, red and white currants, leeks, turnips, cabbages, red cabbage, Savoys, peas, beetroot, swedes, onions and carrots. At the Dunfermline Horticultural shows he exhibited pinks, gladioli and berries and won numerous prizes. He also acted as a judge at the shows of the other Horticultural Societies in the town and elsewhere. The list of his prizewinning flowers and vegetables indicates the kinds of items that he sold and it is noticeable that he did not go in for exotic or unusual plants either as exhibits or for competition, concentrating instead on varieties that were readily saleable. His eldest son, John Reid jnr moved to London as a young man, as a partner in the firm of Melles, Jones, Reid & Co, manufacturing and importing artificial flowers, feathers, ribbons and various ornaments for hats, bonnets and other feminine adornments. The firm flourished and in February 1880 John jnr bought the Saline estate of Dunduff for £8500. And who better to lay out the grounds at his new estate than his father? In the following August the Ancient Society of Gardeners:

….were kindly invited by Mr John Reid snr to visit Dunduff and inspect the improvements in progress there, which are transferring to this rather “stern and wild” locality some of the brilliant hues of a finer cultivation; giving warmth and light and contrast to the sombre tints of the bracken and bluebell by a series of beautiful groups of many flowers, comprising roses, lilies, pansies etc….an inspection of the house was made and the party then adjourned to the open air – to see how the grounds were laid out and the flower beds and fern clumps arranged. Then a descent upon the gooseberries was made, after which the party were marshalled for a walk to Hillhead farmhouse – Mr Reid describing all the improvements as he led the way.

Although he and his family often holidayed at Dunduff, John Reid jnr continued to be based in London and seems to have left the day to day running of his estate to his father. When John snr died of bronchitis in 1890 he was described on his death certificate as ‘estate factor’. All his property in James Place was bought by John Warwick, the head gardener at Pittencrieff House who continued to run the market garden until his death in December 1911, from a heart attack in Muir Bros music shop in Chalmers Street.

Shopping For The Garden

The requirements of gardeners are universal and timeless – everyone needs seeds, plants and tools – so where did the Victorian Dunfermline gardener buy these things? We have seen that plants of all kinds could be bought from market gardeners and ‘florists’ but there was at least one other option. The auctioneer William Clark jnr (builder and owner of the Music Hall) regularly advertised auctions of ‘Dutch Flower Roots’ (ie bulbs). A typical advert appeared in the Dunfermline Press in October 1836, announcing that Clark had received a large case of bulbs from ‘that eminent Grower Leonard Roozen, near Haarlem, Holland’ containing double and single hyacinths, narcissus, tulips, crocuses, snowdrops ‘and a variety of other Bulbous Roots’. In the following February there was an auction of Dutch double and single anemones, Turkish and Persian Ranunculus, Gladioli and Ferraria (probably Ferraria ‘crispa’, the Starfish Lily). In October 1865 another auctioneer, Robert Dodds, was selling single and double hyacinths, polyanthus, single and double narcissus, tulips, crocuses, Crown Imperials, persica fritillaries, jonquils, colchicum, scillas and arums. Some people obviously bought by mail-order, otherwise Edward Sang and Sons and James Tough, nursery gardeners and seedsmen in Kirkcaldy would not have bothered to advertise in the Dunfermline Press.

Seeds seem to have mainly been sold by the local druggists (chemists) who regularly advertised both garden and agricultural seed, although they seem to have concentrated more on the latter judging by the number of varieties of turnip seed they stocked. Alexander Taylor, the grocer/photographer in the Kirkgate sold garden seed and would provide a catalogue on request. One of the druggists, David Anderson at the west end of Bridge Street, also sold bulbs – his hyacinths cost 6s a dozen.

James Bonnar at the Cross, that purveyor of all things metal, sold cast-steel spades, rakes, hoes, reels and lines ‘from the Best Makers at the most Moderate Prices’. James Stewart’s Ironmongery, Grocery and Seed Warehouse at 20 High Street, stocked Black’s cast-steel garden and flower spades and shovels and garden reels, rakes, lines and hoes. James Bonnar also sold garden seats and chairs and something called the ‘Aerial Chair’ which could be seen in operation at his shop and was possibly for use outdoors. No-one advertised flower pots but they were presumably available from the various brick and clay works near the town.

To Be Continued

When I started researching this article I did not realise what a massive project it was going to be. The account you have just read only skims the surface of some of the more public aspects of the subject and a few of the people involved. My next effort will be based on a series of articles published monthly in the Fife Herald from 1870 to about 1875 that were specifically aimed at cottage gardeners in Fife and contained detailed instructions on various topics and a ‘work of the month’ section that reflects local practices and conditions in a way that general gardening books cannot.